To Reach the Clouds (24 page)

Read To Reach the Clouds Online

Authors: Philippe Petit

Shall I tell the truth? I send Annie back to France. I don't want anything to dull the splendor of my newfound fame, to slow the unrestrained and joyous tempo of my new beginning.

America has saluted me.

New York City adopts me.

I stay.

I discover the city by myself, impatiently.

I incessantly defend against cops and vagrants my new street-juggling territories: Sheridan Square in the Village at night, Washington Square Park by day.

Jim Moore welcomes me as a roommate in his airy, well-lit loft on Hudson Street, a cable-tow's length from my cherished twin towers. There, years later, my friend the painter Elaine Fasula creates a masterpiece: we rejoice in the home birth of our daughter, Cordia-Gypsy.

Â

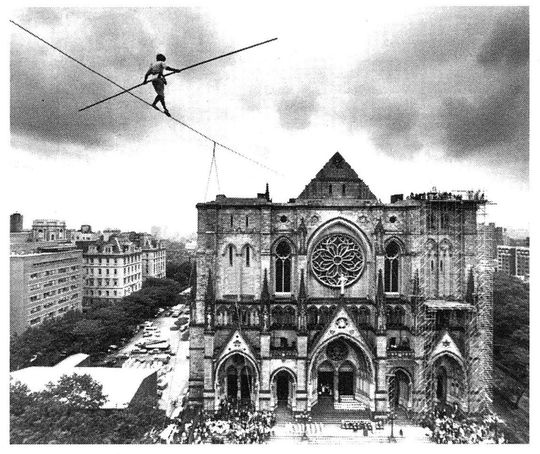

Looking for more marvels, I stumble upon an unfinished Gothic cathedral uptown and fall in love. Following a surprise walk high above the nave for a few friends, I bring the facade of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine to the attention of maillions by walking across Amsterdam Avenue from a sixteen-story building to the base of the yet-to-be-built north tower. I come bearing to the bishop and the dean the golden trowel that was used in 1892 to cement the cathedral's first stone. “Following a forty-year hiatus, the cathedral builds again!” announces the caption under a large photograph gracing the front page of

The New York Times

on September 30, 1982.

The New York Times

on September 30, 1982.

I become an Artist-In-Residence at the cathedral, which provides an office and shelters my equipment and archives. I continue to offer my art to the church, staging performances inside and outside, raising funds for, and awareness of, its numerous programs. Traveling around the world, I become something of an ambassador of St. John the Divine. And twice a yearâit's become a traditionâI play maintenance man and change the 150 bulbs of the chandeliers of Synod Hall, where my practice wire is invisibly set between balconies.

Â

The red PROJECTS box has emigrated from rue Laplace to St. John the Divine. It sleeps with my archives, protected from the agitation of the world by three feet of granite.

One day, I slide my hand into the box and retrieve a forgotten file on canyons. Several journeys to Arizona, numerous meetings with my brothers the Navajo Indians, and the work-in-progress

Canyon Walk

is born. It is an opera performed on a high wire

rigged from one rim of the Little Colorado River Gorge (an overlooked gem of the Navajo Nation) to a solitary monolith standing 1,600 feet tall, 1,200 feet away.

Canyon Walk

is born. It is an opera performed on a high wire

rigged from one rim of the Little Colorado River Gorge (an overlooked gem of the Navajo Nation) to a solitary monolith standing 1,600 feet tall, 1,200 feet away.

I will walk from civilization to the unknown. But when? Following seasons of study and preparation, I call without shame: Where are you, patron of the arts, visionary angel? Produce this mythic voyage that will inspire the world!

Â

Oh! Did I forget to mention?

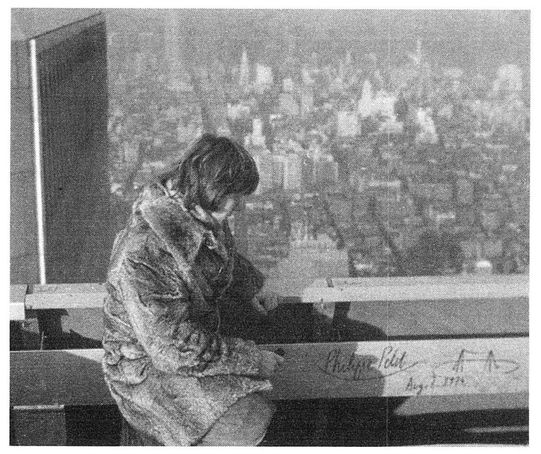

Following my performance between the towers, I am invited to sign the beam on the rooftop of the south tower, the place where the wire and I departed.

I sign in indelible ink, so that the inscription may remain indefinitely.

Â

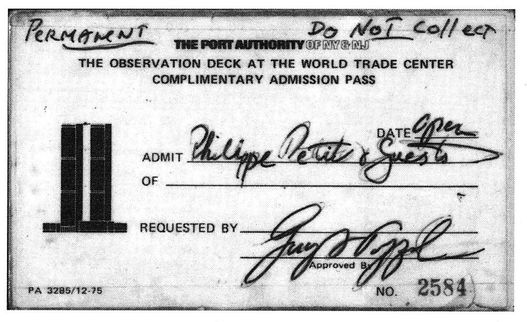

Guy Tozzoli, the thought-provoking, admirable knight of the World Trade Center project, who is responsible for planning,

building, and operating WTC, invites me to his office in the clouds; he congratulates me, lets me know that it was his idea that the judge drop the charges in exchange for a performance, and presents me with a VIP pass to the Observation Deckâ“Valid forever.”

building, and operating WTC, invites me to his office in the clouds; he congratulates me, lets me know that it was his idea that the judge drop the charges in exchange for a performance, and presents me with a VIP pass to the Observation Deckâ“Valid forever.”

I go there quite often. I present my towers to my friends, my family. I daydream one more time â¦

Alone, I lean on the fence, facing the other tower, and try to let the walks come back to mind. They never do. The feat was impossible: I have to make an effort of imagination to set the images in motion.

I am the only visitor who ever looks up. I interrogate the sky with the hope of seeing the bird ⦠but the bird never returns. He is probably uninterested in seeing me with two feet squarely planted on a slab of concrete, albeit a slab floating in reach of the clouds. Yet I'll keep visiting and dreaming forever, atop my inde- - structible twin towers.

Forever, or so I think.

Twenty-seven years later, instead of gathering memories, I relived the World Trade Center adventure. I became once again the eighteen-year-old, the twenty-four-year-old, forgetting to eat, losing sleep, being frightened or elated, laughing at myself.

Â

I shaped the story with thoughts from my month with Marlon Brando during the filming of his workshop “Lying for a Living”âbetween takes, I was furiously scribbling my first draft in red ink. This terribly talented master of deceit taught me golden rules I had forgotten I knew, which applied as much to the page as to the stage. By practicing the discipline of self-imposed intellectual immobilityâakin to the

respect of stillness

Marlon calls forâI was able to apprehend the essence of each chapter before I drafted it. My pen learned to perceive what lurked on the other side of the action it was busy describing until, like him, I could declare, I

can see a smile in the dark.

respect of stillness

Marlon calls forâI was able to apprehend the essence of each chapter before I drafted it. My pen learned to perceive what lurked on the other side of the action it was busy describing until, like him, I could declare, I

can see a smile in the dark.

Â

Later, I pinned in front of me “Lessons of Darkness,” Werner Herzog's “Minnesota Declaration: Truth and Fact in Documentary Cinema.” The single-page text exhorted me to express the “ecstatic truth” about WTC, which is “mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only by ⦔

Â

Then I wrote, listening to another “WTC”âBach's

Well-Tempered Clavier,

the definitive interpretation by Evelyne Crochet at the piano. Her determination and intensity as she starts the second prelude are the determination and intensity of my first steps. Playing the sixteenth prelude, she masters suspension,

like me during my first crossingâin perfect balance, yet vulnerable, alone, and courageous.

Well-Tempered Clavier,

the definitive interpretation by Evelyne Crochet at the piano. Her determination and intensity as she starts the second prelude are the determination and intensity of my first steps. Playing the sixteenth prelude, she masters suspension,

like me during my first crossingâin perfect balance, yet vulnerable, alone, and courageous.

I listened to the two booksâeach of twenty-four preludes and twenty-four fuguesâas twin towers. Her monumental recording reflects my encounters with the gods during the eight crossings on the wire. The music inspired me to invent a fundamental rhythm, to compose faithful suites of words instead of suites of faithful words.

Â

As the words filled the pages, I resisted the urge to punctuate the manuscript's progress with joyful returns to street-juggling and high wire escapades. Each day, I looked at the barn I have been building with the methods and tools of eighteenth-century timber framers. I was tempted to start assembling the last two windows and doors. Butâ

the book, the book, the book â¦

the book, the book, the book â¦

Of course, without permission, wire walking, juggling, and my usual collection of cherished activities flitted around the manuscript, alighted in the margins, and stared at me, the writer, like newborn birds awaiting the return of a parent, and their silent ruckus imprinted the text as much as the ink from my calligraphy pen.

Â

Suddenly, I stopped writing. My towers were under attack, then destroyed, taking an immense number of lives down with them. Then my cathedral was on fire. Doom. Tempest. Chaos. Reflection. After a while, with rebellion in my blood, I wrote, “As an artist, my mission is to create,” and went back to writing.

Above it all, sweeping by when I least expected itâAh, the wind ⦠always the wind!âsoothing my struggles, celebrating my achievements, or warmly teasing or simply smiling at me, was the ethereal presence of a little Gypsy girl who flew away from Planet Earth at the age of nine and a half, without warning or regret.

Rest in Peace, Cordia-Gypsy, in the columbarium of the Cathedral St. John the Divine. The recent fire did not scatter your ashes to the four windsâyou are here encouraging me to keep writing.

With this book, fly with me.

Between paragraphs, I often thought,

The wire is always ready to kill me by surprise, every step of the way

âdid you know that, my little Gypsy? Yet I continued to write as I continue to walk, molding my faith in advance of each step.

The wire is always ready to kill me by surprise, every step of the way

âdid you know that, my little Gypsy? Yet I continued to write as I continue to walk, molding my faith in advance of each step.

Â

Whenever I tackled the impossible and the miraculous of the World Trade Center adventure, I remembered the magician Rene Lavandâdid I ever tell you?âhe had only one arm. Poet and extraordinary card manipulator, he baffled fellow illusionists by concluding his brilliant demonstrations with, “What I just showed you can also be done with two hands!”

Â

Whenever I chewed on my pen, lost, desperate for words, it was the contradictions of a life too full I was reading on the ceiling. Tell me, am I wrong to mock vertigo from summit to abyss, to reveal the world as I see it? To scribe my destiny boustrophedon, from left to right then right to left, like the ox pulling the plough in successive furrows? Line after line, I weave my life, I write this book. It knots and breaks, it splices and tightens.

Â

The book is finished. Craving the caress of many more welltensioned bridges-for-one-day, my soles will resume linking people and places. I have not quit setting cables without permission. I am not yet done with narrow-minded engineers, key-collectors unwilling to unlock doors. I sharpen my rigging knife and, defying gravity, go in search of more sublime, soaring surprises â¦

Â

The child of the trees I was, the skyscraper I became, still wants to

conquer

the worldâ

explore,

I should sayâconvinced that the world inside you, inside me, inside those around us is equally rich in marvels and mysteries. So if the devil calls, tell him I'm already at work on my next book,

The Art of the Pickpocket.

And if he shows up, I'll shout this old African proverb that always made you giggle: “Devil, if you enter my house, I will crush your toes!”

conquer

the worldâ

explore,

I should sayâconvinced that the world inside you, inside me, inside those around us is equally rich in marvels and mysteries. So if the devil calls, tell him I'm already at work on my next book,

The Art of the Pickpocket.

And if he shows up, I'll shout this old African proverb that always made you giggle: “Devil, if you enter my house, I will crush your toes!”

Â

You know the day I soar to meet you, Gypsy, they may say of me, “He learned to walk in mid-air.”

Â

Aerially yours, that's how I wrote this book.

Philippe Petit

The Catskills

March 7,2002

The Catskills

March 7,2002

Other books

Love's Fortune by Laura Frantz

Rogue (Dead Man's Ink #2) by Callie Hart

The Adventures of Sir Gawain the True by Gerald Morris

Mafia Princess by Merico, Marisa

Jan of the Jungle by Otis Adelbert Kline

Alta by Mercedes Lackey

Azrael's Light [Demon Runners of Unearth] (Siren Publishing Classic) by Amy J. Hawthorn

Lives of Magic (Seven Wanderers Trilogy) by Lucy Leiderman

Nan-Core by Mahokaru Numata

Ventriloquists by David Mathew