Tolstoy (47 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

17. Tolstoy and Sonya, August 1895. Their youngest son Vanechka had died six months earlier, so they were still in mourning.

18. The Tolstoy children with their mother in Gaspra, Crimea, 1902. From left to right: Ilya, Andrey, Tanya, Lev, Sonya, Misha, Masha, Sergey, Alexandra. Tolstoy came close to dying during a long period of illness which started in 1901, after he was excommunicated. Despite his hatred of luxury, he accepted an invitation to spend the winter at a palatial villa in the more temperate climate ofthe Crimea. Members ofhis close family all came to visit, thinking they would be paying their last respects. In 1902, the Tolstoys' eldest child Sergey was nearly forty, while their youngest, Alexandra, was eighteen.

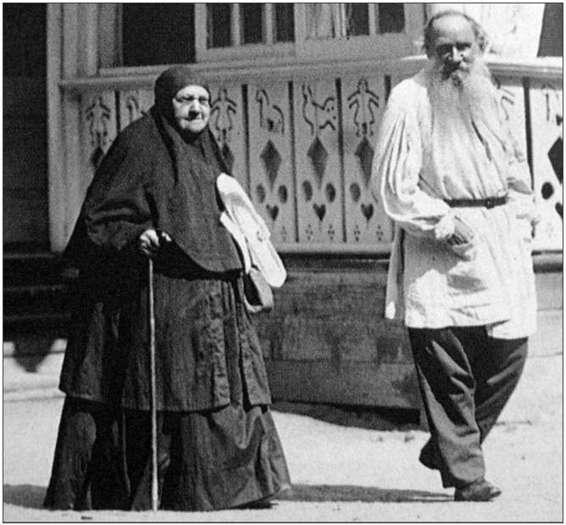

19. Tolstoy and his sister Maria (Masha), 1908. Despite the fact that his sister became a nun, Tolstoy remained close to Masha, who had earlier led an unhappy life, with marriage to an abusive husband and the stigma of an illegitimate child.

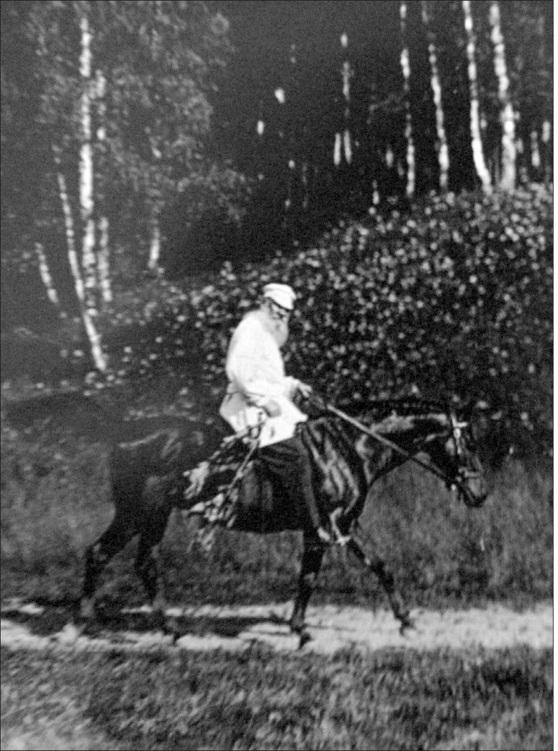

20. Tolstoy on horseback in the environs of Yasnaya Polyana, 1908. Tolstoy was a passionate horseman from early childhood. There was a point at the end of his life when he came to see even riding as a self-indulgent activity when there were peasants starving around him, and he pondered giving it up. He reasoned that his horse was old, however,

and so continued riding.

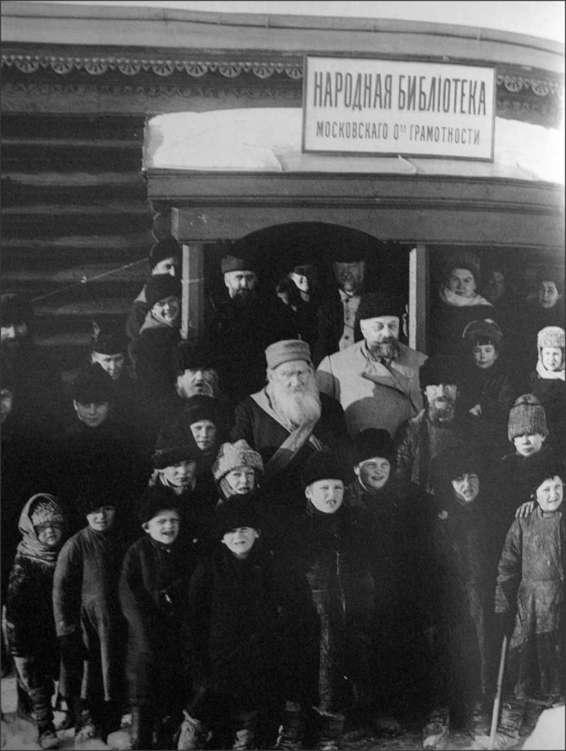

21. Tolstoy at the opening of the People's Library in Yasnaya Polyana village, 31 January 1910. As a young man, Tolstoy had been passionate about setting up schools, since there was no provision for the peasants to receive any education. The library, set up by the Moscow Literary Society, consisted of one small room with two bookcases. Pictured with Tolstoy are four pupils of his first Yasnaya Polyana school.

22. Repin,

Lev Tolstoy Barefoot,

1901. This famous portrait of Tolstoy 'at prayer' in the grounds of Yasnaya Polyana was first exhibited in St Petersburg just after Tolstoy was excommunicated, and drew hundreds of admirers who adorned it with flowers as if it was a popular icon. Seeking to avoid public disturbances, the authorities ordered it to be withdrawn when the exhibition travelled on to other cities.

10. PILGRIM, NIHILIST, MUZHIK

If I was on my own, I wouldn't be a monk, I would be a holy fool—that is, I wouldn't cherish anything in life, and would do no one any harm.

Letter to Nikolay Strakhov, 6 November 1877

1

AS SOMEONE WHO CAME TO BELIEVE

fervently in the idea that our lives are made up of seven-year cycles, and who was also extremely superstitious, Tolstoy was bound to look upon his forty-ninth year as being of special significance—particularly since this birthday fell in the seventh year of the seventh decade of the century. And so it was, for looking back in October 1884, when seven more years had passed, he realised that the most radical change in his life had indeed been, as he put it numerically in a letter to his wife, '7 x 7 = 49'.

2

It was in 1877 that Tolstoy began to tread more firmly on the path he had first tentatively started out on when he set up his Yasnaya Polyana school—the path of living in accordance with Christian ethics. Twice he had been diverted—when he married and again when he committed himself to writing

Anna Karenina.

But this time there was to be no straying, and the further he progressed along the path that was taking him away from his artistic calling as a novelist, and also away from his wife, the lighter his step became. He did not stop writing fiction entirely, but it became secondary to the more pressing task of exposing the hypocrisy and immorality he saw around him.

It was perhaps inevitable that a man who did nothing by half-measures would experience something beyond the typical mid-life crisis. The decade following Tolstoy's forty-ninth birthday would indeed turn out to be the most tumultuous in his life thus far. Moving to Moscow was the event which loomed largest for the rest of his family during this period (it was a life-changing experience for all the children and certainly for Sonya, after the long years of being sequestered at Yasnaya Polyana). But that was not what Tolstoy was referring to when he defined these years as a time of tempestuous inner struggle and change. He became a devout Orthodox communicant, then a trenchant critic of the Church. He undertook a root-and-branch study of all the major world religions and wrote a searing work of spiritual autobiography about his quest for the meaning of life. He produced a new translation of the Gospels, and set out to follow Christ's teaching. And then he began protesting loudly in the name of that teaching against the Orthodox Church. At the end of the 1880s Alexander III would brand Tolstoy as a godless nihilist, and a dangerous figure who needed to be stopped.

3

There was a journey to be undertaken before Tolstoy reached the point of formulating and articulating his new ideas, however, and it began with a period of intense religious searching, as reflected in the chapters at the end of

Anna Karenina

where Levin questions the meaning of life. The spiritual crisis that Dostoyevsky underwent during his years of Siberian exile in the early 1850s resulted in him jettisoning atheism and socialism and embracing Christianity, specifically Russian Orthodox Christianity, with ever greater fervour. Tolstoy did more or less the opposite, the spiritual crisis he underwent at the end of the 1870s resulting in him jettisoning not just Russian Orthodoxy but a large part of Christianity too. But he began his spiritual crisis by first becoming devout—the most devout he had ever been in his life.

Up until this point, Tolstoy had only notionally been a member of the Orthodox faith he was baptised into, like most members of his class. He had given up praying at sixteen and lost his belief at eighteen, but in his late forties he began to yearn for the guidance provided by strong religious beliefs. Writing to Alexandrine at the beginning of February 1877, Tolstoy confessed that for the past two years he had been like a drowning man, desperate to find something to hold on to. He told her he had been pinning his hopes on finding salvation in religion, that he and his friend Strakhov were both agreed that philosophy could not provide the answers, and that they could not live without religion. At the same time, he wrote, they just could not believe in God.

4

A month later, however, Tolstoy had changed course totally, and almost on a whim, after conversations with his 'materialist' doctor Grigory Zakharin and Sergey Levitsky, the celebrated 'patriarch' of Russian photography who had taken the group portrait of

The Contemporarys

writers in Paris back in 1856.

5

He started reading the theological writings of the Slavophile thinker Alexey Khomyakov, just like his character Levin at the end of

Anna Karenina.

6

Like Levin, he found them wanting. Even so, he was soon saying his prayers every day as he had in childhood, going to church on Sundays and fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays.

Tolstoy's newfound religious fervour did not stop him from going off hunting with his friends for wolves and elk, or seeking to publish his fiction profitably—yet. He had come back to his old publisher Theodor Ries to arrange for the separate publication of 'The Eighth and Last Part' of

Anna Karenina

after the

Russian Messenger

debacle, and soon after it appeared in print in July 1877 he handed over a slightly revised version of the complete novel for its first publication in book form the following year. The 1878 edition was never reprinted. By subsequently including the novel as part of his collected works, Tolstoy cunningly obliged all those who wanted their own copy to splash out on the complete set. In May 1878 he ascertained from his Moscow distributor that there were 2,700 copies left of the original print run of 4,800, and 800 unsold copies of his nine-volume collected works. The new, fourth edition of his collected works, planned for 1880, would be swelled by the addition of two final volumes incorporating

Anna Karenina,

and would go on sale for sixteen and a half roubles. If 5,000 copies were printed, Tolstoy wrote to Strakhov, that meant a total revenue of 82,500 roubles, of which 20,000 would go on printing costs, but he would sell the distribution rights for 30,000 roubles, so he stood to do extremely well out of the deal.

7

Tolstoy remained, as ever, a shrewd businessman when it came to financial negotiations. Nevertheless, there were also clear signs of his new piety. In the summer of 1877, accompanied by Strakhov, Tolstoy made the first of several visits to the famed Optina Pustyn Monastery in Kaluga province, some 135 miles west of Yasnaya Polyana. Tolstoy hoped to be granted an audience with Elder Ambrosy. He had heard about Ambrosy from his aunts, who had instilled in him and his siblings a reverence for Optina Pustyn from an early age.

8

His devout aunt Aline was even buried there, having made annual pilgrimages from Yasnaya Polyana. Tolstoy also knew about Ambrosy from his peasants. After a full day's travel, he and Strakhov arrived at three in the morning in their

tarantass.

Tolstoy did not want to be accorded special treatment because of who he was, and so they put up in the monastery's spartan and crowded hostel. It turned out that Father Feoktist, the monk running the monastery hostel, was one of his family's former serfs, however, and as soon as Count Tolstoy's identity was known, there was pressure on him to move to the more luxurious quarters available, which he resisted.