Tolstoy (48 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

There were reasons why Tolstoy chose to come to Optina Pustyn rather than any other monastery. Despite its sixteenth-century foundations, the anti-clerical reforms launched by Peter the Great and continued by Catherine the Great had almost forced it to close at the end of the eighteenth century, by which time there were only three monks left, and one of them was blind.

9

From this moribund state, however, Optina Pustyn recovered to become the centre of an extraordinary religious revival in the nineteenth century. This was due to its charismatic 'elders'. An elder

(starets)

was a monk who through long ascetic practice, constant prayer and solitude had become an unofficial leader of the spiritual life of his monastery.

10

Believing they possessed powers of healing and clairvoyance in addition to unusual wisdom, thousands of lay visitors would come annually from all over Russia to seek guidance from Elders on a wide array of problems in their lives. Many peti-tioners were peasants, but Optina Pustyn also attracted large numbers of the Russian intelligentsia, including many noted writers.

11

The ancient tradition of eldership was brought to Russia by disciples of the eighteenth-century spiritual leader Paisy Velichkovsky. At the age of seventeen, after taking his monastic vows, Paisy moved from his native Poltava to Mount Athos, where he established a hermitage and immersed himself in the Eastern Christian practice of Hesychasm ('inner stillness'). In 1764, after two and a half decades of attempting to reach a state of perpetual prayer and reconnect with the traditions of the early Church Fathers, he was invited to revive spiritual life in Moldavia. By the time of his death in 1794, the monastery he founded at Neamt had around 700 monks. As well as introducing eldership to the Slavonic world, Paisy Velichkovsky left an important legacy of published writings on prayer which were very influential on the monks who revived Optina Pustyn in the dark days of the early nineteenth century. The mystical texts he compiled for his Slavonic

Philokalia

('love of the beautiful'), in particular, cemented the vital link he had forged with the Hesychast traditions of Mount Athos and the early Christians who had lived in the desert. The nineteenth-century Russian elders who followed Velichkovsky's example were monks who emulated the Church Fathers by living in a remote hermitage, which was the nearest equivalent in Russia to retreating to the desert, and it is no coincidence that the word

pustyn

(hermitage) is related to the word

pustynya,

which means desert as well as wilderness. To ensure a stricter and more solitary existence than that of regular monks, however, the elders also lived in a

skete

—a kind of monastery within a monastery. At the time of Tolstoy's visit, the elder in charge of Optina Pustyn was Ambrosy, who was by then sixty-five, and one of the most famous men in Russia. It was Ambrosy upon whom Dostoyevsky would model his character of Zosima in

The Brothers Karamazov

following three meetings with him during his pilgrimage to Optina Pustyn in 1878.

Tolstoy was not best pleased that his cover was blown when he arrived at the monastery in May 1877, but it did mean that he was granted an audience with Ambrosy straight away. So many people came to see the elder that the vast majority would have to wait days or even weeks before being granted access (women were not allowed into the hermitage itself, but thronged round a specially built extension to Ambrosy's cell).

12

The spiritual assistance people requested was extremely varied. Mothers sought his advice on how to bring up their children, merchants wanted to know whether to make a particular purchase or not, uncles consulted him about whom their nieces should marry, while innumerable others sought prayers which might effect a cure for a grave illness, or merely some comfort in their afflictions.

13

Tolstoy came to Elder Ambrosy with no particular agenda, other than a hope that he might find answers to the spiritual questions which tormented him. After heeding Ambrosy's suggestion that he go to confession and take communion, Tolstoy stood through the four hours of the monastery's vespers service. He also spent time during his pilgrimage talking to the monastery's archimandrite (a Guards officer in his previous life), but his heart was most deeply touched by the ingenuous humility of Father Pimen, a former painter and decorator whose kind and down-to-earth ways had made him very popular with female supplicants. At one point in Tolstoy's conversation with the archimandrite, Pimen quietly nodded off on his chair,

14

but he was not as sleepy as he seemed. He later commented that Tolstoy had said a lot of eloquent but empty things, and should think about his soul. Ambrosy, meanwhile, later recounted to a friend of Strakhov, after a long sigh, that he had found Tolstoy challenging. In 1907 this friend published what the Elder had told him about Tolstoy:

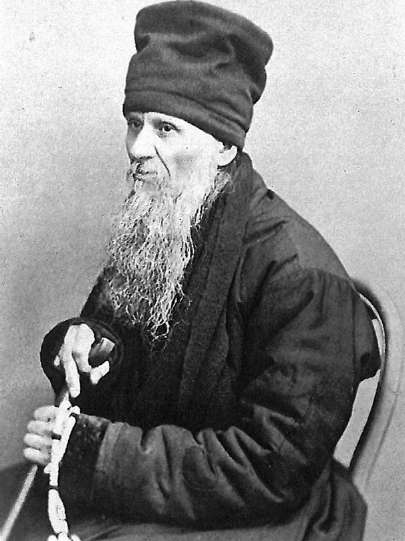

5. Father Ambrosy, the Elder at Optina Pustyn Monastery, whom Tolstoy visited for the first time in 1877

His heart seeks God, but there is muddle and a lack of belief in his thoughts. He suffers from a great deal of pride, spiritual pride. He will cause a lot of harm with his arbitrary and empty interpretation of the Gospels, which in his opinion no one has understood before him, but everything is God's will.

15

This same acquaintance told Strakhov privately at the time, however, that the Holy Fathers had thought Tolstoy had a 'wonderful soul', and were particularly pleased that he did not suffer from intellectual pride, unlike Gogol, who had visited the monastery in 1850. Wherever the truth lies, Tolstoy was buoyed by his first pilgrimage to Optina Pustyn—he was genuinely impressed by the wisdom of the monastery's elders, and by Father Ambrosy's spiritual powers in particular.

16

Meanwhile, his own faith was strengthened. When he returned to Yasnaya Polyana at the end of July, he started having long conversations with the local priest and getting up at dawn to go to early matins, saddling his horse himself so as not to wake his servant.

17

Russia had finally declared war on Turkey in April 1877, just as Tolstoy was finishing

Anna Karenina.

In the middle of August, accompanied by Sonya and various other members of their family, Tolstoy went to visit the Turkish prisoners of war who were being held at an old sugar factory on the road to Tula. He had hoped to start a new historical novel that summer, but news from the front kept preventing him from being able to concentrate, regardless of whether he was in a good or a bad mood, he wrote to Strakhov.

18

Tolstoy naturally could not help remembering being stationed himself on the Danube, before being transferred to the disastrous Sebastopol campaign during the Crimean War, and for a while he pondered writing Alexander II a letter about the state of Russia, and the reasons for the army's failures in the most recent hostilities with Turkey. But it was religion that was uppermost in his mind, and so it was faith that he wanted to talk about to the Turkish prisoners of war, not politics. He wanted to know whether they each had their own copy of the Koran, and who their mullah was.

19

Tolstoy's religious quest took him well beyond Russia's borders. The books which he asked Strakhov to send him later in the year included the Protestant theologian David Friedrich Strauss's

Old and New Faith,

a work which had caused almost as much scandal in Germany in 1872 as his 'historical'

Life of Jesus,

in which he had denied Christ's divinity some thirty years earlier. Tolstoy also asked Strakhov to procure for him Ernest Renan's

Life of Jesus,

an equally notorious volume with the same title which had provoked a storm of controversy in the Catholic world, and which had been banned in Russia ever since its first publication in France in 1863. Other authors who interested Tolstoy at this time were the orientalists Eugène Burnouf, who had published a history of Indian Buddhism in 1844, and his student Max Müller, later regarded as the father of

Religionswissenschaft.

Müller had become Oxford's first Professor of Comparative Theology in 1868, and wrote extensively on Indian philosophy and Vedic religion.

20

Strakhov continued to be a sounding-board for Tolstoy's ideas, but he was not thirsting for faith in the same way, and so did not accompany his friend on the next leg of his spiritual journey. As Elder Ambrosy had noted during their visit to Optina Pustyn, Strakhov's lack of belief was deeply entrenched; faith for him was 'merely poetry', despite an attraction to the monastic way of life which inspired him to travel to Mount Athos in 1881.

21

At Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy's newfound religious fervour was greeted with slight bemusement, particularly by Sonya, for whom Orthodox belief had always been an unobtrusive but integral part of her life. She was glad her husband had 'calmed down' after the violent mood swings of the previous years (particularly the periods of deep depression), and she could only rejoice that his character seemed to be changing for the better. In her diary, she was optimistic that Tolstoy had somehow reached the end of his spiritual journey:

Although he has always been modest and undemanding in all his habits, he is now becoming even more modest, meek and patient. And this eternal struggle that he began in his youth, aimed at achieving moral perfection, is being crowned with complete success.

22

She must have winced later at her naivety. Tolstoy's religious strivings certainly brought some peace and harmony to Yasnaya Polyana, but he had begun to walk alone, for none of his family felt inclined to take Christianity as seriously as he did.

Tolstoy's greatest inspiration at this time came from an unlikely source. Vasily Alexeyev, a thin, rather frail young man with a wispy ginger beard and candid blue eyes, was the latest tutor engaged to teach his eldest children, and he would have a surprisingly powerful influence on Tolstoy's evolving religious philosophy during the next few years.

23

In many ways, he was a Tolstoyan

avant le lettre.

He arrived at Yasnaya Polyana in October 1877 after being recommended by the Tolstoys' midwife Maria Abramovich (Sonya was at this point seven months pregnant with Andrey, her ninth child), and he was to stay with the Tolstoys for four years.

24

Given his background in radical politics, the surprising thing is not that Sonya eventually asked him to leave, but that he stayed as long as he did.

25

Alexeyev was openly socialist and atheist, and yet he was a model of Christian ethics in his personal conduct. He provided Tolstoy with much-needed moral support at this critical time in his life, and Tolstoy defended him to the hilt whenever his pious friend Sergey Urusov tried to attack Alexeyev as a 'nihilist' and 'the son of the devil'. 'I know few people other than him who are not only good, but kind and religious in feeling,' Tolstoy assured Urusov, another time stressing his meekness, and devotion to serving others.

26

Vasily Alexeyev was the son of a retired officer and minor landowner who had married one of his serfs, whom he was known to beat. He grew up in the far western province of Pskov, hundreds of miles from Moscow.

27

One of eight brothers and sisters, Alexeyev had excelled academically at an early age and won a place to study mathematics at St Petersburg University, where he became increasingly involved in left-wing politics. This was at the height of the Populist movement in the early 1870s and Alexeyev had got to know the revolutionary Nikolay Chaikovsky, leader of a circle involved in spreading socialist propaganda amongst the peasantry. It was Chaikovsky who introduced Alexeyev to Alexander Malikov, who was more of a religious idealist than a revolutionary and who came from a peasant background. Malikov had already spent time in prison and in exile because of his political beliefs, and now set his hopes on a mystical doctrine he had founded called Godmanhood, which combined socialist theory with Christian ethics. Seduced by his passionate oratory, Alexeyev became one of Malikov's followers, but the Russian government inevitably viewed attempts to disseminate the teaching of Godmanhood as revolutionary propaganda and promptly arrested him. Although Alexeyev was soon released due to the lack of incriminating evidence, his father disowned him.

Malikov and Alexeyev realised it was going to be impossible to put their ideas into practice in Russia, where they were seen as subversive. Along with about a dozen others, they decided to emigrate to America in 1875, hoping to fulfil their dreams of living a morally pure life in the Land of the Free. Chaikovsky was already there, having fled Russia to avoid arrest, and so was the positivist Vladimir Geins, another disillusioned revolutionary who had rechristened himself William Frey (the closest possible transliteration in Cyrillic of the English word 'free'). The group decided to settle in the Midwest. The southern part of Kansas had been acquired from the Native Americans only five years earlier, and land was extremely cheap. By pooling their resources, the group were able to buy 160 acres of land in Cedarville, near Wichita, for the total sum of twenty-five dollars. Crowding into the two rooms of the small farmhouse on their holding, the young Russian pioneers attempted to set up a utopian agricultural commune.

28

Although they augmented the two horses and a cow already on the land with more livestock, and sowed corn and wheat, there were immediate problems. No one knew how to milk a cow, for example. The community started out with noble ascetic ideals, and was happy to give up alcohol, meat, coffee, tea and sugar, but the fanatical and dogmatic Frey also banned bread, arguing that only food in its 'natural' state was acceptable. Medicines were also banned by him. But what finally undid the commune were the weekly meetings of 'mutual criticism' and 'public confession' which only exacerbated the numerous personal tensions that arose. The experiment was a disaster and the commune barely survived two years.