Tolstoy (54 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

Ivakin clearly found it sometimes a little challenging to work with Tolstoy, since the 'inimitable' author was even

partipris

when it came to translating the New Testament passages dealing with ethics which survived his ruthless editing. In

War and Peace,

Tolstoy had manipulated events and people to suit the particular view of history he was proposing. Now he wanted Christ's apostles to confirm views he had already formed:

Sometimes he would come running to me from his study with the Greek Gospel and ask me to translate some extract or other. I would do the translation, and usually it came out the same as the accepted Church translation. 'But couldn't you give this such and such a meaning?' he would ask, and he would say how much he hoped that would be possible.

106

Tolstoy spent a particularly long time mulling over the opening paragraph in the Gospel of St John ('In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God...'). He fairly swiftly decided to interpret the Greek

logos

as 'reasoning' rather than 'the word' (the Russian word

razumenie

implying both rational enquiry and understanding), but he then came up against the problem of translating

pros ton theon

('with God'), which the first Church Slavonic Bible renders as 'from God'. Dismissing the literal meaning of 'towards God' as meaningless, and condemning the Vulgate 'apud Deum' and Luther's 'bei Gott' as meaningless and also inaccurate, Tolstoy's far more radical version, on the basis of a lengthy discussion of the preposition

pros

was 'and reasoning replaced God'.

107

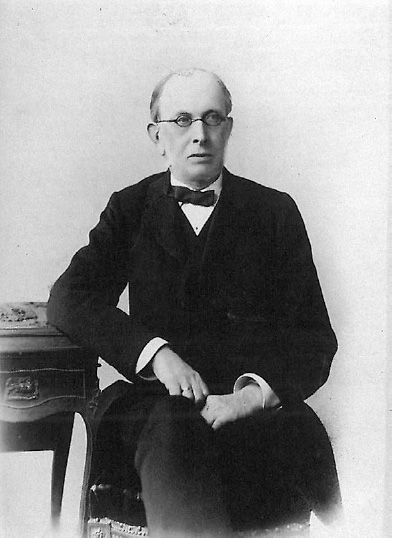

6. Konstantin Pobedonostsev, Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod from 1880 to 1905

By the time Alexander II was assassinated by revolutionaries on 1 March 1881, Tolstoy was ready to become, if not quite a Protestant, certainly a protestant in terms of the Orthodox Church, and his boldness was compared on more than one occasion with that of Luther, Jan Hus and Calvin.

108

Horrified by the thought of the conspirators being executed, Tolstoy sat down and wrote a letter to the new tsar, Alexander III, pleading for clemency in the name of Christian forgiveness. He then wrote a letter to the Chief Procurator of the Holy Synod, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, asking him to pass his letter on to the Tsar, and another to Strakhov, asking him to hand both letters over to Pobedonostsev. Sonya reacted with equanimity to having to go into national mourning by dressing in black crêpe from head to foot,

109

but she was aghast at her husband's latest action. It had been bad enough while he had been devout, and had insisted on observing the fasts on Wednesdays and Fridays. To retaliate, she had insisted on providing non-Lenten food for Vasily Alexeyev and Jules Montels, neither of whom were Orthodox, despite their readiness to eat what was offered, and she had then enforced the family's Lenten diet even more strictly when she noticed Tolstoy's faith wavering. On Good Friday, the strictest day of fasting, temptation had got the better of Tolstoy and he gave up eating Lenten food for ever after tucking into some of the meat that had been prepared for the two tutors. Sonya also stopped copying her husband's new manuscripts. She had found the pedagogical materials turgid, but the theological writing was far worse, and she confided in a letter to her sister Tanya that she had thought of leaving Tolstoy that spring. She reckoned that life at Yasnaya Polyana had been a lot better without Christianity.

110

She was also pregnant again.

The friction between the Tolstoys was now coming out into the open more and more frequently. When Sonya overheard Vasily Alexeyev supporting her husband's plea for clemency for the Tsar's assassins one morning over coffee, she exploded, terrified at the repercussions that Tolstoy's letter might cause. Alexeyev realised it was time for him to leave Yasnaya Polyana, and he asked Tolstoy for permission to make a personal copy of his Gospel translations to take away with him, knowing they could never be published in Russia. Since time was not on his side, he restricted himself to copying Tolstoy's Gospel excerpts and the general summaries in each chapter. This text was later prefaced by Tolstoy's introduction and entitled

Gospel in Brief.

It would be the first of his religious works to be published abroad. During World War I, Tolstoy's

Gospel in Brief

made a profound impression on Ludwig Wittgenstein, who chanced to find it in a bookshop in Galicia. He later claimed it had virtually kept him alive.

111

Friends and relatives who came to visit Yasnaya Polyana in the spring of 1881 were drawn into vituperative arguments about capital punishment and the Church, and Sonya started to worry that her husband's Christian charity was going to result in him giving away all they had to the poverty-stricken peasants who were coming to Yasnaya Polyana in ever increasing numbers, knowing they would not leave empty-handed. To begin with, Tolstoy wrote a thumbnail sketch of each petitioner down in his diary, noting, for example, one old woman's tears dropping on to the dust and another peasant's toothless smile (Tolstoy himself was toothless by this time).

112

Needless to say, Pobedonostsev refused to pass on Tolstoy's letter to the Tsar, and the conspirators were hanged in early April. 'Our Christ is not your Christ,' wrote Pobedonostsev crisply in the letter he finally sent Tolstoy in June.

113

Tolstoy brought his work on the Gospels to a halt that month, because he wanted to make another pilgrimage to Optina Pustyn. This time, instead of Strakhov, he took along as companion his servant Sergey Arbuzov, and instead of travelling by train he went on foot, dressed like a muzhik, complete with bast shoes he had specially commissioned from a peasant in the village.

They spent the first night sleeping on straw in an old woman's peasant hut, where they were woken at dawn the next morning by the swallows nesting in the roof. Four days later they arrived at the monastery, where they were put up without ceremony together with other peasant pilgrims in a dormitory infested with bedbugs. When word got out that the scruffy looking old peasant was actually Count Tolstoy in disguise, he was obliged to move to more salubrious accommodation, but it did mean that he was again granted an immediate audience with Elder Ambrosy, rather than having to wait almost a week. Tolstoy had not come to Optina Pustyn this time to find religious solace, but to challenge Ambrosy and the other monks about the Orthodox Church's distortion of Christ's teaching. He went away dissatisfied, having at one point demonstrated his superior knowledge of the Gospels.

114

On the way home, Tolstoy and his servant walked as far as Kaluga, which had quite a large population of sectarians, including Molokans and two offshoots of that sect, Subbotniks ('Sabbatarians') and Vozdykhantsy ('Sighers'), a tiny new faction whose believers, instead of crossing themselves, sighed while lifting their gaze upwards. Tolstoy set off to find them as soon as he learned this, to talk to them about their faith. He had been sickened to see the Optina Pustyn monks treat the destitute pilgrims with contempt while deferring to wealthy visitors, but he found the rest of the trip very invigorating.

In July 1881, a month after returning home, Tolstoy set off for his Samara estate with his son Sergey, who had just passed the end-of-school exams which were a requirement for university entrance. He felt listless there this time. He no longer had the stomach for working to make his land profitable, and the poverty in the region seemed to be even more starkly evident than in previous years. During this trip he had further contact with the Molokans, and attended one of their prayer meetings, after which two of their leaders came to visit him so they could continue the conversation. Naturally, Tolstoy was preaching to the converted when he read them extracts from his

Gospel in Brief,

for they also thought the Orthodox Church had mutilated Christ's teachings. On 19 July Tolstoy made an interesting new acquaintance when he met Alexander Prugavin, a young ethnographer who had become interested in the Russian sectarians after meeting many of them while exiled in the far north. Since 1879 Prugavin had been publishing articles in progressive journals about Russian schismatics and sectarians, ranging from the three Old Believer bishops Tolstoy had tried to help to the Pashkovites. Tolstoy was particularly interested to hear from Prugavin about a Tver peasant called Vasily Syutayev who had started preaching brotherly love and the abolition of private property. As soon as he learned from Prugavin that one of Syutayev's sons had refused to do military service, Tolstoy immediately declared that he wanted to meet him. The opportunity would soon present itself.

During his month out on the steppe, Tolstoy was affectionate in his letters to Sonya. He felt guilty. Many years earlier they had decided they would move to Moscow when the time came for Sergey to go to university, and that day had now dawned. With so much political unrest amongst the student body following the assassination of Alexander II, Sonya felt it was even more important to protect her son from being caught up in the revolutionary movement by going to live in Moscow herself. But this was also the liberation she had been longing for, particularly during the last few years when her husband had shunned any kind of social life, turning his back on his career as a successful novelist and condemning the depravity of their lifestyle. For Tolstoy, moving to Moscow was a nightmare prospect, and he had so far refused to help Sonya find somewhere for them to live. She was six months pregnant when she went flat-hunting in Moscow before he left for Samara, and she had to face the hot and dusty city the following month again in order to prepare everything for the family's arrival. Tolstoy suddenly felt remorse at having neglected her and left her to do everything on her own. He promised to help her on his return, yet when he returned home and found the house full of summer guests, he once again felt the painful contrast between his beliefs and his surroundings.

115

The nine Tolstoys left Yasnaya Polyana on 15 September, and took up residence in a rented apartment in a house in the best residential area of Moscow. Sergey became a student in natural sciences at Moscow University and Ilya and Lev became pupils at the very popular private boys' school founded in 1868 by Lev Polivanov, who had masterminded the Pushkin celebrations the year before. Later that autumn, Tanya became a student at the main art school in Moscow. Despite Tolstoy's pledge to help Sonya in Moscow, he soon forgot it. It was sheer misery for him to move to the city, and Sonya told her sister by letter that he was neither sleeping nor eating and had sunk into apathy, while she had spent the first two weeks constantly in tears. After he had arrived in Moscow, Tolstoy had gone to visit the city's slums, and had then returned home, walked up carpeted stairs to their new home and sat down to dinner, waited upon by two servants in white tie and tails.

116

The close proximity of luxury and poverty sickened him.

Relief came when Tolstoy escaped Moscow at the end of the month to go north to Tver province and meet Vasily Syutayev, the peasant sectarian Prugavin had told him about. Apart from their difference in social backgrounds, Syutayev was almost Tolstoy's mirror image in terms of their religious beliefs, which astonished him. Syutayev's doctrine of brotherly love was derived exclusively from the modern Russian translation of the New Testament, which he knew by heart, and like Tolstoy, he had dedicated his life to pursuing the ideal of self-perfection. Syutayev, who later came to visit Tolstoy in Moscow, was to become a source of deep inspiration for him.

117

Another source of spiritual support for Tolstoy at this time would come from his correspondence with his family's former tutor Vasily Alexeyev, and from his friendship with the librarian of the Rumyantsev Public Library, Nikolay Fyodorov, whose asceticism made Tolstoy's simple tastes seem positively sybaritic.

By the beginning of October Tolstoy was back in Moscow and trying to work. The walls in the flat proved to be paper-thin, however, so there was constant noise and he could not concentrate, for which he squarely blamed Sonya. He was also unhappy about her spending money needlessly. How could she have wasted twenty-two roubles on an armchair when that money could have bought a peasant a horse or a cow? Things improved a little after he rented two small rooms in another wing of the house for six roubles a month. Finally, he had some peace of mind, and to salve his conscience he crossed the Moscow river to go and chop wood every afternoon with the peasants on the Sparrow Hills. But relations with Sonya were no better. Two weeks before she gave birth, Sonya wrote again to Tanya to tell her that her husband had reduced her to complete despair. Tolstoy told his diary it had been the most painful month in all his life.

118

Alexey was born on 31 October. A few weeks later Tolstoy published a story about an angel in the new children's journal edited by Sonya's brother Petya. It was his first publication in four years.