Tolstoy (57 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

Although Tolstoy did not return to literature in the way Turgenev would have liked (fiction would never claim his attention again in the way it had earlier), he was nevertheless keen to honour his friend. He therefore readily agreed to speak at the commemorative meeting of Moscow's venerable Russian Literature Society that was planned for late October 1883, perhaps prompted by his conscience, having rather arrogantly refused to take part in the Pushkin celebrations in 1880. When it became known that Tolstoy was going to give a public lecture, the news spread rapidly throughout the city and was considered sufficiently important to be reported in the press. The head of press censorship wrote at once to inform the Minister of Internal Affairs: 'Tolstoy is a lunatic, you can expect anything from him; he may say incredible things and there will be a huge scandal'. Dmitry Tolstoy took action by informing the Moscow governor, Prince Dolgorukov, who promptly banned the commemorative meeting from taking place. There was bitter disappointment amongst the Moscow intelligentsia.

29

Count Dmitry Tolstoy was forced to deal with his anarchic relative about another matter that autumn. Tolstoy was appointed to be a juror for the Tula regional court, and his refusal to serve on religious grounds was again reported in Russia's main newspapers. Fearing that the authority of the courts might be undermined if others followed his example, this time Dmitry Tolstoy expressed his concerns to the Tsar.

30

But Tolstoy was now unstoppable. In 1883, instalments of

Confession

began to appear in the revolutionary émigré journal

The Common Cause,

which was based in Geneva.

31

The first separate edition of

Confession,

as it was now called, was produced by the journal's publisher Mikhail Elpidin the following year. Elpidin was another former seminary student turned revolutionary who had escaped from prison and fled abroad, where he also published the first edition of Chernyshevsky's

What Is to Be Done?

in 1867. The émigré edition of

Confession

was reprinted many times. In June 1883 a French translation of Tolstoy's

Gospel in Brief

was also published in a Paris journal. Its translator, Leonid Urusov, the vice-governor of Tula, and a friend sympathetic to Tolstoy's views, had already started working on a French translation of

What I Believe?

32

Tolstoy had planned to 'publish'

What I Believe

in

Russian Thought,

anticipating that hectographed copies of the proofs would circulate, following certain prohibition by the censor, as had been the case with

Confession.

It was now too voluminous to be submitted as an article, however, and Tolstoy resolved to publish it as a book instead.

33

The work on

What I Believe

had been intense, but in early October, exhausted but jubilant, he was ready to hand the manuscript over for typesetting. He made an interesting new acquaintance when he stopped off in Tula on his way to Moscow. The Sanskrit scholar Ivan Minaev, Professor of Comparative Philology at St Petersburg University, was Russia's greatest expert on Buddhism, and had travelled extensively in India. Tolstoy's interest in the Eastern religions was to grow exponentially in the last decades of his life, and he grilled Minaev for over five hours on the precise aspects of Buddhism on which he wanted clarification.

34

Although Tolstoy felt extremely lonely in the midst of his uncomprehending family, he was beginning to find more people from an educated background with whom he could have meaningful conversations, either in person or by letter. The first had been his children's teacher Vasily Alexeyev, who had moved out to work on his Samara estate in 1881, and with whom he was still in regular contact. People were also beginning to make their way to him. At the end of 1882 Tolstoy had embarked on an intense, brief correspondence with a former university student exiled on his father's estate in Smolensk province.

35

But it was in Vladimir Chertkov, who came to visit Tolstoy in Moscow in October 1883, that he found his greatest kindred spirit and most devoted disciple. From this point until Tolstoy's death Chertkov would occupy an ever more important role in his life as his closest friend and partner in their shared mission to disseminate what they saw as true Christianity.

Chertkov was twenty-nine when they met, Tolstoy fifty-five. He did not have a title, but his background was even more distinguished than Tolstoy's. Both his parents were descended from old aristocratic families (one paternal relative had founded the Chertkov Library which Tolstoy had worked in when he was writing

War and Peace),

and they were very close to the court. The future Alexander III was Chertkov's playmate when he was a child, while Alexander II was a regular visitor to the family's opulent mansion in St Petersburg while he grew up, and showed him particular favour from a young age. As well as inviting Chertkov and his parents to holiday at the Romanov palace in Livadia in the Crimea, the Tsar singled him out during cavalry parades. At the age of nineteen, after an elite education, Chertkov had followed his father into the army, where a brilliant career awaited him.

36

'Le beau Dima', as he was known, was enormously wealthy, as well as being tall, handsome, and on the guest list of all the most exclusive balls and social gatherings. He was also famous for a certain eccentricity: his refusal to dance with Empress Maria Fyodorovna on one occasion had caused a sensation in a world which took protocol very seriously. In 1879 Chertkov had taken an eleven-month leave, which he spent in England, and shocked his parents soon after his return by informing them of his decision to resign from the army. Since 1881 he had been living at Lizinovka, his parents' enormous estate in Voronezh province, where he had thrown himself into philanthropic works for the benefit of the peasants by setting up schools, libraries and training facilities.

37

Chertkov's desire to devote his life to the peasantry was not the only reason he was drawn to Tolstoy. He was also inspired by unorthodox Christian ideals which he initially inherited from his mother, who had become a Protestant evangelist after the untimely deaths of her eldest and youngest sons. It was his dynamic mother, Elizaveta Ivanovna, who had been instrumental in bringing Lord Radstock to Russia in 1874. It was she who had effected his introduction to all the best salons in St Petersburg, and introduced him to her brother-in-law, Colonel Vasily Pashkov, who carried on Radstock's work after he was expelled from Russia in 1878. One of the richest men in Russia, Pashkov also came from the aristocracy, but after becoming an evangelical Christian he had eschewed high society salons for prayer meetings held at his house, which sometimes attracted over 1,000 followers. He had also founded the Society for the Encouragement of Spiritual and Ethical Reading which disseminated copies of the Gospels translated into Russian, and other edifying literature. When Chertkov had gone to England, he naturally met with Lord Radstock,

38

who gave him introductions to the British aristocratic and political elite, including the future Edward VII.

39

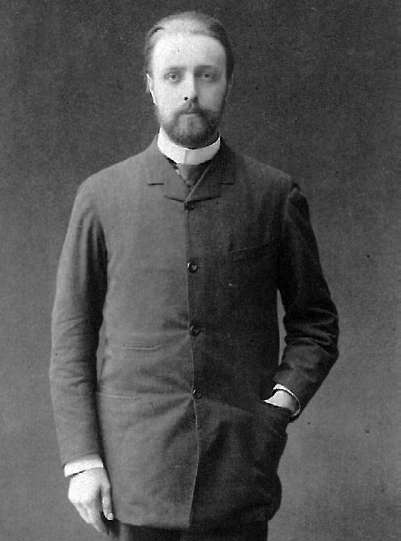

7. Vladimir Chertkov as a young man, 1880s

Chertkov had practised a Christian way of life since returning from England, but he was not an evangelist like his mother. His religious views were much more in tune with Tolstoy's beliefs, which explains why, when they met, it felt to them almost as if they were already old friends. Tolstoy was the first person Chertkov had ever known who shared his views on the incompatibility of Christianity with military service.

40

As for Tolstoy, he was dazzled by his young visitor, and the bond that was immediately formed between them was strengthened by not only their shared religious convictions, but also their common aristocratic background.

41

Chertkov had found his messiah and Tolstoy had found the confidant he had longed for. Throughout their friendship, much of their communication was by letter: their correspondence fills five separate volumes of Tolstoy's collected works in the edition which Chertkov launched in the 1920s. Tolstoy had also found in Chertkov an unexpected source of protection, for his friend's formidable connections to the court meant they could embark on their programme of planned activities with a degree of impunity.

42

As well as proposing a publishing venture, Chertkov wanted to help disseminate Tolstoy's writings abroad, and soon after their first meeting he began translating

What I Believe

into English, a language of which he had a flawless command.

43

Another new friend who provided crucial moral support in the later stages of finishing

What I Believe,

when Tolstoy felt like a 'writing machine', was Nikolay Ge, who came to Moscow to paint his portrait in 1884. In contrast to Kramskoy's portrait, in which the writer's gaze is firmly fixed on the viewer, Ge depicted Tolstoy sitting pen in hand at his desk, his head bowed over his manuscript in deep concentration.

44

By deliberately not showing Tolstoy's eyes, Ge broke with the conventional rules of portraiture, and many were shocked when his painting was first exhibited. Like Tolstoy, Ge was a firm believer in manual work (his speciality was building stoves), and he was one of the first 'Tolstoyans'. He tried to follow Tolstoy's precepts to the letter, and became a fanatical vegetarian, sometimes eating almost nothing at all. He also tried valiantly to make himself eat things he did not like, so refused buckwheat and chewed his way penitently through dishes of wheat grain with either hemp oil, or no oil at all, rather than butter. In 1886 he gave away all his property to his family. Like Tolstoy, he had a wife who did not share his views.

45

Tolstoy's strategy for getting

What I Believe

past the censor was to write from a deliberately subjective point of view, print only fifty copies and set the price at an eye-watering twenty-five roubles, but he was deluding himself if he thought his unequivocal rejection of both secular and ecclesiastical power would be condoned.

46

On 18 February 1884 the thirty-nine copies remaining at the printer were confiscated, but to Tolstoy's delight they were not destroyed. Instead they were sent to Petersburg, where, along with the eight copies which Tolstoy had been required to submit for inspection, they were delivered to the many high-ranking figures in the government and the imperial court who were anxious to read Tolstoy's latest work. They then passed the book on to others. In no time,

What I Believe

was also being lithographed and sold for four roubles a copy.

47

Tolstoy himself was a willing accomplice in the illegal samizdat operation, and paid scribes fifteen roubles to make copies of his manuscript for distribution.

48

French, German and English translations were soon underway.

What I Believe

was an important work for Tolstoy, and one he had been building up to in his previous religious writings. He took particular care with its exposition as it was the first systematic explanation of his religious and ethical views, his 'creed'. Tolstoy wanted a religion which would stand up to rational scrutiny. He wanted a clear, straightforward set of rules to follow in his daily life, and he found them in Christ's five commandments in his Sermon on the Mount, which can be briefly summarised as follows:

- Live in peace with all men ('anyone who is angry with his brother will be subject to judgement').

- Do not lust ('anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart') and do not divorce ('anyone who divorces his wife, except for marital unfaithfulness, causes her to become an adulteress, and anyone who marries the divorced woman commits adultery').

- Do not swear ('Do not swear at all: either by heaven, for it is God's throne; or by the earth, for it is his footstool; or by Jerusalem, for it is the city of the Great King').

- Do not resist evil ('If someone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also').

- Do not hate ('Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you').

If everyone followed these commandments, there would be no more wars and no need for armies. Indeed, living a Tolstoyan Christian life would eradicate the need for courts, police officers, personal property and any form of government. Morality was the cornerstone of Christianity for Tolstoy, and he now saw life in simple black-and-white terms. As he writes in

What I Believe: