Tolstoy (59 page)

Authors: Rosamund Bartlett

In April 1885 Chertkov opened a bookshop in Moscow, set up a warehouse in St Petersburg and hired a young female assistant, whom he would later marry, and a co-editor, Pavel Biryukov, who was to become another of Tolstoy's devoted friends and disciples (in time he would write a voluminous and reverential biography). Biryukov was a graduate of the Naval Academy, and had been working as a physicist in the main observatory in St Petersburg. He came from the nobility, but occupied a far lower place in the pecking order than either Chertkov or Tolstoy, which became a stumbling block when he tried to marry Tolstoy's daughter Masha a few years later.

73

The Intermediary was a huge success—12 million of the little books it produced were sold in the first four years of its existence. They filled a real gap in the market, where previously there was little available to the burgeoning numbers of literate peasants and urban workers beyond saints' lives and crudely written stories of a very low literary quality. Tolstoy advised Chertkov on which foreign authors to publish (including Dickens and Eliot), but he also made a very valuable original contribution himself. The Intermediary presented him with an opportunity to pick up the work of his

ABC

where he had left off, and, in fact, one of The Intermediary's publications was his story 'Captive in the Caucasus', which he had written back in the 1870s for his ABC.

74

He also wrote twenty finely executed new stories over the next few years for The Intermediary, and a select few journals.

75

These brief tales were considerably better crafted than the boots he made, which he proudly described to Sonya as 'un bijou'. Tolstoy was an expert at retelling fables and folk stories in a vivid and simple way, deploying humour and an admirably light touch with the moral each contained.

While Tolstoy was busy writing stories for the masses, his wife was learning the ropes in a different area of the publishing sector. Her very real anxieties about the family's loss of income had led Tolstoy to suggest that she produce the next editions of his collected works and his

ABC

books. Previously the sales of Tolstoy's collected works had been handled by the husband of his niece Varya (Masha's daughter). Sonya now decided to retain the rights to the publication of her husband's works, and to convert the outbuilding at their Moscow house into a warehouse. In January 1885 Sonya got down to business, and the proofs for the new, fifth edition started arriving the following month. New works by Tolstoy completed since 1881 which were earmarked for the new twelfth volume of this edition included his novella

The Death of Ivan Ilyich,

'Strider', and a couple of the stories Tolstoy had just written for The Intermediary, including 'The Tale of Ivan the Fool'.

76

In February Sonya set off to St Petersburg to obtain permission for this volume to be published, and also to consult Dostoyevsky's widow about the most profitable way to go about her new publishing venture. One of the most valuable pieces of advice from Anna Grigorievna was to give booksellers only five per cent discount.

77

She also recommended that Sonya should not insist on each volume being published in chronological order. Sonya proved to be an accomplished businesswoman. The twelfth volume was banned, but in November 1885 she was already making her second visit to St Petersburg to lobby for the ban to be lifted (it was eventually published in 1886), and to initiate the process of publishing the sixth edition of Tolstoy's works.

78

By 1889 she was already releasing the eighth edition.

79

Letting Sonya publish everything he had written before his spiritual crisis (plus the occasional new work of fiction) was Tolstoy's concession to her, and he helped her with the proofs, but he was much more interested in proselytis-ing. Since 1882 he had been working on and off on a major new treatise,

WhatThen Must We Do?,

which drew on his experiences in the Moscow slums while working for the census. Its topics were poverty, exploitation and the evils of money and private property, but the solution to these perennial problems was not technology or modernisation, but physical labour, humility and personal endeavour:

So these are the replies I found to my question: What must we do?

First: not to lie to myself; and—however far my path of life may be from the true path disclosed by my reason—not to fear the truth.

Secondly: to reject the belief in my own righteousness and in privileges and peculiarities distinguishing me from others, and to acknowledge myself as being to blame.

Thirdly: to fulfil the eternal, indubitable law of man, and with the labour of my whole being to struggle with nature for the maintenance of my own and other people's lives.

80

At the end of 1884 Tolstoy handed over the first chapters for publication in

Russian Thought.

Despite the eternal optimism of his editors, the censor vetoed their publication, but copies were naturally made from the proofs for informal distribution.

Tolstoy's religious works were now also beginning to reach a wide audience abroad: in 1884 Mikhail Elpidin had published

Confession

as a separate book for the first time in Geneva, and in 1885 French, German and English translations of

What I Believe

were published. In the volume

Christ's Christianity,

published in London, Chertkov included his translations of

Confession

and

The Gospel in Brief

along with

What I Believe.

Readers outside Russia thus became acquainted with Tolstoy's religious writings and his major fiction simultaneously, as if his entire career to date had been telescoped: while the first French translation of

War and Peace

appeared in 1879, it was not until 1885 that

Anna Karenina

was also published in French translation. The first English translations (completed by the American Nathan Haskell Dole) of both novels appeared in 1886.

81

While Tolstoy was keen to disseminate his ideas abroad, it was in Russia that he wanted to make an impact, and the first concrete sign that he was succeeding came in the spring of 1885, when it became known that a young man had refused to serve in the army on the grounds of his Tolstoy-inspired religious convictions.

82

A number of writers and thinkers now started to make an impact on Tolstoy's thought, as it continued to evolve. Although he had by now articulated the major tenets of his new worldview, he remained very receptive to currents of thought which seemed to echo or amplify his own ideas, and there were three important people who shaped his thinking in 1885: an American political economist in New York, a self-educated peasant in Siberia, and an émigré religious positivist based in London.

Henry George, who rose from humble origins in Philadelphia to stand against Theodore Roosevelt for Mayor of New York in 1886, was an evangelical Protestant who wrote a best-selling book in 1879 about social inequality called

Progress and Poverty

.

83

Articles about this book began appearing in the Russian press in 1883, and in February 1885 Tolstoy started reading the book itself. He was riveted by George's central idea that all land should become common property. Regarding it as a major turning point, he predicted that the emancipation from private ownership would be as momentous as the emancipation of the serfs.

84

George's philosophy was inspired by the observations he had made during his extensive international travels. He had noticed that poverty was greater in populated areas than in those which were less developed. In his book he argued for a single tax, so that private property, and ultimately poverty, could be eliminated. Tolstoy was all for the abolition of private property, but at this point he was quite hostile to the idea of a tax applied by a government, due to the element of coercion inherent in such an action. Nevertheless, he would come to change his mind a decade later, and wholeheartedly embrace George's proposals.

In July 1885 Tolstoy found himself being stimulated by another thinker in whom he recognised a kindred spirit when a political exile in Siberia sent him a manuscript by Timofey Bondarev. He had first read about

The Triumph of the Farmer or Industry and Parasitism

a few months earlier in a journal article, and was curious to read it. Taking his inspiration from Genesis 3: 19 ('By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food...'), Bondarev argued that it was each person's moral and religious duty to earn their bread through physical labour, regardless of their social station. Tolstoy was electrified by the ideas contained in this manuscript, and by the author's passionate diatribe against the wealthy ruling classes. He was also struck by the rich mixture of biblical and colloquial language the treatise was written in, and he read it aloud to everyone at Yasnaya Polyana on the day he received it. He then set about

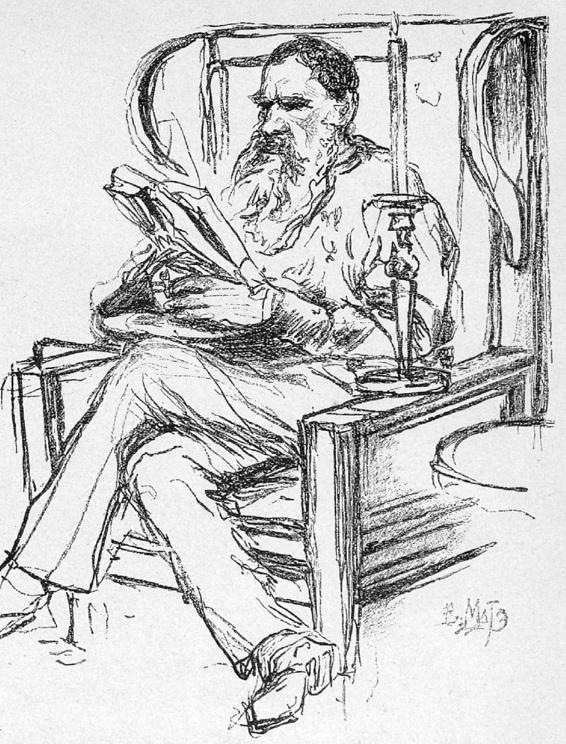

8. Pencil drawing by Repin of Tolstoy reading in his grandfather's chair at Yasnaya Polyana, 1887

writing to the author, and finding out more about him. Timofey Bondarev, it turned out, was a former serf from southern Russia. In the 1850s, at the age of thirty-seven, he had been forced to abandon his wife and four children when his owner recruited him into the army, where he faced the standard period of conscription of twenty-five years. In 1867, after serving for ten years, Bondarev was arrested for renouncing his Orthodox beliefs and becoming a Subbotnik ('Sabbatarian'—a splinter group of the Molokans). He was exiled for life to a remote village on the Yenisey river, not far from Mongolia, along with other sectarian 'apostates'. As he was the only person who could read and write in the village, he set up a school, in which he taught for thirty years. He devoted the rest of his time to tilling the land and writing his treatise.

Tolstoy agreed with 'everything' in the treatise, and entered into an enthusiastic correspondence with Bondarev, telling him that he frequently read out his manuscript to his acquaintances, though adding rather tactlessly that most of them usually got up and walked out. He also confided to Bondarev that this had given him the idea of narrating his manuscript whenever he had boring visitors: it was a successful ploy in getting rid of them.

85

Tolstoy went out of his way to get Bondarev's manuscript published. After its inclusion in the journal

Russian Wealth

was censored at the last moment in 1886, he persevered, only to see it being physically cut from

Russian Antiquity

in 1888. Eventually an edited version of Bondarev's manuscript, accompanied by an article by Tolstoy, appeared later in the year in

The Russian Cause,

its editor receiving a caution from the Ministry of Internal Affairs as a result.

86

Much later it was published by The Intermediary, prefaced by Tolstoy's introduction.

87

Both Bondarev and Syutayev were pivotal figures for Tolstoy in his quest to persuade people to live in harmony with the land, as he made clear in a footnote to

What Then Must We Do?,

which he finally finished revising in 1886:

In the course of my lifetime, there have been two Russian thinking people who have had a deep moral influence on me, enriched my thinking, and clarified my worldview. These people were not Russian poets, scholars or preachers, but are two remarkable men who are alive today, and have both spent their whole lives working on the land—the peasants Syutayev and Bondarev.

88

Another crucial person in Tolstoy's campaign to promote a life of non-violence in harmony with the land was William Frey, the gifted son of an army general from the Baltic nobility who had abruptly turned his back on a brilliant military career in St Petersburg in the 1860s in order to seek the truth. In 1868, at the age of twenty-nine, after dabbling with radical left-wing politics, Frey emigrated with his bride to America and changed his name from Vladimir Geins to the symbolic Frey ('free'). In the mid-i87os he had been part of the disastrous Kansas commune along with Vasily Alexeyev and Alexander Malikov, but in 1884 he moved with his family to London, by this time a fervent positivist, and a devotee of Comte and Spencer. The following summer he set off to preach the 'religion of mankind' in Russia, where he very quickly came across samizdat copies of

Confession

and

What I Believe,

which made a deep impression on him. After sending Tolstoy a sixty-page letter outlining the superiority of the 'religion of mankind', he received an invitation to visit Yasnaya Polyana, and he arrived in October 1885.

89

Tolstoy was enchanted by Frey, whom he described as a serious, clever and sincere person with a pure heart. He was not persuaded by Frey's arguments about religion, but he was encouraged by his example to persevere with his efforts to give up meat, alcohol and tobacco. And he was captivated by Frey's stories of life in the Wild West, and his experiences ofliving in communes where there was no private property, and where everyone worked with their hands rather than with their heads.