Tom Brokaw (33 page)

CHESTERFIELD SMITH

“No man is above the law.”

N

O MAN

is above the law.” That was the simple and direct opening of a statement issued by the new president of the American Bar Association on the Sunday after the infamous Saturday Night Massacre, when Richard Nixon fired the Watergate special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, prompting Attorney General Elliot Richardson and his number one assistant, William Ruckelshaus, to resign. Nixon's ambush of Cox was a startling and deeply troubling event. It did seem that this nation of laws was in a precarious state given the desperation and the power of the man in the White House.

I remember standing on the White House lawn that night, participating in a White House special report, when my colleague the late John Chancellor remarked, with chilling effect, “There seems to be a whiff of the Gestapo in the air of the nation's capital tonight.”

Chesterfield Smith, a gregarious and prosperous Florida barrister, had been president of the ABA for only a month when Nixon rattled the country and the legal establishment with his imperious action. Outwardly, Smith appeared to be the quintessential establishment lawyer. His entrepreneurial ways had turned his law firm into a powerful money machine in Florida. He was a Democrat, but he had voted for Nixon over McGovern. After serving as president of the Florida Bar Association and chairman of that state's constitutional revision commission, he had risen to the presidency of the ABA in record time.

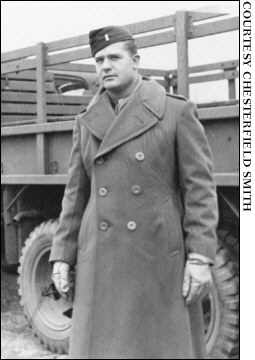

Chesterfield Smith, Camp Phillips, Kansas, October 1943

Smith, however, was a leader in reforming the legal establishment. He was quick to recognize the greatly expanded enrollment of women in law schools in the late sixties and early seventies. He began recruiting them for his firm, reasoning, “It would be better to get a smart woman than a dumb man, right?” Smith grew up in the segregationist South, and yet he was among the first to recruit minorities for a mainstream firm. He installed pro bono legal work as a fixed part of the firm's practice. In his unpaid role as chairman of the Florida constitutional revision commission, he took on what was called “the Pork Chop Gang,” canny legislators from sparsely populated north Florida who had controlled state politics for most of the twentieth century by beating back attempts to install one-man one-vote reforms. Smith won and helped make it possible for Florida to become a modern political state.

Smith believed so deeply that the law should always be viewed first as an instrument of public good and then as a means of making money that he refused to endorse his own firm's largest client when the man was running for governor. One of Smith's partner's says, “We lost the client, but I guess Chesterfield just thought the other candidate was better.”

Nonetheless, it was a long journey for Chesterfield Smith, from an itinerant boyhood in central Florida to his role as the conscience of the nation's leading legal organization on the weekend when the president of the United States, hunkered down in the White House, seemed to be sweeping aside the Constitution in his rage against his investigators. Curiously, Smith and Nixon had come of age in similar circumstances. They were two bright and ambitious men from families of modest meansâone in Florida, the sunny land of promise on the southeast coast, the other in California, the warm-weather anchor of the West Coast. Smith and Nixon were both World War II veterans with law degrees. Each in his own way rose through the common and trying experiences of his generation to become prominent in his chosen field.

Smith says his father “had an up-and-down life.” He was a schoolteacher for a while, then ran an electrical appliance shop near the town of Arcadia when power first became available to the remote cattle ranches in central Florida. When Florida went through a boom-and-bust period in the twenties, Chesterfield's father went out of business and on the road, looking for steady work. Eventually the family returned to Arcadia, where Smith finished high school at the top of his class without making much of an effort. He enrolled at the University of Florida as a prelaw student, but he'd stay only a semester at a time, dropping out to make money and raise a little hell. His childhood sweetheart, Vivian Parker, who was his wife for forty-three years before she died of cancer, was quoted as saying of Smith in those days, “He was just a poker-playing, crap-shooting boy who wouldn't settle down.” Smith agrees that this is a fair and honest description.

By the time Smith was twenty, America had passed the Selective Service Act, and rather than wait to be drafted, Smith enlisted in the Florida National Guard, which was mobilized for active duty in November 1940. Smith finished his basic training in Florida and was then shipped out to Officer Candidate School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where he trained as an artillery officer. He became part of the new 94th Infantry Division, and after marrying Vivian Parker at Camp McClain in Mississippi, he was sent to join General George Patton's 3rd Army in northern France about six weeks after D-Day. The poker-playing, crap-shooting boy from central Florida was in the thick of the war until the end, fighting across France and Belgium, participating in the Battle of the Bulge, then moving into Germany, the Ruhr Valley, and ultimately into Czechoslovakia.

By the time he was discharged, in the fall of 1945, he had been in the service sixty-one months, more than five years. He held the rank of major and had been awarded a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star. The circumstances of the wound that won him the Purple Heart are more dramatic than the injury. His outfit had paused along a major road en route to the Rhine River after the Battle of the Bulge. The men were out of their vehicles, resting, when suddenly never-before-seen airplanes appeared in the skies, the first jet fighters developed by the Germans.

Smith recalls, “They came roaring down the roads, strafing armored columns and people. I was one of the dummies. I remember being so amazed at seeing a jet plane I didn't run, and my left shoulder got clipped by a machine-gun bullet. It didn't hurt, but I did have to file a report, and that meant I got the Purple Heart. When VE Day came and they were sending people home on a point system, that little ol' nick was worth ten points.”

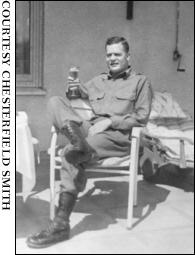

Chesterfield Smith,

wartime portrait

Chesterfield Smith,

ABA president, 1973

When he did get home, Smith also had a new outlook on life. His wife said later, “Something happened to Chesterfield's attitude in the war. I don't know just what, but he was a serious man when he returned.” He had not given up all of his old ways, however. He won $4,000 playing craps on the twelve-day voyage home. When he added that to his $3,500 in saved military pay, he had a comfortable start for his postwar life.

Smith was eager to start anew. “The way I was going before the war, I don't think I would ever have made it through law school,” he says. “But after the war I felt I had something invested in my countryâfive years of my life. I said to myself, Boy, you've got to settle down and make something of yourself, otherwise you ain't ever going to 'mount to nothing.”

Smith applied his military discipline to his law-school and family schedules. “I was very regimented about my duties,” he remembers. “I worked from seven

A

.

M

. till noon.” Then, not completely forgoing his past, he played golf every afternoon, returning home around four o'clock to be with Vivian and their firstborn through dinner. In return for his golf time, he did the baby's laundry; Vivian played bridge in the evening when Smith returned to his studies between nine o'clock and midnight. That was his schedule seven days a week. It paid off. Smith says, “I worked three hundred and sixty-five days a year and graduated in two years.”

“I was paid $115 a month under the GI Bill, and you could get by on that, but after about six months, when I got high grades, I became a student instructor and got another $90 a month. And we had almost $8,000 left over from the warâso we were doing fine. It was a methodical life, but we were men, not boys anymore.”

Smith graduated from law school with honors and was widely recognized as the class leader. He was a man in a hurry. “Hell,” he says, “here I was, almost thirty years oldâI wanted to get that law license and get into a practice and make myself some money.” He returned to Arcadia, his hometown, and joined a small firm. Two years later he joined Holland, Bevis, and McRae, a larger firm in nearby Bartow. His new employers could not have known that hiring the handsome young veteran from Arcadia would change the destiny of their modest firm.

One of the firm's leading clients worked with Smith shortly after he arrived in Bartow. He was impressed and went to the Holland, Bevis, and McRae partners with a message: “I've been your client for many years, but lately I've been dissatisfied. I like young Smith, however, and if you give him all of my work, well, I'll stay with you. If not, I'm taking my business elsewhere.”

Smith was made a partner in record time. He was a primary force in getting the firm into the lucrative and growing business of representing central Florida's phosphate industry; this proved to be a legal gold mine. At the same time, Smith was attracting a wide band of admirers. He was elected president of the Florida Bar Association, and that in turn led to his chairmanship of the state constitutional revision commission.

Simultaneously, Smith was becoming more involved with his profession through the American Bar Association. He met and became close to Lewis Powell of Virginia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg of New York, future justices on the U.S. Supreme Court. He says, “Powell appointed me to a committee called Availability of Legal Services. We made sure people who needed legal representation and didn't know where to turn or couldn't afford a lawyer, that those people could get a lawyer.” It was a radical idea at the time, but it changed the face of American law, leading to more pro bono work within established firms, legal ombudsmen, and the Legal Services Corporation.

Those were active years for Smith in his firm and in public service. He received no compensation for the sixteen months he directed the rewriting of Florida's antiquated constitution. Besides establishing one-man one-vote, Smith installed provisions for periodic citizens' review of the constitution and language that would make it impossible for a willful minority to amend the state's fundamental laws for narrow, self-serving purposes. His law firm was thriving during Florida's big-growth years, but Smith saw even more opportunity in a merger with a substantial Tampa firm, Knight, Jones, Whitaker, and Germany. The new firm became Holland and Knight, a veritable colossus of the law, one of the largest and most prosperous legal establishments in the country. It now has 734 lawyers in eighteen offices around the United States and in Mexico City.

In addition to its lucrative practice, Holland and Knight, under Smith's sure hand, became a model of diversity. He is characteristically modest about his contributions. “It was the firm willing to do it,” he says. “I think the people at the firm learned that African Americans, that women, that Cubans, Israelis, Japanese, Koreans, could all make a contributionânot because of their race or gender but because they were smart and worked hard. Once we learned that, we didn't have trouble with discrimination anymore. For example, I get a little more credit than I deserve for helping women. I was really kind to

talented

women. If they could help me, I could help them.”