Tom Brokaw (37 page)

He's also commander of a national campaign to build a World War II memorial in Washington, D.C. The $100 million fund-raising drive became the primary focus of his life following his loss to Bill Clinton in the 1996 presidential election. President Clinton unveiled the design for the memorial on the same day he awarded Dole the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian award. Typically, Dole had a quip for the occasion, saying he had originally hoped to be there that day to accept the key to the front door of the White House.

Then, as he has in recent years, he became emotional as he talked about the meaning of World War II. Dole believes the memorial, which is to be located on the Mall at the Washington Monument end of the reflecting pool, is necessary to remind the world that just men and women can prevail. He wants it to be a backdrop for World War II's unrealized ideals, a platform for America's children to speak out for freedom, decency, and human democracy.

In his White House remarks that day, Dole was particularly eloquent. He said, “I've seen American soldiers bring hope and leave graves in every corner of the world. I've seen this nation overcome Depression and segregation and communism, turning back mortal threats to human freedom.”

He was describing his own life and the monumental legacy of his generation in a few well-crafted words. It was just a moment in the life of this complicated man from the Kansas prairie, his right arm dangling at his side, those dark and flashing eyes filled with emotion, but it was a moment to savor, for it represented the many sides of Bob Dole. Public servant, wounded veteran, proud patriot, elder statesman.

Dole, now in his sunset years, misses the action of the Senate, the urgency of public discourse and political maneuvering on the critical issues of the day, but he's found a new calling in his determination to get the World War II memorial finished. He lives by the lessons he learned when he was bitter and recovering from his combat wounds. “For a while,” he says, “I subtracted five years from my life, but I caught up. People move on. That's the way it is in America. Don't just dwell on the past. Gotta look ahead.”

DANIEL INOUYE

“The one time the nation got together was World War II. We

stood as one. We spoke as one. We clenched our fists as one.”

W

HEN BOB DOLE

of Russell, Kansas, got to know Danny Inouye of Honolulu in that rehabilitation hospital in Michigan after the war, they had a good deal in common for two young men from such distinctly different backgrounds. Both were trying to learn to live without the use of an arm as a result of combat wounds suffered as Army lieutenants in the mountains of Italy. As a result of their injuries, both were forced to give up dreams of becoming physicians after the war. They also shared a direct style of dealing with people and an ironic sense of humor.

However, Inouye's route to that hospital took a few turns not imposed on the young man from Kansas. Inouye was a Japanese American, raised in Hawaii and named after the Methodist minister who had raised his orphaned mother. On December 7, 1941, Inouye, who was just seventeen, was preparing to attend church when he heard a hysterical local radio announcer exclaim that Pearl Harbor had been attacked.

He rushed outside the family home in Honolulu. In the distance he could see great volumes of smoke. “Then,” he remembers, “three planes flew over. They were gray with large red dots. The world came to an end for me. I was old enough to know nothing would be the same.” The land of his ancestors, the nation his grandfather had revered, had attacked the United States and, by extension, Danny Inouye, U.S. citizen.

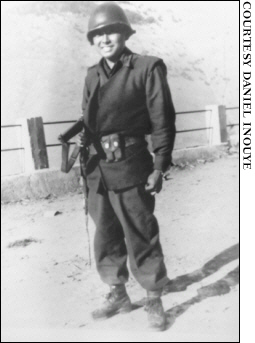

Daniel Inouye, wartime portrait

Young Inouye was enrolled in a Red Cross first-aid training program at the time, so he went directly to the harbor and began helping with the hundreds of casualties. In effect, he was in the war from the opening moments. He stayed on duty at the Red Cross medical aid facility for the next seven days.

In March 1942, the U.S. military repaid Inouye by declaring that all young men of Japanese ancestry would be designated 4-C, which meant “enemy alien,” unfit for service. Inouye says, “That really hit me. I considered myself patriotic, and to be told you could not put on a uniform, that was an insult. Thousands of us signed petitions, asking to be able to enlist.”

The Army decided to form an allâJapanese American unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Its shoulder patch was a coffin with a torch of liberty inside. The motto was “Go for Broke.” Before the war was over, the 442nd and its units would become the most heavily decorated single combat unit of its size in U.S. Army history: 8 Presidential Distinguished Unit Citations and 18,143 individual decorations including one Medal of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 560 Silver Stars and 28 Oak Leaf Clusters in lieu of a second Silver Star, 4,000 Bronze Stars and 1,200 Oak Leaf Clusters representing a second Bronze Star, and at least 9,486 Purple Hearts.

The regiment trained at Camp Shelby in Mississippi, and Inouye remembers that he and the other Nissei (second-generation Japanese American) soldiers didn't know what to expect. “We'd only heard about the lynchings,” he says, “but to our surprise these people were very good to us. We were invited to weekend parties and picnics, and for the first time in my life I danced with a white girl.”

Back at the base, Inouye says, other troops were not as welcoming, but “the problems were minimal because they could see we had a whole regiment!” Besides, the treatment by Mississippi civilians, the famed Southern hospitality, gave the young men of the 442nd new confidence after their original classification as “enemy aliens.”

Inouye's experience in Mississippi was a reflection of the racial schizophrenia loose in America. The Magnolia State was the epicenter of discrimination against black citizens, treating them as little more than paid slaves, and yet it made the extra effort for Japanese American soldiers at the same time the U.S. government was shipping their families off to internment camps.

Inouye and his buddies went from Mississippi directly into combat with the 5th Army in Italy. They were out to prove something. “I felt that there was a need for us to demonstrate that we were just as good as anybody else,” he says. “The price was bloody and expensive, but I felt we succeeded.”

After three months of heavy fighting in Italy, during which Inouye was promoted to sergeant for his outstanding traits as a patrol leader, the 442nd was called upon to perform one of the legendary feats of the war: rescue 140 members of a Texas outfit that had been caught in a German trap in the French Vosges Mountains. Another Texas division had tried and failed to get their fellow Lone Star Staters out, so the 442nd was sent in.

Inouye remembers, “We only had two thirds of our regiment after the Italian campaign. We had to fight hard for four straight days. We knew this was

the

test. We knew we were expendable. We knew it would have been unheard of to call on another regiment to rescue us. They were asking these brown soldiers to rescue these tall Texans. Our casualties exceeded eight hundred, but we rescued them.”

Inouye's role was so impressive that he was awarded the Bronze Star and won a battlefield commission as a second lieutenant. The 442nd also won the admiration of commanders throughout the Army. “After that,” Inouye says, “we were in demand.”

They were sent back to Italy to continue the long, bloody battle for control of southern Europe. In the Po Valley, Lieutenant Inouye was leading an assault against heavily fortified German positions in the mountains when he was hit by a bullet that went through his abdomen and exited his back, barely missing his spine. He continued to charge, gravely wounded, making a one-man assault on a machine-gun nest that had his men pinned down. He threw two grenades before the Germans hit him with a rifle-launched grenade. His right arm was shattered. He pried a third grenade from his right hand and threw it with his left. He continued to fire with his automatic weapon, covering the withdrawal of his men. Finally, he was knocked out of action by another bullet in the leg, but by then the German position was neutralized. Twenty-five Germans were dead, and Inouye took eight as prisoners of war.

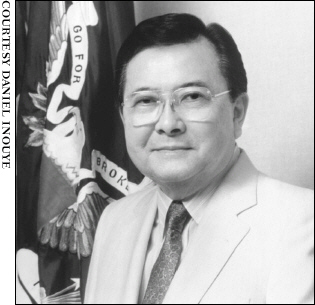

Daniel Inouye, senatorial portrait

Inouye was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his gallantry, and many believe that if he had not been a Japanese American he would have won the Medal of Honor. He was shipped back to the United States to begin treatment for his extensive injuries, and it was in the hospital that he met Bob Dole.

As the two became friends, Dole often talked about getting a law degree and going into politics back home in Kansas, maybe running for Congress. Inouye thought that wasn't a bad plan for the future and began to think about law school and politics as a possible career for himself.

He spent twenty months in hospitals before his discharge as a captain. On a layover in Oakland, California, on his way back to Hawaii, he decided he wanted to get, as he puts it, “all gussied up so when I got home Mama and Papa would see me in all my glory. I went into an Oakland barbershopâfour empty chairsâand a barber comes up to me and wants to know if I'm Japanese. Keep in mind I'm in uniform with my medals and ribbons and a hook for an arm. I said, âWell, my father was born in Japan.' The barber replied, âWe don't cut Jap hair.' I was tempted to slash him with my hook, but then I thought about all the work the 442nd had done and I just said, âI feel sorry for you,' and walked out. I went home without a haircut.”

Remembering the plans of his friend from Kansas, Inouye utilized the GI Bill to get a law degree from George Washington University. He returned to Hawaii and became active in local politics, serving as a prosecutor and in the territorial legislature before Hawaii became a state.

When Hawaii was admitted to the Union, Danny Inouye was a natural choice to become the state's first congressman, and he was elected overwhelmingly. It was an arresting moment in the well of the House of Representatives when Sam Rayburn, the larger-than-life Speaker, intoned, “Raise your right hand and repeat after me . . .” Of course, the new congressman from Hawaii had no right hand. Danny Inouye raised his left and took the oath of office, the first U.S. representative from his state and the first Japanese American in Congress. As another congressman said later, “At that moment, a ton of prejudice slipped quietly to the floor of the House of Representatives.”

After just one term in the House, Inouye was elected to the Senate in 1962, and he's been successfully reelected six times. He's highly regarded on both sides of the aisle for his middle-of-the-road Democratic party principles and his measured, almost stately style. When a

Washington Post

reporter asked him how he reconciled his laid-back demeanor as a senator with his record as a fearless, hard-charging member of the 442nd, he answered with a shrug and a laugh: “I was young. I was eighteen, first time leaving Mama. I had no strings, no sweetheart.”

Inouye's reputation for fairness has served him well on the Senate Watergate Committee investigating the Nixon White House and as chairman of the Senate committee that investigated the Iran-

contra

scandal during the Ronald Reagan administration. Former senator Lowell Weicker of Connecticut, a Republican and not an easy judge of other public figures, has said simply, “There is no finer man in the Senate.”

Inouye also knows how to make a point. He was a lead sponsor of the bill to get reparations for the Japanese American families interned during the war, and there were very few senators who could look at this quiet man with the Japanese surname, valorous military record, and empty right sleeve and vote no.

On another occasion, the Senate was considering a bill to place a limit of $25,000 on rewards “for pain and suffering” in product liability suits. It was a hot issue in the Senate Commerce Committee, where Republicans were determined to rein in corporate exposure in lawsuits. Then Senator Inouye spoke up, saying, “It's easy for those who have not been the victims to set the caps.” End of argument. End of bill.

Daniel Inouye, “Danny” to all his fellow senators and his friends, has just finished his sixth term as a U.S. senator. In September 1998, he turned seventy-four. He was a teenager when he saw those Japanese planes, “with pilots that looked like me,” and knew that his world was changed forever. What he did not know at the time was how much he would shape the new world through his bravery and his commitment to public service and the end of discrimination.

What he does know now, as he looks back, is that this country has been divided at critical times in its past, during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War; but, as he says, “The one time the nation got together was World War II. We stood as one. We spoke as one. We clenched our fists as one, and that was a rare moment for all of us.”