Tommy's Honor (19 page)

Authors: Kevin Cook

Where would Tommy Morris defend his title? One day the likely site was Prestwick, another day St. Andrews or North Berwick. After their spring meeting the Prestwick members scattered to their homes and estates. They could vote on Open matters only at their spring and autumn meetings or by returning for what was called an Extraordinary General Meeting. The fate of the Open was not deemed critical enough to warrant such a meeting. Spring and summer passed; the hourglass ran out. The Open Championship of 1871 was canceled.

Every ten years the Scottish government undertook a census. In the census of 1871, Thomas Morris Jr. of St. Andrews, asked to provide his occupation, answered that he was a golf-ball maker. Later a clerk in the local census office crossed out those words and wrote “Champion Golfer of Scotland.” Open or no Open, everyone knew who Tommy was.

“This youthful hero having thus effectually swept the board, matters came rather to a deadlock,” wrote Everard, “and for a year there was an interregnum.” While the officers of the Prestwick Club, the R&A, and the Honourable Company debated the Open’s future, the champion entered one of the busiest stretches of his career. Downing all comers in money matches, he found himself earning more in a good month than his father earned in a year, and when strokes and odds were no longer enough to lure challengers, he dreamed up stunts. In one match he played his own ball against the best ball of Davie Strath and Jamie Anderson, two of the best professionals in Scotland. And beat them. Later he spent a solid week playing high-stakes golf alone: He did it by backing himself—betting that he could play the St. Andrews links in 83 or better. That gaudy number enticed many R&A members. Their own Sir Robert Hay had recently won the club’s Royal Medal with a 94. All week the stakeholder’s pockets were packed with coins and banknotes the members had bet against Tommy, and each day Tommy took the money home. Playing in sunshine, wind, and rain, he won for six days in a row. After a rest day on Sunday he felt a surge of Christian charity, or so he said, and offered the bettors a chance to recoup. They were reluctant to try him again. He convinced them by dropping the number to 81, a mere four shots above his course record. That spurred a flurry of wagering. Of course he shot 80, capping what some called the first perfect week since Genesis.

The golfer and course designer C.B. Macdonald, four years younger than Tommy, would laud his hero’s “dashing style” and “unconquerable spirit.” J. Gordon McPherson, in his

Golf and Golfers,

wrote that only Tommy could lift his game by trying harder, a feat that was then called pressing: “Young Tom Morris was the only one we ever knew who could succeed in almost every case of pressing.” Golf fanatics swore he could “lay in the weeds” for ten or twelve or seventeen holes, then summon some last-minute magic to send his followers into glad hysterics. “[A]s for a bad lie,” another contemporary wrote, “he seemed positively to revel in it.” His father never forgot a niblick shot Tommy hit in a match at Musselburgh. He had an awkward lie, his ball below a tuft of grass in a deep divot. Another player would have been glad to advance the ball fifty yards, half the carry of a full niblick. Not Tommy Morris. As he took his stance, practically kneeling, he shot his father a look as if to say, “Watch this.” He hooded the face of his niblick and swung full out. The ball cleared the divot’s lip by an eyelash and rode a low line almost 200 yards to the green.

He must have felt invincible. Otherwise he would not have agreed to play against a man armed with a bow and arrow.

The R&A golfer James Wolfe Murray was also a member of the elite Royal Company of Archers, the queen’s ceremonial bodyguards in Scotland. He and Tommy squared off in a ballyhooed match in which the young champion hit golf balls while Wolfe Murray played true target golf, shooting arrows around the links. Dogs and boys scampered ahead of the players, the boys taking care to stay out of the bowman’s range. Golfers could only dream of hitting balls that tunneled through the wind like Wolfe Murray’s arrows, which soared on long, three-hundred-yard arcs. From closer range he could make an arrow come almost straight down, a literal bolt from the blue. He had nothing to fear from bunkers, though he looked comical standing chest-deep in a pot bunker, pulling back his bowstring and letting fly. Tommy’s sole advantage was on the greens, where his opponent found it hard to shoot an arrow into the hole from more than two or three yards. His efforts left arrowhead-divots around the hole on every green, and when he sank a “putt” it often caved in the hole on one side.

Tom Morris, walking along with the spectators, puffed his pipe and shook his head. Was this what the old game had come to—a circus act? In the half-century of Tom’s life, golf had grown from local pastime to national sport. In the past five years it had grown so swiftly that otherwise sane men were willing to bet on a match between a golfer and an archer. God only knew where the game was going next, but Tom knew one thing: It would be his job to repair the caved-in holes.

Tommy won most of the short holes, but as the match wore on and they turned to play against the wind, the bow’s power proved too much for him. Wolfe Murray pulled ahead on the inward nine, and for once Tommy was outshot.

Photo 9

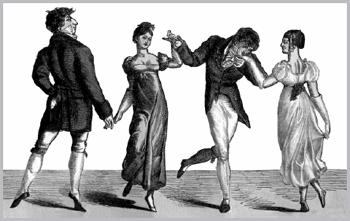

Quadrille dancing, the latest fad from France, stirred romance at the Rose Club Ball.

IGHT

The Better Ball

J

ohn Blackwood stood on the teeing-ground at eight

A.M.

, the hangman’s hour, dressed in his red jacket and white leather breeches. The new captain of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club was up early for his ceremonial Driving-In on the last day of the club’s Autumn Meeting. Surrounded on this cold October morning by a red-coated brigade of fellow members, he waited while Tom Morris teed him up. Tom, still red-cheeked from his morning dip in the sea, dropped to one knee, made a thumb-sized sand tee and placed a ball on top. Blackwood waggled. A few yards away another R&A officer stood beside a little Prussian cannon, watching Blackwood’s every move, for timing is everything in cannonry as in golf.

Blackwood swung—a booming drive, thanks to the cannon’s boom at the moment of impact. He was now “winner” of the R&A’s oldest prize, the Silver Club, which had been competed for in the R&A’s first century but now went automatically to the newly elected captain, who claimed it with this one symbolic swing. In later years the Driving-In ceremony would inspire another tradition: The caddie who retrieved the captain’s ball got a gold sovereign that was worth a fortnight’s pay. When the duffer Prince Albert, the future King George VI, drove-in one year, the caddies were accused of standing “disloyally close to the tee.”

Later, on Medal Day, the new captain led R&A golfers to the links, where Tom Morris waited. Tom doffed his cap to each one, then gave a little speech. They were about to play for the Royal Medal, he said, donated by His Late Majesty King William IV. The club’s Gold Medal would go to the man with the second-best score. The format was stroke play; he who finishes eighteen holes in the fewest strokes wins. They would play by St. Andrews rules, of course.

Tom started each twosome on its way, saying, “You may go now, gentlemen.” Later he stood by the Home green to greet the players as they came in. After the last group holed out he pulled the flag from the Home green and waved it over his head, signaling the cannoneer. Another cannon blast signaled the end of Medal Day.

At a lavish dinner that evening, the captain presented the medals to the winners. The highlight of the week, however, was the following night’s Royal and Ancient Ball, sometimes called the Golf Ball. Starting at ten

P.M.

, carriages delivered many of Fife’s leading citizens to St. Andrews’ Town Hall, a turreted Scottish-Baronial castle that glowed from within, its keyhole windows lit up like jack-o’-lantern eyes. Few commoners passed through the doors; no one would have dreamed of inviting the greenkeeper. Worthies from Edinburgh and London handed their canes and black hats to attendants while their wives and daughters rustled past in long dresses of silk and satin. Under the dresses, corsets ribbed with whalebone pinched the women’s waists as near as possible to the ideal of twenty inches around. These pinched women smiled behind fans made of ostrich feathers.

Moving from the doors to the Town Hall’s cavernous ballroom, revelers passed relics of St. Andrews’ long history: a wooden panel showing the town’s coat of arms and the date 1115; a rusted set of handcuffs; a headsman’s axe that cost the town treasurer six shillings “for shairpine the aix” before a 1622 beheading. In the ballroom, guests danced in groups of four couples, the couples changing partners as they moved in measured paces from the corners to the center of a six-pace square. Quadrille dancing was the latest fad from France. A forerunner of square dancing performed to the music of a small string ensemble plus a trumpet or French horn, the quadrille mixed and matched couples as they traded partners, stirring the social stew.

The ball lasted long into the wee hours. The

St. Andrews Citizen

always carried a long account of the event, listing dozens of dignitaries who attended. For weeks no one in town spoke of anything else, or so it seemed to Tommy. The twenty-year-old Champion Golfer could not help noticing that the Royal and Ancient, which had dickered over £10 or £15 when the issue was sponsoring the Open, threw banknotes at a caterer and a confectioner and brought a quadrille band from Edinburgh when the R&A Ball came around.

November frosts hardened the links. In December the sun set at four in the afternoon. Tommy played an occasional match to keep his muscles loose, but as the year without an Open wound down, there were no matches or tournaments to kindle his interest.

Perhaps there was another way to remind the gentlemen that he was still alive.

“On Friday night the Town Hall was the scene of a gay and brilliant assemblage on the occasion of the first ball given by the St. Andrews Rose Golf Club,” the

Citizen

reported on January 6, 1872, three months after the latest R&A Ball. “Over the civic chair in the center of the platform hung a large sized group [photograph] of the members of the club, on the right of which was the medal of the club, and on the left the beautiful champion golfer’s belt, won by Young Tom Morris three years in succession, which entitled him to retain it…. At the front of the hall was a large cross, with a garland of evergreens and the words ‘Rose Golf Club.’ The orchestra, which was occupied by an efficient quadrille band, was hung with scarlet cloth and ornamented with garlands of evergreens…the whole being overhung with a beautiful new flag of the Club. Refreshments were served in the Council Chamber, and purveyed by Mr. G. Leslie of the Golf Inn, and Mrs. Thomson, confectioner. The ball was opened at about half-past nine by the Captain of the Club, Mr. James Conacher, and dancing was kept up with the greatest spirit until about half-past four in the morning.”

Tommy and the enterprising Conacher had chipped in to rent and decorate the same ballroom where the almighty Royal and Ancient cavorted every fall. Now it was dark winter but the place was even brighter than on the night the wheezing ancients gathered here to try to dance. The Rose Club Ball was a livelier affair for a younger crowd, its quadrille dancers moving on nimbler limbs, changing partners in kaleidoscopic patterns while the buckle of the Championship Belt reflected light from half a dozen chandeliers.

Someone tapped Tommy’s shoulder and put a glass of champagne in his hand. He took a gulp, thinking perhaps of Dom Perignon, the French monk who added yeast to wine in 1668 and exclaimed,

“Je bois des etoiles”

—“I am drinking the stars.” Holding his glass in a white-gloved hand, Tommy felt stars percolate down his gullet. A moderate drinker, he was willing to temper his moderation tonight. Looking around the ballroom he saw his brother Jimmy trying hard to look older than his years, telling anyone who would listen that he’d be sixteen next week; and Jamie Anderson, whose precision game Tommy admired; and Davie Strath, less funereal than usual, lifting a glass. According to the

Citizen

, “The company present numbered over 100.” Heads turned as Tommy slipped between celebrants in cigar-scented air, shaking hands and patting friends’ backs under an oversized flag festooned with the club’s petaled emblem. He wore his finest suit and a pin-striped waistcoat. Dozens of lasses must have wished they could dance with him, and many would get their wish. “The thing about quadrille dancing,” one St. Andrean said, “is that you may start with your auntie, but soon you find yourself with the girl you spotted across the room. Imagine gazing at her as everyone changes partners until finally your hand is on her hand and your other hand is on her waist.”

The following week, newspapers including

The Scotsman

informed the nation that the first Rose Club Ball in old St. Andrews had been a sensation, surpassing even the annual ball of the Royal & Ancient. Only Tom Morris realized what bad news that was. Tom knew that the town’s gentleman golfers would not appreciate being upstaged by a pack of foolhardy young men.

With a population of 6,000, dwarfed by Edinburgh’s 200,000 and Glasgow’s half million, St. Andrews was a small town with the surface calm and subterranean strife of other small towns. The busybody pastor A.K.H. Boyd liked to quote a visitor who said, “Hell was a quiet and friendly place to live in, compared with St. Andrews.” Early in 1872 the town hummed with talk of the Rose Club, while Tom’s employers sat in their clubhouse muttering over the newspapers. As Tommy would have expected had he had a politic bone in his body, he and his friends had angered the men who ran the town—the R&A men who put up the money golf professionals played for and controlled the businesses Tommy’s friends hoped to enter. An apology from the Champion Golfer might have helped, but he was not sorry. It was left to Tom to spend weeks assuring his employers that the lads meant no offense. In the end, the success of the first Rose Club Ball assured that there would never be a second Rose Club Ball.

In March of 1872 a dozen golf professionals met for a stroke-play event in Musselburgh, the scene of Tom’s riotous match with Willie Park. Tommy coasted home six shots clear of Jamie Anderson and seven ahead of local heroes Park and Bob Fergusson. As the

Citizen

saw the Musselburgh tourney, “none had hitherto succeeded in anything like the steady play for three rounds now added to Young Tom’s credit.” The win added £12 to Tommy’s bankroll; his father finished eighth and won nothing. A day later Tommy teamed with Davie Strath in foursomes against Park and Fergusson. The Rose Club duo took the first of three rounds by the thinnest margin, 1-up. Tommy and Strath also won the second round by one hole, spurring Park to swing so hard in the last go-round that he

huffed

with the effort, which Tommy found funny. Willie may as well have ducked into Mrs. Forman’s Public House; the boys from St. Andrews closed out the contest on the seventh green. After that Tommy accepted one more challenge: facing Fergusson in singles. One hole down at the midpoint, out-driven on almost every hole, he rallied to beat the quiet man and went home from Park’s dunghill unstained—three wins in three tries in two days.

In April the Royal Liverpool Golf Club spent an eye-

Popping £103 to give Scotland a run for its money. The golfers of Royal Liverpool were merchants who’d made fortunes turning their rusty port city into England’s “maritime metropolis.” Now they wanted to put their club on the map by hosting the grandest professional event ever seen. Their course in Hoylake, England, was no gem, but a record-setting purse would attract what newspapers called “Scotland’s golfing celebrities.” Even then, the way to a golfer’s heart was through his pocket.

The event’s purse of £55 would more than quadruple the Open purse of £12, with £48 more paying for railway tickets and lavish dinners for the golfers—astounding luxury to professionals of Tom’s generation, who had never been treated as a club’s guests. Willie Park, Davie Strath, The Rook, and other players took fast trains south to Liverpool, where horse-drawn coaches took them across the River Mersey to the links. Spectators watched for the coach carrying the golfer one writer called “primus inter pares”—first among equals.

Stepping down from his carriage at the Royal Hotel, a stone box with the Irish Sea at its back, Tommy saw the course—a patchy waste nibbled by rabbits, with a horse-racing track running through it. He had won an informal tournament there a year before. Now he joined the other players for a long, loud dinner hosted by barkeep John Ball, whose son would win the 1890 Open. Ball kept the drinks flowing while the golfers sang and toasted bonny Scotland.

Sixteen players gathered in front of the hotel on Tuesday morning, April 25, 1872. According to a newspaper story, the Grand Professional Tournament would be “a rare treat to those who have never had an opportunity of seeing the ‘far and sure’ strokes of the leading professionals.” It would be the first major professional tournament ever held in England. Tommy teed off first, his drive sailing over a corner of the racetrack. He set off after it, trailed by more than a hundred spectators in a spitting rain.

The first hole was 440 yards of sandy turf and marshes pocked with reeds. The wooden rails of the racetrack were in play. So was the track itself: You might find your ball in a hoofprint. Tommy struck a low second shot to safe ground, knocked an iron to the green and rapped in the putt for a four. He had an edge already—nobody would beat four on that hole that day.

The second hole ran along a hedge. The racetrack’s railing cut the fairway in half. Tommy’s drive was “successful,”

The Field

reported, but his next shot “went into a ditch which caused a bad stroke.” His recovery veered out-of-bounds, and he made eight on the hole—the first sign that the champion might struggle today. One newspaper quoted him in dialect as saying it was “no’ my day oot for stealing long puts.”

Tom and Willie Park fell far behind. Bob Kirk also stumbled. In a turn of fate

The Field

called “rather unfortunate,” Kirk hit three balls out-of-bounds and made a 17 on the first hole. His 97 in the first of two rounds left him 15 strokes behind Davie Strath, whose 82 gave nervous Davie a three-shot edge on Tommy and the Rook.

By now, rain was pelting the links. The golfers waited out the downpour inside the hotel. Perhaps Tommy had a small beer with his cousin Jack, Royal Liverpool’s resident professional. This walking Jack Morris with the same name as Tommy’s crippled brother lived in a converted horse stall in the hotel’s stables. His father, George—Tommy’s uncle—had spent years living down his long-ago thrashing at Willie Park’s hands (“For the love o’ God, man, give us a half!”). In 1869 George Morris went to Hoylake with Robert Chambers, the wealthy amateur who had umpired the riotous, nullified match between Tom and Willie Park. At Hoylake, Chambers and George Morris laid out the Royal Liverpool links. It was not a task modern golfers would recognize as course design. They walked the links, picking out spots that looked like putting greens. When they found one, George cut a hole with his penknife. They left a stick or a seagull feather in the hole to show golfers where to aim.