Tommy's Honor (15 page)

Authors: Kevin Cook

Ten years before, lying on this turf after a pell-mell run down the Alps, Tommy had looked up and seen white dragons and sailing ships crossing the sky. Today they were only clouds. They were the vapor of water, as he knew from his natural philosophy classes at Ayr Academy. Clouds were the seas’ breath drawn into the sky to fall as rain that flowed through rivers and burns, mills, distilleries, and our own bodies until it found its way back to the seas. The more he knew of the world, the more he believed that a world without magic could still be full of wonders.

He turned to his father. “Far and sure, Da,” he said.

Tom nodded. “Far and sure.”

They both knew the last hole by heart: 417 paces, wind right to left, dunes to the right and Goosedubs Swamp to the left. One hole for the Belt. Tommy had the honor.

He waggled. He pulled his driver back behind his head, twisting until his left shoulder touched his chin and the driver’s shaft brushed the hairs on the back of his neck. At the top of his swing he was coiled so far to the right that he nearly lost sight of the ball. Then he uncoiled, his right elbow digging into his side, his hips and shoulders turning, pulling the clubhead through an arc that blurred into a sound.

Crack!

The ball long gone already, long and straight.

Spectators ran after it. Someone shouted that Tommy had won.

Not yet. A misfire could still cost him two or three strokes, enough to give his father a last putt to force a playoff. Tommy would win if he played the last hole the safe way, knocking a niblick to a broad part of the fairway a hundred yards short of the putting-green, then another niblick to the green, where he could take two putts, make his five and claim the Belt. But five was not a number that Tommy cared to shoot for. He had a long spoon in his hands and a flag a bit more than 200 yards away. He would try to make three.

It was all Tom could have hoped for. Not even Willie Park tried for threes when fives would win. It was a foolish choice, the only choice that could still cost Tommy the Open.

Tommy’s second shot took off on a low line, cutting through the wind. For a second it looked bound for the Goosedubs, but the ball held its line against the wind, safely to the right. It was still in the air when Tom nodded as if to say

Good for you.

Tommy’s ball was headed for the green, and the tournament was clinched. His backers shouted.

Young Morris has done it!

Young Tommy—

Tom Junior—

The boy has won!

He chipped close and made four. His third-round score was 49, yet another course record. Spectators, bettors, and golfers gathered round to see the Earl of Stair present the Belt to the new champion. Tommy held the Belt up for all to see, spurring the loudest cheers of the day.

Seventeen-year-old Tommy had smashed the Open record by eight strokes. The

Ayrshire Express

noted that “the winner of the Belt was the youngest competitor on the Links,” a distinction he won even more handily than he won the Belt, for he was the youngest by ten years. His victory made golf-watchers think Tommy might win two or three Opens in a row. Who would stop him?

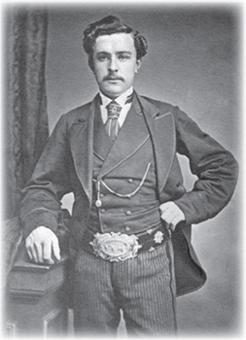

Photo 7

After winning the Open, Tommy posed in

Thomas Rodger’s studio.

T

he champion stood with his fist on his hip. While taking his pose he rustled the arras behind him, a velvet curtain meant to add a touch of theater to the photograph. Tommy Morris wore his Sunday best, all black except for a high white collar, his watch fob and the broad silver buckle of the Championship Belt. His eyes challenged the camera. He wanted the photographer to hurry up and let him go. Tommy could barely stand still for ten seconds, much less the minute it took to expose a calotype image. He was itching to

move.

Even worse than standing stock-still was holding this pose, fist on hip, as if he were some pretentious nabob. The pose was forced on him by the size of the Championship Belt—there were no clamps or notches on the Belt, which was far too big for Tommy’s thirty-inch-waist. His fist pressing the Belt to his hip was all that kept the Belt from sliding down to the floor.

He stood in a little glass house, the outdoor studio of “calotype artist” Thomas Rodger, who had built this greenhouse in the sunniest part of his garden. It was hot inside Rodger’s glass studio. The light was strong enough to show the weave of Tommy’s necktie and the texture of his thin mustache. Rodger captured the image on thick white paper coated with silver nitrate. Tommy appeared first as a pale gray ghost. Rodger washed the paper with gallic acid; the gray parts darkened and there stood the Champion Golfer of Scotland. Long before his image was fixed on paper, however, Tommy was crossing North Street on his way to the links. It was late in the forenoon and he had his own things to make: wagers, putts, money.

His era was the true dawn of professional golf. Club members still saw their medal competitions as the game’s most important events and lauded their medalists with banquets, long speeches, and innumerable toasts, but golf-watchers were increasingly drawn to the professionals, who played the game better. A new idea was afoot—the belief that there was something special about seeing the national sport played at its highest level, even if the player was not wellborn or well-to-do.

The men of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews were not above encouraging the professionals. Prestwick had stolen some of the old town’s thunder with its Open Championship, but the Open was by definition open to all golfers, amateur and professional, and by 1868 it was clear that the amateurs were overmatched. William Doleman, a Glasgow baker who was the best amateur in Scotland, led the amateurs in that year’s Open with a score of 181, a far cry from Tommy’s 154. The R&A members reasoned that if all the best golfers were professionals, a professionals-only event might help drive home St. Andrews’ claim to be golf’s capital. “[I]f not at the head quarters of the game, where can golfers expect to see the best playing?” the

Fifeshire Journal

asked.

It wouldn’t take much money. The cracks would pay their own way from one end of Scotland to the other to play for ten pounds. They groused when Prestwick cut the Open’s prize money in 1868—Tommy got only £6 for his victory, a pound less than his father had won the year before—but most of them made the trip anyway. So it was not surprising that they hustled to St. Andrews when R&A members topped the Open’s prize money at an event of their own, offering a purse of £20 with £8 for the victor. The St. Andrews Professional Tournament, conceived in 1865 and all but forgotten today, instantly became a legitimate rival to the Open.

Like bounty hunters in America’s Wild West, the crack golfers of Scotland were with few exceptions a rough-hewn, money-hungry bunch, smelling of tobacco and whisky. Two weeks after Tommy’s Open victory, they gathered in the shadow of the R&A clubhouse, where they chatted and made a few final side bets. Tommy stood at the first teeing-ground, squeezing the suede grip of his butterscotch-colored driver, waggling the club almost to the snapping point. The others, his father included, had no intention of letting this stripling pocket prize money they needed for eating, drinking, betting, and, in Tom’s case, tithing. They could not be bothered to watch Tommy slash a drive that nearly reached Swilcan Burn.

There was another young golfer on hand that morning, a tall, thin fellow of twenty-seven with a smoothly elegant swing. Davie Strath, a friend of Tommy’s who worked as a clerk in a law office, had learned the game by tagging along with his brother Andrew, the 1865 Open champion. After Andrew succeeded Tom Morris and Charlie Hunter as greenkeeper at Prestwick, Davie followed him there. In the summer of 1868 he spent long days sitting in a stiff-backed chair by Andrew’s bed, watching his tubercular brother sputter for breath, praying out loud with Andrew and praying for him when he had no breath to pray, until the merciful day when Andrew sank into his cow’s-hair mattress and lay still. He was the latest in a long line of Straths to die of consumption, and when Davie returned to St. Andrews half the town expected that his own handkerchief would soon be spotted red. Thinly handsome with dark, lustrous hair combed straight back from the widow’s peak above his high forehead, black-clad Davie often looked preoccupied, like a nervous undertaker. Even his slow backswing had a melancholy air. Like Tommy, Davie had never done much caddying. Instead he studied mathematics and bookkeeping. He was a reader, equally keen on Homer, Plato, and Archimedes. Like Tommy he believed that a professional golfer could also be a respectable young man—a radical thought that triggered golf’s first dispute over amateur status.

By entering the St. Andrews Professional Tournament in 1868, Davie Strath challenged the R&A members’ conception of the game. “It was objected to him that he was not a professional,” the

Fifeshire Journal

reported, “because he is a clerk in a lawyer’s office, and not at the call of gentleman players.” In short, he wasn’t a caddie. The men running the event still equated professionals and caddies: A professional golfer was a caddie who also played for money. Tommy had slipped through the cracks by playing for money before anyone objected, but Strath was no greenkeeper’s son. He was a law clerk with designs on middle-class respectability. Club members urged him to drop out of the tournament. They said he was risking his future if he played.

On the eve of the event, Strath was called to a meeting chaired by Major Robert Boothby and General George Moncrieff of the R&A. Boothby and Moncrieff were in a bit of a hurry, for it was the night of the club’s annual ball, a highlight of the town’s social calendar, a night of feasting, music, and dancing until dawn. They had decided “to give young David a choice,” noted the

Journal

, “either that he decline to play as a professional, or by playing on the morrow as one, elect to be regarded as a professional for ever.” The fact that Major Boothby had won £10 at an “amateur” event at Perth didn’t matter because he was already a gentleman. As Peter Lewis of the British Golf Museum puts it, the chasm between the gentry and golf professionals “was not about money in the 1860s, it was about attitude and whether someone could be conceived of as a gentleman.” Boothby and Moncrieff wanted young Strath to think twice before joining the unsavory ranks of the cracks.

Strath did not back down. “He foolishly, we think, elected to cast in his lot with the professionals,” the

Journal

sniffed. The next morning, Davie Strath sealed his fate with one of his slow, mournful backswings and a drive toward Swilcan Burn.

The eighteen-hole St. Andrews Professional Tournament of 1868 was finished before many R&A members got out of bed—“before the gentlemen awoke from the recuperative slumber of the Ball morning to the fact of the existence of a new day,” in one report. Tommy won; Strath came in fifth. Tommy’s £8 first prize, along with the £6 he won at the Open and £5 from another tournament the next week gave him £19 in prize money in less than a month—a fraction of what others had won by betting on him and perhaps less than he’d won in side bets, but a tidy sum in an era when farmhands earned £10 a year and some houses in St. Andrews still sold for £20. No one had imagined that a golfer would ever earn so much simply by swinging his sticks. Tommy was starting to think that it might be possible to do nothing else—to play a tournament or money match in one place and then move on to the next, the way play-acting troupes went from town to town.

Could a man be a touring professional golfer? That farfetched notion was much discussed at the Cross Keys Inn on Market Street, where Tommy sat by the fire nursing a pint of blackstrap, a golden mix of porter and soda water that was his father’s favorite drink. He and friends including Davie Strath and James Conacher, a fellow member of the local Young Men’s Improvement Society, gathered at the Cross Keys to celebrate Strath’s professional debut. Strath, so often nervous or morose, brightened in Tommy’s presence. They joked about certain snuff-sniffing majors and generals, ancient men who believed that no money golfer could be more than a low-living crack. Who needed the Royal and Ancient? The ambitious young men of St. Andrews could form their own club.

As tradesmen’s sons, Tommy and his friends had no hope of ever joining the R&A. Not being tradesmen themselves, they didn’t fit into the St. Andrews Golf Club, a band of plumbers, tailors, cabinetmakers, and other so-called “mechanics” who played when the R&A men were not using the links. And so in 1868 Tommy and friends banded together and gave themselves a cheeky name: the Rose Golf Club.

There was already a Thistle Club in town, named for Scotland’s national flower and dedicated to upright Scottish values. The thistle’s opposite was the rose, national symbol of England, sign of modernity and empire. In making the rose their symbol, Tommy, Strath, Conacher, and their circle were claiming to be citizens of a modern world whose capital was London, 400 miles away. They believed that Scotland should be less Scottish and more British, and might better be called North Britain. They aligned themselves with Dr. Samuel Johnson, who had written that “the best prospect a Scotsman ever sees is the high road to London.” (On a 1773 visit to St. Andrews with his Boswell, the Scotsman James Boswell, Dr. Johnson remarked on the town’s “silence and solitude of active indigence and gloomy depopulation.”) The members of the Rose Club thumbed their noses at Burns, haggis, kilts, and other things Scottish, except of course for golf, and while officially a golf club they seldom played the links as a group. More often they met to dine, drink, and debate world events into the wee hours.

The Rose Club’s emblem was as provocative as the name. Its petals suggested an aspect of female anatomy. The club members’ sexual lives were furtive at best, at least until they married, and even then the realities of sex could be a rude surprise to their brides, who were expected to be virginal until marriage. Some Scottish lasses were kept in such ignorance that they did not know where babies came from until they gave birth. Scottish lads of the time, however, were as randy as those of any country or century. The adventurous visited prostitutes in the dark corners of Edinburgh or in the fisher-folk’s quarters in St. Andrews, where a fellow could sin with a toothless woman while the salty blood-scent of herring-guts filled the room and a piglet rooted under the bed—or was it a child? Sex preoccupied the Rose Club men no less than it had moved the author of the 1819 poem “Sanctandrews,” who described girls washing clothes in Swilcan Burn, lifting their skirts to keep them dry: “Swilcan lasses clean, spreading their clothes upon the daisied lea/And skelping freely oe’r the green, with petticoats high kilted up I ween/And note of jocund ribaldry most meet; from washing-tub their limbs are seen.” Even Burns rhymed “fate” with “mate” and wished his way under his Jennie’s “petticoatie.” The Rose Club lads had no use for Burns’ rusticity but liked his honest lust.

Lacking a clubhouse, they met in pubs. They were regulars at the Criterion and the Cross Keys, where they ate lamb stew and and argued about books, politics, money, sometimes even golf. Young men born in fast-changing times, they wished they could ride the new underground railcars that crawled under London like iron moles, open carts pulled by steam engines through tunnels lit by oil lamps. The Rose Club discussed the Crown’s recent ban on public hangings in London, a law enacted not because hangings were barbaric but because they were getting too popular. The Rose Club debated the schemes of Glasgow surgeon Joseph Lister, who cleaned wounds and scalpels with carbolic acid on the theory that the acid killed “germs.” Even after Lister’s trick cut the death rate for major surgery from 50 percent to 10, surgeons scoffed when he suggested that they wash their hands between operations.

Tommy and friends sat in the flicker of a gas lamp, dipping boiled potatoes into a tee-sized mound of salt on a scarred oak table. Some drank small beer, a low-alcohol brew. Some drank blackstrap or claret. A few sipped stronger stuff. A whisky drinker might offer a toast to science, for according to Monsieur Pasteur of France it was those germs, tiny unseen creatures eating and excreting, that turned water and grain into whisky. After midnight the innkeeper would shoo the debaters through the door and the merry men of the Rose Club would spill into a darkened town, for the lamplighter had already made his last rounds, extinguishing streetlamps to save gas between midnight and dawn. They found their ways home by moonlight.

Twenty-one miles to the south, another young golfer was making his name in Musselburgh. Bob Fergusson was no debater and no drinker, but a teetotaler who rarely spoke above a whisper. Long-legged, spare, and goateed like the martyred American president Lincoln, twenty-four-year-old Fergusson was the best Musselburgh golfer to come along since Willie Park, and like Park he first attracted wide notice by challenging a famous St. Andrean.

“There was doubtless jealousy between St. Andrews and Musselburgh,” Bernard Darwin wrote, “but it seems fair to say that St. Andrews was unquestionably the metropolis of the game, where on the whole the best golf was played by the best players.” That sort of talk could get a man punched in Musselburgh, where partisan crowds hissed St. Andrews golfers and cheered their mistakes. Fergusson, though, was a gentle soul who shied from inflaming the old civic rivalry. One St. Andrean called him “uncommonly civil for a Musselburgh man.” When Fergusson issued a challenge he did it not with a newspaper ad but with a whispered suggestion followed by a handshake.