Tommy's Honor (25 page)

Authors: Kevin Cook

This was too much losing for him to stomach. Tommy challenged Willie Park to play singles for £25. Willie, never one to turn down a bet, agreed.

In the early holes the graying Park, having regained some of his old power through practice or sheer cussedness, took a two-hole advantage. But Tommy wasn’t fettered to his father as he had been in foursomes. Two down with four to play while Willie’s fanatics howled at him, he squared the match, then took the last hole and sent them shuffling home. Later that fall he faced Willie Park for another £25 at the same links, again with a raucous crowd tracking their every move. This time Park held a two-hole edge with only three to play. According to the

Fifeshire Journal

, “It was the general impression that he had the game in hand, but Young Tom made a brilliant finish, won the three holes, and gained the match by one.”

The marriage banns of Thomas Morris Junior and Margaret Drinnen were announced from the pulpit of Holy Trinity Church for three consecutive Sundays in November. The wedding was set for November 25, 1874. As tradition dictated, it would be held at the bride’s home church, the parish church in Whitburn.

It is telling that Tom did not go to Whitburn for the wedding. His wife Nancy was bedridden, but Tom could have made the trip in half a day. The fact that he missed his son’s wedding suggests his disapproval, which suggests in turn that the bride’s past was no secret to the Morrises. Tommy may have answered gossip about her by telling his parents everything. To him, Margaret was brave as well as beautiful. Their marriage would serve as a mutual rescue, with Meg saved from servitude, sin, and disrepute, and Tommy delivered from a frilly army of timid, devoutly Presbyterian piano-playing virgins.

While their parents stayed home on his wedding day, Tommy rode the train into coal country with his sister Lizzie and paraplegic brother Jack, who had to be lifted onto the train along with his trolley. It was hard work getting Jack through Whitburn’s muddy streets. He could pull himself along in the flat, dry parts, propelled by his muscled arms and gloved hands, but mud foiled him and he had to be carried—heavy work now that Jack was fifteen years old. He had to be carried up the church steps and eased into a pew, where he sat beside Tommy, across the aisle from the bride’s family. Among the Drinnens was Meg’s father Watty, turned out in his shabby Sunday best, his skin tinged with coal dust. Watty was proud of his Meg and he had a right to be, even if his pride was mixed with puzzlement, seeing his pretty daughter marrying a well-to-do lad, academy-educated—a golfer, of all things.

Lizzie Morris served as Meg’s best maid that morning. Jack, helped forward from his pew, was his brother’s best man. The service was straightforward, with the bride and groom saying their vows and the minister pronouncing them man and wife. There was no kiss. After the ceremony Tommy and Meg signed the parish register. He signed as “Thomas Morris, Golf Ball Maker, Bachelor.” She signed as “Margaret Drinnen, Domestic Servant, Spinster.” A spinster no more, she left the church as Margaret Morris, wife of the world’s best golfer. Soon she would have a respectable house and a maid of her own.

Back in St. Andrews, Tom Morris proposed a toast. A born conciliator, Tom never held a grudge in his life. What he wished above all was to keep things running: the links, the shop, and the partnership of the golfing Morrises, father and son. That partnership would last even if they disagreed on something as vital as Tommy’s choice of a wife. And so that evening, while Tommy and Meg enjoyed their first hours as husband and wife, Tom hosted a supper in Tommy’s honor at the Golf Hotel.

There were echoes here for Tom. The Golf Hotel stood on the former site of Allan Robertson’s cottage, where Tom had made featheries with Allan and Lang Willie thirty years before. Now Tommy’s Rose Club friends and Tom’s workshop employees gathered to eat, laugh, and drink to the newly weds’ health. The

Citizen

described “a substantial repast and the usual toasts being drunk,” including a toast to “the health of Tom Morris, Jun., who they must no longer call Tommy, remarking on his distinguished career as a golfer, and the many victories and trophies he had won. These marked him out as the champion pars excellence. He had carried off the ‘belt’ in three successive years against all comers notwithstanding that he was then not out of his ‘teens.’ His performance had not in the least abated as shown by his having twice this autumn defeated Willie Park…. No doubt much of his success was due to that amiability of temper, together with fixed determination, which made him so much a favourite both on and off the green, and which would be carried into the new relationship he had that day formed.” With Tom Morris and company hoisting drinks, the night careened pleasantly toward a final toast to the clubmaker’s craft and one, obligingly, to “the health of ‘The Bride.’”

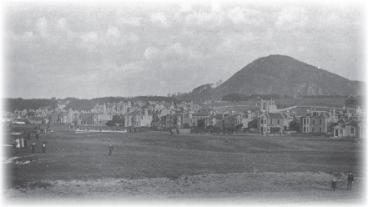

Photo 12

Tom and Tommy faced the Park brothers on the links at North Berwick, where Berwick Law looms over the town.

LEVEN

A Telegram

T

he newlyweds settled into a two-story house on Playfair Place, 200 yards from the Morris place on Pilmour Links. The rent was £27 a year. Some St. Andreans thought the house a trifle ostentatious, though Tommy could have afforded a bigger one. Without quite flaunting his money, which would be a sin in his father’s eyes, he was demonstrating his and Meg’s desire to be a respectable couple on a respectable block in old St. Andrews.

According to Rose Club member George Bruce, Tommy was “united, both in the bonds of affection and wedlock, to a young woman for whom he had the strongest love.” Meg furnished their half-dozen rooms in a style that would have suited a house in Edinburgh. As custom required she consulted Tommy’s mother before buying anything for the house, though she knew more than Nancy about fabric and furniture. Meg put up venetian blinds and tasteful wallpaper. She put a new cast-metal bed in the bedroom and stocked her well-lit kitchen with tin-lined saucepans and Staffordshire crockery. On a kitchen counter sat Mrs. Beeton—a sturdy book titled

Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management

. Isabella Beeton’s 1,014-page bible of middle-class domesticity advised Britain’s wives on everything from cooking, cleaning, making social calls, and renting a flat to whipping up a batch of homemade hair tonic. Mrs. Beeton had died in 1865 after giving birth at age twenty-eight, but her advice lived on. It was a measure of how far Margaret Morris had risen in the world that she now had her own Mrs. Beeton, a prized wedding gift.

Along with recipes for broiled partridge, stewed rabbit in milk, baked apple pudding, and 2,000 other dishes, Mrs. Beeton gave Victorian wives advice on how to hire a maid. That was a section Meg could skip. Her years at the lower end of the same transaction left her with little patience for the conventional wisdom that saw maids as lazy, though they worked up to twenty hours a day, and greedy, though they dined on table scraps and paid for the clothes they worked in. Meg hired a local girl and gave her crisp direction on cleaning, washing, dress, manners, and other matters, from walking behind the lady of the house when they went out to making sure that Tommy’s boots were clean before he went to the links to muddy them. After leading the girl to the grocer’s on Market Street to shop for sugar, tea, and peas, Meg would open wooden drawers stocked with nuts, spices, and dried fruit, each drawer holding its own strong scent. She’d leave the grocer her instructions and then off they went to the next shop, the golfer’s wife with her maid trailing behind her and whispers trailing the maid. The whispers had to do with Meg’s fast rise in status. After all, she had been a maid in this very town only months before, unable to say good morning to St. Andrews’s high-hatted matrons without giving offense, and now she walked down Market Street with her head high. On social calls she left behind a calling card with Tommy’s name on it and another with her own:

Mrs. Thomas Morris Jnr.

Meg and Tommy had to know what a stir their marriage would cause. She was no blushing bride but a test case for social mobility, a thirty-year-old from coal country. How had she landed young Tommy Morris? By being quick to lift her crinolines?

Despite the gossip, Meg did what she could to fit in. She greeted other wives in the street and spoke knowledgeably about the latest fashions from London and the Continent when someone stopped to chat. Tommy’s sister Lizzie became a particular friend. Lizzie, who had begun taking chaperoned walks with a Rose Club member named James Hunter, may have joined Meg and other women in one of the town’s more comical social experiments, the Flagpole Curriculum.

The well-meaning wives of several R&A members wanted to teach the youngest caddies to read and do figures. That way the boys might rise above their illiterate fathers. After recruiting young women like Meg to be teachers, the R&A wives convened early-morning lessons at the flagpole beside the R&A clubhouse. To keep the lads alert, the ladies served coffee. Unfortunately, the coffee was a stronger diuretic than the tea that the boys were accustomed to drinking. They were willing to learn, but their bladders were weak. To the ladies’ horror and Meg’s likely amusement, the boys put the flagpole to what was delicately termed “an ignoble purpose.” They peed on the flagpole, then ran like collies, and that spelled the end of reading lessons by the links.

On Sundays, when the links were closed by order of Tom Morris, drums called the town to worship at half past ten. Tommy and Meg, looking stylish but not showy, linked arms and walked up North Street toward the seven-story tower of Holy Trinity Church. The tower, which predated the rest of the church, had been eighty years old when Columbus sailed from Spain in 1492 and had served for centuries as a prison for women found guilty of fornication. It held relics including the Bishop’s Brank, an iron cage that fit over the head of a too-talkative woman, with an iron tongue that fit over her tongue, keeping her quiet. Pastor Boyd may have wished he could apply such discipline to his chatty flock, now filling the pews under Holy Trinity’s wide stone arches. A thousand was a middling turnout in St. Andrews, a devout town in which the

Citizen

chided those who missed Sunday services. The congregation generated enough body heat to warm the coldest Sabbath, while in the summer parishioners carried poseys to ward off the thickening scent of all those bodies.

The Reverend Andrew Kennedy Hutchison Boyd, known as A.K.H.B., was a plump pumpkin of a man, the author of the popular

The Recreations of a Country Parson

, as well as

Twenty-Five Years of St. Andrews.

Boyd was a favored dinner-party guest in Edinburgh and London, where he spoke of his life in the provinces. When A.K.H.B. visited the capitals he left a substitute to preside over services at Holy Trinity. It happened so often that some St. Andreans registered their disapproval by staying home on Sundays. For this they were belittled in the pastor’s memoir. “Scotch-fashion, two or three persons of humble estate had informed me that they disapproved of Stanley’s preaching for me,” he wrote, “and they ‘testified’ by staying away from service. Of course, nobody missed them.” After one trip Boyd returned to find a clutch of canes hanging from his doorknob, a reminder that he did as much traveling as preaching. Stepping up into his stone pulpit that Sunday, black-robed and orange-cheeked, he joked sourly that he now had the best walking-stick collection in town. Then came a shout: “Ye’ll not put

that

in your books!” The parishioner was right. In his memoirs, at least, A.K.H.B. got the last word.

In church, Tommy and Meg mingled with local swells and their wives, professors from the university, bankers, butchers, and bakers; the coal-pit bottomer’s daughter worshipped within sniffing distance of R&A members. With God’s eyes on them, better-born townspeople were likely to be cordial. “Tommy, I hear you’ve a match coming up,” a gentleman might say. “You’re in fine form. We must have you and your wife for tea.” Yet no invitation to tea would follow. Tommy was no more welcome in a gentleman’s parlor than Meg would be in the sewing circle of the gentleman’s wife.

Tommy still had his Rose Club allies. The lack of an annual ball hadn’t kept the Rose Club from “flourishing,” according to the

Citizen

, “yearly adding to its membership and popularity.” In March of 1875 the Rose Club’s James Hunter married Lizzie Morris at Holy Trinity Church. Tom Morris, who had passed up Tommy and Meg’s wedding, was delighted to attend this one along with the rest of his family. Hunter was a favorite of all the Morrises, a bright young businessman who had made a fortune in timber. After an 1865 fire ignited fifty tons of Civil War gunpowder and leveled much of Savannah, Georgia, Hunter sailed to America and helped rebuild the town. Tom was thrilled to see his only daughter wed such a clever and prosperous young merchant. He joked that he and Hunter were in the same business: turning sticks of wood into money.

Hunter repaid Tom’s regard for him. As part of his wedding-night revels he threw a party for his new father-in-law and Tom’s club-makers. “On Thursday evening last week,” the

Citizen

reported, “the workmen in the employment of Mr. Thomas Morris were entertained along with a few friends to supper in the Golf Hotel (George Honeyman’s) by Mr. Hunter on the occasion of his marriage with Miss Morris. Among a variety of suitable toasts ‘The Newly-Wed Pair’ was pledged.” James Hunter would be the Morrises’ financial bulwark from this time forward, transforming Lizzie from greenkeeper’s daughter to rich man’s wife, paying for a new gravel path for Jack to ride from the Morris house to the workshop, easing Tom’s lifelong fear of going broke.

The summer of 1875 was a season of wonders. In August a Royal Navy captain, Matthew Webb, smeared himself with porpoise fat, dove from Dover’s Admiralty Pier and swam across the English Channel in twenty-two hours. That same summer the R&A rejoiced at word that Prince Leopold had agreed to be the club’s next captain. The following year the prince himself would stand waiting while Tom Morris teed him up, then drive himself into office with a royal cannon boom. Take that, Perth and Prestwick and Musselburgh! There was no longer any doubt as to which club was the hub of golf, which town the game’s true home.

Summer also brought Lammas Fair. A throwback to medieval times, the fair began as a feeing bazaar: Men from the countryside would come to town, offering their labor to landowners who needed help at harvest time. The men signaled their availability by walking with pieces of straw in their mouths. By the nineteenth century, Lammas Fair had become a summer festival featuring gypsy caravans, music, dancing, sweet treats, and free-flowing beer. A confectioner’s stall held rows of pink sugar hearts, gifts for a young husband to offer his wife in exchange for a kiss. Tommy and Meg strolled past jugglers, acrobats, contortionists, and dancing monkeys. Perhaps they had their fortunes told in the tent emblazoned

GYPSY QUEEN.

If the palm-reader was cunning she foretold a happy event—a child coming to the young couple. A baby boy. There was no magic to this. The uncorseted middle under Meg’s dress gave her pregnancy away, and predicting a male child was just good business, a way to snag an extra coin from the happy parents-to-be. A son was said to be a “double blessing.” The customary gift to new parents was a bottle of whisky if the child was a girl, and if the child was a boy, two bottles.

When the Park brothers offered to renew hostilities at North Berwick, Tom welcomed the challenge. There was a tournament coming up in North Berwick on the third of September; he agreed to a foursomes match for £25 to be played the following day. Tommy promised to partner his father in the match. For him it was one contest among many, but for Tom another shot at Willie and Mungo Park was a chance to restore his good name. The Parks’ supporters claimed that Musselburgh ruled the world in foursomes thanks to Willie and Mungo’s victory the previous fall, a win they owed to Tom’s horrid putting. Tom knew that golf watchers were calling him a liability in foursomes, a drag on his son. He knew they said Tommy and Davie Strath made a well-nigh unbeatable duo, while Tommy and Tom were well beatable. Bettors made Tommy and Strath heavy favorites in any match they played, but the two Morrises were often underdogs. And like many an aging athlete, Tom was driven to prove his doubters wrong. He was sure he could play as well as ever on a given day. All he needed was the chance. All he needed was the day.

He needed the money, too. Not to live or even prosper—son-in-law Hunter had eased the fear of penury that spurred men of Tom’s generation—but to measure his success or failure. For despite his progress in the world, Tom was still a crack at heart. He was a gambler, and like most gamblers he knew exactly how his wagers stood. He and Tommy were £25 down to the Parks after losing the previous fall. Tom looked forward to September with a gambler’s hunger to get even.

But Tommy was torn. The timing was wrong. Meg was now in her ninth month of pregnancy. Her belly was big and tight as a drum, with the occasional drumbeat from inside. The portly town midwife, nicknamed Clootie Dumpling, said Meg’s time was at hand. Meg was nearing her confinement, when men were banished while females boiled water, gathered up linens, and enacted the bloody drama of childbirth. There had been progress during midwife Clootie Dumpling’s time: By 1875 only five women died for every thousand live births. Yet labor and its aftermath, when infections took many more lives, were fearful events. As one writer observed, “these times are looked forward to with dread by all young wives.”

There is no reason to think Tommy was any more inclined to witness childbirth than any other Victorian man. His view would have matched that of Kipling, who wrote, “We asked no social questions, we pumped no hidden shame, we never talked obstetrics when the Little Stranger came.” But Tommy was unusually devoted to his wife, whom he showed what Pastor Boyd called “the strongest possible affection.” Tommy wanted to be with Meg at the onset of her confinement, before she was shrouded in female commotion. He wanted to be there to see her afterward, to embrace his wife and greet the Little Stranger the two of them had made.

The North Berwick tournament and the foursomes match to follow would take him away for three days. But he could always hurry home if needed. Meg may have encouraged her husband to go, placing his hand on her belly and saying, “Go on. You’ve done your part here.” Still it was Tommy’s choice. He chose to honor his pledge to his father.

The journey took more than six hours. The Morris men—“sire and son,” newspapers called them—rode the train from St. Andrews to Leuchars, changing there to a train that huffed between fields dotted with sheep. Tom and Tommy caught a ferry at Burntisland, a loud ferry packed elbow-to-elbow with travelers, many heading for North Berwick to see the golf. An Englishman making the trip wrote of being “hurried with a crowd of cheap excursionists into the ferry boat…the screams of babies and the notes of bagpipe, fiddle and other Scotch musical weapons.” They crossed the Firth of Forth to Granton and boarded a train that rattled into Edinburgh’s Waverly Station, where they switched to an eastbound train that rolled past Holyrood Palace and the rugged brown-green cliff called Arthur’s Seat, through humpbacked fields of turnips to the end of the line.