Tommy's Honor (28 page)

Authors: Kevin Cook

“I’ll play,” Tommy said.

In

The Field

’s account he “waived his objections, and, under a protest from the umpire, who gave it as his opinion that it was not weather for golf, the match was at once proceeded with.”

Why play on frozen links with bunkers full of snow? According to George Bruce, Tommy felt a duty to friends who had bet on him and who would lose their money if he quit: “He repeatedly remarked to his friends and backers that but for them he would not have continued.”

Even with Tom’s workmen shoveling and sweeping, the greens were unputtable. The players chipped on and then chipped their “putts,” trying to flip their gutties into the hole as if they were stymied. That should have given Tommy an edge, but he lost the third hole when Molesworth’s long chip bounced into the cup. The challenger had his own misfortune at the next, the Ginger Beer Hole, where his tee shot found a patch of snow “and in driving out the ball split.” It was hard enough hitting a frozen gutty that stung your hands with every full swing; worse to try chipping and putting with two-thirds of a ball.

“The next hole was played amid a blinding shower of snow. Mr. Molesworth’s ball was buried in a snowdrift, and it took him two to get out; but Tom being short in putting, the hole was halved.” This was comedy, but Tommy looked heart-sick. Reaching for the lump of pine tar in his pocket, trying to keep his hands on the club as he swung, he was on his way to a score of 112, thirty-five strokes over his course record. Molesworth was struggling even more, falling thirteen holes behind, but Tommy seemed not to notice. “His heart was not in the game,” Tulloch wrote. “It was, indeed, not very far away—in the snow-clad grave in the old cathedral churchyard, where his wife and baby had been so lately laid.”

Molesworth’s best hope was that Tommy would collapse, as he had in his last foursomes match, or simply give up and leave the challenger to claim the stakes. Instead, Tommy rallied. To his friends it seemed he was emerging from shadows, regaining his powers. On Wednesday the eighth of December he and Davie Strath made their way to the first hole through ranks of applauding spectators wrapped in wool scarves and fur hats. The novelty of watching golf in curling weather had attracted such a teeming, avid crowd that the umpire called for a rope, another of the game’s first gallery ropes, “to prevent crushing.”

Strath, lugging Tommy’s clubs to the Eden and back, did his best to help his friend through the last two rounds. He urged Tommy on. He picked Tommy’s ball from the hole, teed it up, and handed over a driver that Tommy swung without a word. They were in accord now, dead-set on finishing, snow and ice be damned. “The snow still covered the green,”

The Field

noted, “and frost being very heavy the play, especially putting, was rendered even worse than on the previous day.” Molesworth’s handicap stroke got him a hole at the long Hole o’ Cross, where both players made nine, but he lost the High Hole when his drive hopped into “long grass and snow, where he lost two strokes, and his fourth landed deep in a bunker among snow, and it took another two strokes to get the ball fairly

en route

to the hole.”

Tommy had one burst of brilliance left. He took the short tenth and treacherous eleventh “with four and three respectively, play which could not be excelled even with the green in its best condition.” The long trudge ended on the eighth hole of that day’s afternoon round, the 206th hole of the match. By then the greens had thawed. Tommy fired a 150-yard bolt to the Short Hole green and banged in the putt for a deuce on a day when other holes were won with sevens. His backers hooted and shook their fists. What a finish! The last hole of the year’s last match was vintage Tommy—perfectly played.

All evening his friends drank to his victory and his health. Tommy drank and smiled but seemed not much more festive than Davie at his most sepulchral. He had hit some clever shots and felt some delight in doing that, even now. But what he felt most of all was cold. He was spent.

“After the match,” Tulloch wrote, “he continued to be seen on the links and in his old haunts, looking ill and depressed.” Those who loved him worried that Tommy had risked his health by playing for a solid week in bone-chilling cold. But later in December he showed new signs of life. Instead of drinking alone he would meet his brother-in-law James Hunter, Davie Strath, George Bruce, and other Rose Club members for dinner at the Criterion or the Cross Keys. He ate boiled beef and potatoes, showing an appetite that heartened his friends. This rally was in character, they thought. On or off the course, in sickness or health, Tommy’s spirit rose to the occasion.

Just before Christmas he spent two days in Edinburgh. Returning to St. Andrews in time to take communion during Watch Night services on Christmas Eve, he met his hometown companions for a late dinner. Perhaps Hunter or Bruce offered a holiday toast to the coming year of 1876. It would have been a muted toast, spoken softly, all of them mindful of Tommy’s regrets.

It was near eleven when Tommy came through his father’s front door that night, bringing the cold in with him. He went to look in on his mother and found her awake. Nancy, now sixty years old, was so ill with back and stomach ailments that she struggled to sit up in bed. Still she brightened at the sight of her eldest, her “extra gift from God” grown up into a man. Tommy sat and talked with her for a time before going upstairs to his bed. A few minutes later his father poked his head into Tommy’s room to say goodnight. Then Tom made his way around the quiet house, snuffing out the last lamps, and the Morris place was dark until morning.

Tom was up early as always. Soon the fire was lit, a tea-kettle whistling. He and Nancy had their breakfast. So did Jimmy and Jack. An hour passed and Tommy still hadn’t appeared, so Tom went upstairs to wake him.

Tommy was still in bed. His father stood beside the bed, gazing down at his son’s handsome face, as peaceful as if Tommy were in dreamless sleep. There was a spot of blood at one corner of his mouth.

“On the morning of Christmas-Day they found him dead in his bed,” Pastor Boyd recalled, “and so Tommy and his poor young wife were not long divided.”

The

Citizen

was blunter: “Retiring a little after eleven o’clock on Friday evening, he was found in bed next morning a lifeless corpse. A little blood had oozed from his mouth, and the doctor who was called said that death had resulted from internal hemorrhage.”

Tommy Morris was twenty-four years old.

Generations of Scots have claimed that Young Tom Morris died of a broken heart. “It makes a nice story, but it is shite,” says David Malcolm of St. Andrews, who is a surgeon as well as a golf historian. “He died of a pulmonary embolism due to an inherited weakness. He could have gone at any time.” And yet Tommy died at a particular time, three months after sailing home too late to be with his wife as she died in childbirth, three months in which he drank more than he had before, walked St. Andrews’ cold streets late at night and played a week-long, two-hundred-hole match through a snowstorm. Grief, drink, and the cold may have weakened him until his pulmonary artery ruptured, filling his lungs with blood, drowning him in his sleep.

“The news spread like wild-fire over the links and in the city,” Tulloch wrote. “Christmas greetings were checked on the lips by the question, ‘Have you heard the news? Young Tommy is dead!’ or the whispered, ‘It can’t be true, is it, that Tommy was found dead in bed this morning?’”

Now it was Tom who was stricken. When John Sorley, the town registrar, came around with the death registry it was Jimmy, not his father, who signed on the family’s behalf. The census of 1871 had identified Tommy as “Champion Golfer of Scotland”; the death register of 1875 cast him as “Thomas Morris, Widower.” And now his father had a new round of funeral arrangements to make. Most woeful of all was the chesting service on the Tuesday after Christmas. Friends and relatives gathered in Tom’s parlor to talk and pray over legs of lamb and glasses of claret. They wrapped Tommy’s body in a pure white linen mort cloth. Then Tommy rode the men’s hands, including his father’s callused, wavering hands, into his coffin. After a last prayer they screwed the coffin shut. They buried him the next day.

“I have a picture in my mind of the popular young Tom,” the golfer Edward Blackwell wrote of his youth in St. Andrews. “I remember, too, his sad and sudden death, the gloom it cast over St. Andrews, and in some respects the most imposing funeral that has ever taken place at St. Andrews.”

Tom Morris, who never wasted a penny in his long life, spent more than £100 to bury his son. He hired a gleaming hearse pulled by black horses festooned with long black ostrich feathers. Top-hatted attendants in silk scarves walked ahead of the hearse as it carried Tommy to the Cathedral cemetery. Half the town followed the hearse. The cortege was headed by black-clad Morris men: Tom, Jimmy, and sixteen-year-old Jack, pulling himself down South Street in his Sunday-best suit. Tommy’s brother-in-law James Hunter was there along with other Rose Club members, R&A gentlemen, professional golfers, caddies, fisher-folk, and hundreds of others, many carrying wreaths of evergreens and artificial flowers. Scottish families had been ruined by less lavish rites, and Tom would soon turn to Hunter for a £200 loan. But in these last bitter hours of 1875 Tom was determined to give his son a champion’s funeral, a farewell that their town would never forget.

“The remains of poor Tommy were yesterday followed to the grave by a large cortege of persons from all quarters,” the

Citizen

reported on December 30, “and the city, usually dull at this season, wore its gloomiest as the mournful procession deployed through the streets.” At the cemetery, where the Morris plot had been dug up yet again, Pastor Boyd prayed over Tommy’s coffin and spoke of resurrection. Tom watched as the coffin was lowered into the grave that held Tommy’s wife and stillborn child and, below them, the bones of Wee Tom, buried twenty-five years earlier.

For months afterward, Tom wore a black armband to show that he was in mourning for Tommy. On Sundays, when he kept the links closed and spent much of the day in church, he wore the armband over the sleeve of his tweed jacket while performing his duties as a church elder. One of his duties was to pass around the money bag that functioned as a collection plate. Another was to hear parishioners’ confessions, and it is fair to ask whether Tom second-guessed himself while listening to the Sunday whispers of truants, blasphemers, and impure thinkers. Did Tom Morris feel that he too had something to repent?

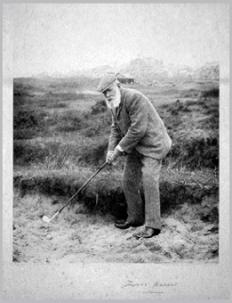

Photo 14

An autographed photo of Tom in his seventies, his shoes shiny even in a bunker.

HIRTEEN

Grand Old Man

A

quarter of a century is a very little thing in this city’s thousand years,” wrote Pastor Boyd in

Twenty-Five Years of St. Andrews

, “but it is a great thing, and a long time, to us who have lived through it. It has changed those who survive.”

During Tommy’s lifetime, the most pivotal quarter-century in golf history, Tom Morris became the first true golf professional and Tommy became the game’s leading man. Now that time was past and Tom, walking uphill from the cemetery, felt the weight of his fifty-four years. He was often quoted in dialect in those days, once by an English writer who heard the mourning father say of Tommy’s death, “It was like as if ma vera sowle was a’thegither gane oot o’ me.”

Did Tom regret letting the North Berwick match go on while Margaret died? If so, he took solace in his faith.

Thy will be done

. And there was at last some good news for the Morrises in the first months of 1876. Lizzie was expecting a baby. Perhaps Tom would have a grandchild after all. He felt a pang when Lizzie sailed with her husband to America, but in March he received a telegram announcing the birth of his grandson, born to Lizzie and James Hunter in Darien, Georgia. They named their child Tommy Morris Hunter.

Lizzie’s son was never healthy. The baby died in May, only two months old. This news was another blow to Tom, but he carried on. What else could he do? Each morning he changed into his swimming long johns. He padded out to the dunes, hung his jacket with its black armband on a whin bush, steeled himself and waded into the bay, which was icy in May, merely frosty in June. After his dip he dried off, dressed for work, and spent another day supervising workmen (“More sand!”), inspecting caddies, tapping the club secretary’s window, replacing divots (a visitor was amazed to see the great man “taking up bits of cruelly cut turf and placing them in blank spaces with a press of his foot”), and partnering R&A golfers as if his soul were intact.

Tom played a leading role that fall when Prince Leopold drove himself in as captain of the R&A. This was the Royal and Ancient Golf Club’s proudest moment, the first royal visit to St. Andrews in more than 200 years. Crowds surged toward the prince’s royal railcar at every stop it made on its journey east through Fife; in one village a thousand people turned out to see the train speed by without stopping. On the night of the prince’s arrival in St. Andrews, townspeople lit every lamp in every building, giving the town a glow that outshone the half-moon that came out that night. At eight the next morning the hemophiliac prince, surrounded by his fretful retinue, stepped from his carriage to the first teeing-ground. Prince Leopold was terrified. How could he hit a golf ball with so many of his subjects watching—and so many caddies, hoping to grab the royal gutty, crowding so close to the tee? The greenkeeper came to his rescue. Tom Morris bowed, tipping his cap, and encouraged His Royal Highness to take a smooth, steady swing with his eye fixed on the ball. Tom teed up a ball, using a bit more sand than usual to add height to the shot. Prince Leopold waggled. He swung, the cannon sounded and the ball sailed over all the caddies—a drive worthy of the crowd’s delighted applause.

The prince blinked. “How was that done, Tom?” he asked. “I never got the ball off the ground before.” After luncheon and a fox hunt, he and Tom beat two R&A golfers in a six-hole match. In the gallery stood a dark-haired woman who had come from Oxford to see her friend the prince: twenty-three-year-old Alice Liddell, for whom Lewis Carroll had written

Alice in Wonderland

.

Later that week came the second Open ever held at St. Andrews. Davie Strath led for most of the day and had the Claret Jug within reach as he played the Road Hole. Unluckily for him, the R&A had failed to reserve the links for the tournament, leaving the professionals to share the course with the usual foursomes of gentleman golfers. Playing the Road Hole in semidarkness at the end of a long, slow round, Strath saw a crowd around the green. Spectators, he thought. He let fly and watched his approach shot bean a local upholsterer named Hutton who was lining up a putt. Mister Hutton keeled over as if he’d been shot. He was still rubbing his head as Strath, shaken, putted out for a six, which he followed with another six on the Home Hole to tie Bob Martin for first place in the Open. But tournament officials questioned Strath’s score. He may have played out of turn, they said, and skulling Mr. Hutton may have kept his ball on the green and saved him a stroke. If he won his playoff with Martin tomorrow morning, they said, they might still disqualify him.

Strath, who had defied another red-coated committee on the day he declared himself a professional, refused to play under such a threat. “Settle it now or I won’t be here in the morning,” he said. The officials refused, Davie stuck to his word, and Martin claimed the Claret Jug by walking the course the next morning.

Tom Morris came in fourth, his best Open finish since 1872, and then went home to help tend his wife in the gray stone house at 6 Pilmour Links Road. Nancy, sixty-one years old, was in constant pain. A white bedpan called a “slipper” was a boon to her. The slipper was a ceramic wedge that slid under a patient who could not sit up. Nancy lamented her aches and the indignity of using such a thing. She lamented the loss of her children and grandchildren, and on the first of November, 1876, All Saints’ Day, she “joined them in heaven,” as Pastor Boyd put it, leaving Tom to arrange yet another Morris funeral. After which, as before, he returned to his duties in his shop and on the links. Old Tom was a marvel, people said. In little more than a year he had buried Tommy, Tommy’s wife and their stillborn son, grandson Tommy Morris Hunter, and now Nancy. Five dead and Tom still standing. When a writer asked about the cause of Tommy’s death, Tom said he didn’t believe that grief could kill a man. “People say Tommy died of a broken heart,” he said, “but if that was true, I wouldn’t be here.”

Two Septembers later Tom, Jimmy, and several hundred others gathered around the Morris plot in the Cathedral cemetery. Sixty Scottish and English golf societies had taken up a collection to pay for a Tommy Morris monument in the cemetery. It was a sign of golf’s growing importance that a representative of the Crown, John Inglis, Lord Justice General of Scotland, presided over the unveiling. The monument, which still stands in the south wall of the churchyard, shows Tommy in his tweeds and his Balmoral bonnet, preparing to drive a ball over the cemetery to the sea. “In memory of ‘Tommy,’ son of Thomas Morris,” reads the plaque at his feet. “Deeply regretted by numerous friends and all golfers, he thrice in succession won the Championship Belt and held it without envy, his many amiable qualities being no less acknowledged than his golfing achievements.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” said Inglis, addressing the somber gallery standing four-deep around him, “we are met to inaugurate a monument to the memory of the late Tommy Morris, younger.” With that the Lord Justice General nodded toward the honoree’s father. “You will allow me to say that we have some consolation still, for we still have a Tom Morris left—Old Tom—and I may venture to say that there is life in that old dog yet.”

After Tommy died, Tom cut back on the money matches he had lived for. He devoted more time to promoting golf and making sure that golfers remembered what Tommy had done. Tom went on to lay out more than sixty courses, including County Down, Dornoch, Macrihanish, and Muirfield. Building a course—clearing whins, digging and filling bunkers, turfing greens—could cost £100 to £300, but Tom’s fee for designing one never varied: He charged £1 per day, often completing his work in a single day. And wherever he went in Scotland, England, Ireland, and Wales, he spun tales of his famous son.

Old Tom’s rustic charm played well on the road. After hiking some barren, windburned heath for half an hour he would turn to his hosts and say, “Surely Providence meant this to be a golf links.” Each course he laid out was “the finest in the kingdom, second only to St. Andrews,” at least until he laid out the next one. Tom showed novice greenkeepers how to top-dress and rake putting-greens. He pioneered inland golf by introducing horse-drawn mowers for fairways and push-mowers for greens. Beyond that his work as a course-maker consisted largely of walking and pointing. “Put a hole here. Put another over there,” he would say, leaving plenty of time for a free lunch before he headed back to the railway station. If he stayed all day it was often to be feted as a visiting dignitary. After a singer serenaded him at one lavish dinner, Tom said, “I did no’ think much of her diction.” No one had the heart to tell him she’d been singing in French.

Still the old greenkeeper was sly enough to have some fun with an Englishman who saw him rolling putts one day.

“What! Do you play the game?” the man said.

“Oh, aye,” said Tom Morris. “I’ve tried it once or twice.”

In 1886 Tom went to Dornoch, in the Highlands 110 miles north of St. Andrews, a cold whisper from the Arctic Circle, to extend the links there to eighteen holes. The Dornoch Golf Club’s junior champion was a boy named Donald Ross, a carpenter’s apprentice who tagged along while the old man hiked the dunes overlooking Dornoch Firth. Five years later Ross left home to work for Tom at St. Andrews. He may have helped Tom build a new course on the ancient links there. Called simply the New Course, Tom’s layout was in some ways better than the original, which has been known ever since as the Old Course. Ross returned to Dornoch for a stint as the club’s greenkeeper before moving to America in 1899, his head full of pictures of Tom’s links: elevated greens; grassy hollows and hungry bunkers; subtle deceptions that rewarded local knowledge. Over the next half-century he would design Pinehurst #2, Seminole, Oak Hill, Oakland Hills, and the more than 500 other courses that made Donald Ross the most important golf-course architect of all. Even if Tom Morris had never seen Prestwick or planted a flag at County Down, his influence on Ross would still make him a crucial figure in the game’s evolution. But Ross was only one of his disciples. Charles Blair Macdonald kept a locker in Tom’s shop before he crossed the Atlantic to build America’s first eighteen-hole course at the Chicago Golf Club and lay out the National Golf Links of America, a bit of Scotland in Southampton, New York. Alister Mackenzie studied Tom’s handiwork before designing Cypress Point in California, Royal Melbourne in Australia and, with Bobby Jones, Augusta National; Mackenzie titled his book on course design

The Spirit of St. Andrews

. Albert Tillinghast, who learned the game from Tom, went on to lay out Baltusrol, Bethpage, and Winged Foot. Harry Colt, who spent boyhood summers at St. Andrews, improved Tom’s Muirfield links before working with the American George Crump to fashion Pine Valley, a course many regard as the world’s finest. In the last analysis Tom Morris’s chief contribution to the game may have been in course design, a multibillion-dollar business that grew from the barrow, spade, and shovel he used at Prestwick and St. Andrews.

Not far from Alister Mackenzie’s locker in Tom’s workshop was another wooden locker, a relic that held Tommy’s clubs and club-making tools. “Undisturbed since he last touched it,” Tom often said. But he often disturbed it. While showing a visitor around the shop, filling the fellow’s ears with well-worn stories, Tom would open the locker and pluck out a club. “Tommy’s last putter,” he would call it, or “Tommy’s last niblick,” placing the stick in the visitor’s hand. “Take it—keep it.” Of course his workshop turned out putters and niblicks by the gross; this so-called relic, part of a growing supply of “Tommy’s last clubs,” could be replaced tomorrow. Cynics would call him a showboat, but Tom knew that every golfer who left with one of those clubs would spread the gospel of Tommy Morris.

Tom surprised himself by playing better as his beard turned white. He couldn’t drive the ball 180 yards anymore, or even 150—“I can no’ get through the ball,” he told Andra Kirkaldy—but his yips disappeared. Tom Morris was now the maker of short putts. “I never miss them now,” he said. After winning a tournament at Hoylake he celebrated his sixty-fourth birthday by shooting 81 at St. Andrews, only four strokes off Tommy’s famous course record. He did it with ten 5s, seven 4s and a trey—the only time Tom ever went around the old links without a 6 on his card. “No’ that ill for an old horse!” he crowed.

By then Old Tom had another nickname. He was golf’s “G.O.M.,” short for “grand old man.” The term was borrowed from Prime Minister William Gladstone, the original G.O.M. (whose rival Disraeli said the letters stood for “God’s only mistake”). Twelve years younger than Gladstone, Tom was no less grand to golfers, though his latest honorific puzzled one grumpy old Musselburgher. The aging, ailing Willie Park had outplayed Tom through most of their careers only to see his rival hailed as the game’s patron saint.

In 1879, at a tournament in haunted North Berwick, Tom and Willie had finished far behind younger professionals while drawing the day’s biggest crowds. Three years later Tom did his fellow warhorse a favor: He agreed to play Park for £200. Tom was sixty years old, Park was forty-nine. Their last battle was, in effect, the first senior golf event. “No match of recent years has created anything like the excitement attaching to this,” proclaimed

The Field.

Tom, who had little to gain, made the match because it would bring Willie one last week of headlines as well as a hefty fee. Still Tom’s sympathy ended at the first teeing-ground. With more than a thousand spectators following the match, he stung the hole with sharp short putts and beat Park by four.

Soon a man whose sole vice was his briar pipe saw his photograph on cigarette packages. Pictures of Tom Morris seemed to be everywhere. Thomas Rodger, the calotype artist who had photographed Tommy in the Championship Belt, superimposed an image of Tom over an image of a river to make a postcard showing Old Tom Morris “walking on water.” Tom wanted no part of such blasphemy, but the card was a bestseller.