Trout Fishing in America (11 page)

Read Trout Fishing in America Online

Authors: Richard Brautigan

I'd chop wood for her stove. She cooked on a woodstove and heated the place during the winter with a huge wood furnace that she manned like the captain of a submarine in a dark basement ocean during the winter.

In the summer I'd throw endless cords of wood into her basement until I was silly in the head and everything looked like wood, even clouds in the sky and cars parked on the street and cats.

There were dozens of little tiny things that I did for her. Find a lost screwdriver, lost in 1911. Pick her a pan full of pie cherries in the spring, and pick the rest of the cherries on the tree for myself. Prune those goofy, at best half-assed trees in the backyard. The ones that grew beside an old pile of lumber. Weed.

One early autumn day she loaned me to the woman next door and I fixed a small leak in the roof of her woodshed. The woman gave me a dollar tip, and I said thank you, and the next time it rained, all the newspapers she had been saving for seventeen years to start fires with got soaking wet. From then on out I received a sour look every time I passed her house. I was lucky I wasn't lynched.

I didn't work for the old lady in the winter. I'd finish the year by the last of October, raking up leaves or something or transporting the last muttering gartersnake to winter quarters in the old ladies' toothbrush Valhalla across the street.

Then she'd call me on the telephone in the spring. I would always be surprised to hear her little voice, surprised that she was still alive. I'd get on my horse and go out to her place and the whole thing would begin again and I'd make a few bucks and stroke the sun-warmed fur of her stuffed dog.

One spring day she had me ascend to the attic and clean up some boxes of stuff and throw out some stuff and put some stuff back into its imaginary proper place.

I was up there all alone for three hours. It was my first time up there and my last, thank God. The attic was stuffed to the gills with stuff.

Everything that's old in this world was up there. I spent most of my time just looking around.

An old trunk caught my eye. I unstrapped the straps, unclicked the various clickers and opened the God-damn thing. It was stuffed with old fishing tackle. There were old rods and reels and lines and boots and creels and there was a metal box full of flies and lures and hooks.

Some of the hooks still had worms on them. The worms were years and decades old and petrified to the hooks. The worms were now as much a part of the hooks as the metal itself.

There was some old Trout Fishing in America armor in the trunk and beside a weather-beaten fishing helmet, I saw an old diary. I opened the diary to the first page and it said:

Â

The Trout Fishing Diary of Alonso Hagen

Â

It seemed to me that was the name of the old lady's brother who had died of a strange ailment in his youth, a thing I found out by keeping my ears open and looking at a large photograph

prominently displayed in her front room.

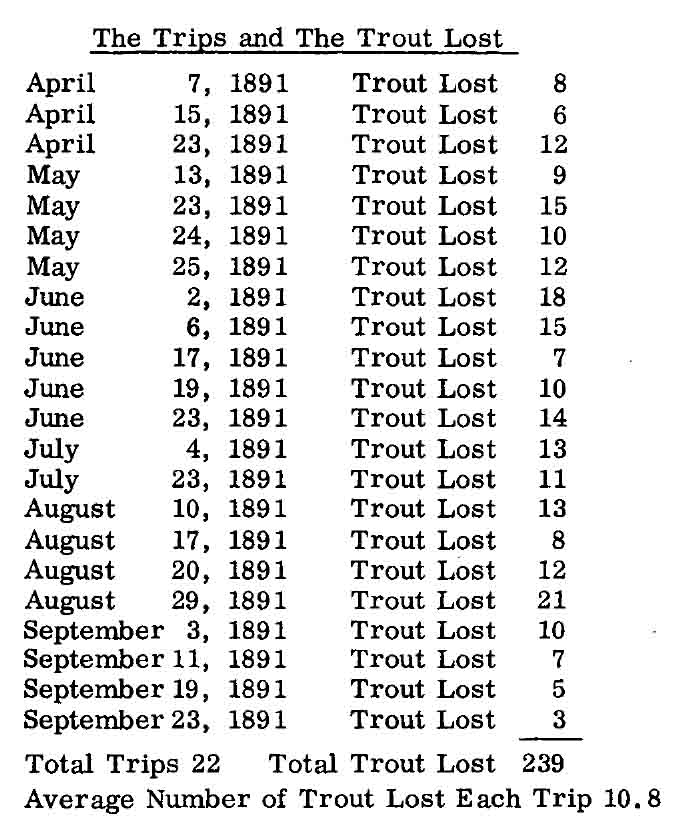

I turned to the next page in the old diary and it had in columns:

Â

Â

I turned to the third page and it was just like the preceding page except the year was 1892 and Alonso Hagen went on 24 trips and lost 317 trout for an average of 13.2 trout lost each trip.

The next page was 1893 and the totals were 33 trips and 480 trout lost for an average of 14. 5 trout lost each trip.

The next page was 1894. He went on 27 trips, lost 349 trout for an average of 12.9 trout lost each trip.

The next page was 1895. He went on 41 trips, lost 730 trout for an average of 17.8 trout lost each trip.

The next page was 1896. Alonso Hagen only went out 12

times and lost 115 trout for an average of 9.5 trout lost each trip.

The next page was 1897. He went on one trip and lost one trout for an average of one trout lost for one trip.

The last page of the diary was the grand totals for the years running from 1891â1897. Alonso Hagen went fishing 160 times and lost 2,231 trout for a seven-year average of 13.9 trout lost every time he went fishing.

Under the grand totals, there was a little Trout Fishing in America epitaph by Alonso Hagen. It said something like:

Â

“I've had it.

I've gone fishing now for seven years

and I haven't caught a single trout.

I've lost every trout I ever hooked.

They either jump off

or twist off.

or squirm off

or break my leader

or flop off

or fuck off.

I have never even gotten my hands on a trout.

For all its frustration,

I believe it was an interesting experiment

in total loss

but next year somebody else

will have to go trout fishing.

Somebody else will have to go

out there.”

Â

We came down the road from Lake Josephus and down the road from Seafoam. We stopped along the way to get a drink of water. There was a small monument in the forest. I walked over to the monument to see what was happening. The glass door of the lookout was partly open and a towel was hanging on the other side.

At the center of the monument was a photograph. It was the classic forest lookout photograph I have seen before, from that America that existed during the 1920s and 30s.

There was a man in the photograph who looked a lot like Charles A. Lindbergh. He had that same

Spirit of St. Louis

nobility and purpose of expression, except that his North Atlantic was the forests of Idaho.

There was a woman cuddled up close to him. She was one of those great cuddly women of the past, wearing those pants they used to wear and those hightop, laced boots.

They were standing on the porch of the lookout. The sky was behind them, no more than a few feet away. People in those days liked to take that photograph and they liked to be in it.

There were words on the monument. They said:

Â

“In memory of Charley J. Langer, District Forest Ranger, Challis National Forest, Pilot Captain Bill Kelly and Co-Pilot Arthur A. Crofts, of the U.S. Army killed in an Airplane Crash April 5, 1943, near this point while searching for survivors of an Army Bomber Crew.”

Â

O it's far away now in the mountains that a photograph guards the memory of a man. The photograph is all alone out there. The snow is falling eighteen years after his death. It covers up the door. It covers up the towel.

Often I return to the cover of

Trout Fishing in America.

I took the baby and went down there this morning. They were watering the cover with big revolving sprinklers. I saw some bread lying on the grass. It had been put there to feed the pigeons!

The old Italians are always doing things like that. The bread had been turned to paste by the water and was squashed flat against the grass. Those dopey pigeons were waiting until the water and grass had chewed up the bread for them, so they wouldn't have to do it themselves.

I let the baby play in the sandbox and I sat down on a bench and looked around. There was a beatnik sitting at the other end of the bench. He had his sleeping bag beside him and he was eating apple turnovers. He had a huge sack of apple turnovers and he was gobbling them down like a turkey. It was probably a more valid protest than picketing missile bases.

The baby played in the sandbox. She had on a red dress and the Catholic church was towering up behind her red dress. There was a brick John between her dress and the church. It was there by no accident. Ladies to the left and gents to the right.

A red dress, I thought. Wasn't the woman who set John Dillinger up for the FBI wearing a red dress? They called her “The Woman in Red.”

It seemed to me that was right. It was a red dress, but so far, John Dillinger was nowhere in sight. My daughter played alone in the sandbox.

Sandbox minus John Dillinger equals what?

The beatnik went and got a drink of water from the fountain that was crucified on the wall of the brick John, more toward the gents than the ladies. He had to wash all those apple turnovers down his throat.

There were three sprinklers going in the park. There was one in front of the Benjamin Franklin statue and one to the side of him and one just behind him. They were all turning in circles. I saw Benjamin Franklin standing there patiently through the water.

The sprinkler to the side of Benjamin Franklin hit the left-hand tree. It sprayed hard against the trunk and knocked some leaves down from the tree, and then it hit the center tree, sprayed hard against the trunk and more leaves fell. Then it sprayed against Benjamin Franklin, the water shot out to the sides of the stone and a mist drifted down off the water. Benjamin Franklin got his feet wet.

The sun was shining down hard on me. The sun was bright and hot. After a while the sun made me think of my own discomfort. The only shade fell on the beatnik.

The shade came down off the Lillie Hitchcock Coit statue of some metal fireman saving a metal broad from a mental fire. The beatnik now lay on the bench and the shade was two feet longer than he was.

A friend of mine has written a poem about that statue. Goddamn, I wish he would write another poem about that statue, so it would give me some shade two feet longer than my body.

I was right about “The Woman in Red,” because ten minutes later they blasted John Dillinger down in the sandbox. The sound of the machine-gun fire startled the pigeons and they hurried on into the church.

My daughter was seen leaving in a huge black car shortly after that. She couldn't talk yet, but that didn't make any difference. The red dress did it all.

John Dillinger's body lay half in and half out of the sandbox, more toward the ladies than the gents. He was leaking blood like those capsules we used to use with oleomargarine, in those good old days when oleo was white like lard.

The huge black car pulled out and went up the street, bat-light shining off the top. It stopped in front of the ice-cream parlor at Filbert and Stockton

An agent got out and went in and bought two hundred double-decker ice-cream cones. He needed a wheelbarrow to get them back to the car.

The last time we met was in July on the Big Wood River, ten miles away from Ketchum. It was just after Hemingway had killed himself there, but I didn't know about his death at the time. I didn't know about it until I got back to San Francisco weeks after the thing had happened and picked up a copy of

Life

magazine. There was a photograph of Hemingway on the cover.

“I wonder what Hemingway's up to,” I said to myself. I looked inside the magazine and turned the pages to his death. Trout Fishing in America forgot to tell me about it. I'm certain he knew. It must have slipped his mind.

The woman who travels with me had menstrual cramps. She wanted to rest for a while, so I took the baby and my spinning rod and went down to the Big Wood River. That's where I met Trout Fishing in America.

I was casting a Super-Duper out into the river and letting it swing down with the current and then ride on the water up close to the shore. It fluttered there slowly and Trout Fishing in America watched the baby while we talked.

I remember that he gave her some colored rocks to play with. She liked him and climbed up onto his lap and she started putting the rocks in his shirt pocket.

We talked about Great Falls, Montana. I told Trout Fishing in America about a winter I spent as a child in Great Falls. “It was during the war and I saw a Deanna Durbin movie seven times,” I said.

The baby put a blue rock in Trout Fishing in America's shirt pocket and he said, “I've been to Great Falls many times. I remember Indians and fur traders. I remember Lewis and Clark, but I don't remember ever seeing a Deanna Durbin movie in Great Falls.”

“I know what you mean,” I said. “The other people in Great Falls did not share my enthusiasm for Deanna Durbin. The theater was always empty. There was a darkness to that theater different from any theater I've been in since. Maybe it was the snow outside and Deanna Durbin inside. I don't know what it was.”

“What was the name of the movie?” Trout Fishing in America said.

“I don't know,” I said. “She sang a lot. Maybe she was a chorus girl who wanted to go to college or she was a rich girl or they needed money for something or she did something. Whatever it was about, she sang! and sang! but I can't remember a God-damn word of it.

“One afternoon after I had seen the Deanna Durbin movie again, I went down to the Missouri River. Part of the Missouri was frozen over. There was a railroad bridge there. I was very relieved to see that the Missouri River had not changed and begun to look like Deanna Durbin.

“I'd had a childhood fancy that I would walk down to the Missouri River and it would look just like a Deanna Durbin movieâa chorus girl who wanted to go to college or she was a rich girl or they needed money for something or she did something.