Trout Fishing in America (14 page)

Read Trout Fishing in America Online

Authors: Richard Brautigan

It looked like a fine stream. I put my hand in the water. It was cold and felt good.

I decided to go around to the side and look at the animals. I saw where the trucks were parked beside the railroad tracks. I followed the road down past the piles of lumber, back to the shed where the animals were.

The salesman had been right. They were practically out of animals. About the only thing they had left in any abundance were mice. There were hundreds of mice.

Beside the shed was a huge wire birdcage, maybe fifty feet high, filled with many kinds of birds. The top of the cage had a piece of canvas over it, so the birds wouldn't get wet when it rained. There were woodpeckers and wild claries and sparrows.

On my way back to where the trout stream was piled, I found the insects. They were inside a prefabricated steel building that was selling for eighty-cents a square foot. There was a sign over the door. It said

Â

INSECTS

Â

On this funky winter day in rainy San Francisco I've had a vision of Leonardo da Vinci. My woman's out slaving away, no day off, working on Sunday. She left here at eight o'clock this morning for Powell and California. I've been sitting here ever since like a toad on a log dreaming about Leonardo da Vinci.

I dreamt he was on the South Bend Tackle Company payroll, but of course, he was wearing different clothes and speaking with a different accent and possessor of a different childhood, perhaps an American childhood spent in a town like Lordsburg, New Mexico, or Winchester, Virginia.

I saw him inventing a new spinning lure for trout fishing in America. I saw him first of all working with his imagination, then with metal and color and hooks, trying a little of this and a little of that, and then adding motion and then taking it away and then coming back again with a different motion, and in the end the lure was invented.

He called his bosses in. They looked at the lure and all fainted. Alone, standing over their bodies, he held the lure in his hand and gave it a name. He called it “The Last Supper.” Then he went about waking up his bosses.

In a matter of months that trout fishing lure was the sensation of the twentieth century, far outstripping such shallow accomplishments as Hiroshima or Mahatma Gandhi. Millions of “The Last Supper” were sold in America. The Vatican ordered ten thousand and they didn't even have any trout there.

Testimonials poured in. Thirty-four ex-presidents of the United States all said, “I caught my limit on âThe Last Supper.'”

He went up to Chemault, that's in Eastern Oregon, to cut Christmas trees. He was working for a very small enterprise. He cut the trees, did the cooking and slept on the kitchen floor. It was cold and there was snow on the ground. The floor was hard. Somewhere along the line, he found an old Air Force flight jacket. That was a big help in the cold.

The only woman he could find up there was a three-hundred-pound Indian squaw. She had twin fifteen-year-old daughters and he wanted to get into them. But the squaw worked it so he only got into her. She was clever that way.

The people he was working for wouldn't pay him up there. They said he'd get it all in one sum when they got back to San Francisco. He'd taken the job because he was broke, really broke.

He waited and cut trees in the snow, laid the squaw, cooked bad foodâthey were on a tight budgetâand he washed the dishes. Afterwards, he slept on the kitchen floor in his Air Force flight jacket.

When they finally got back to town with the trees, those guys didn't have any money to pay him off. He had to wait around the lot in Oakland until they sold enough trees to pay him off.

“Here's a lovely tree, ma'am.”

“How much?”

“Ten dollars.”

“That's too much.”

“I have a lovely two-dollar tree here, ma'am. Actually, it's only half a tree, but you can stand it up right next to a wall and it'll look great, ma'am.”

“I'll take it. I can put it right next to my weather clock. This tree is the same color as the queen's dress. I'll take it.

You said two dollars?”

“That's right, ma'am.”

“Hello, sir. Yes . . . Uh-huh . . . Yes . . . You say that you want to bury your aunt with a Christmas tree in her coffin? Uh-huh . . . She wanted it that way . . . I'll see what I can do for you, sir. Oh, you have the measurements of the coffin with you? Very good . . . We have our coffin-sized Christmas trees right over here, sir.”

Finally he was paid off and he came over to San Francisco and had a good meal, a steak dinner at Le Boeuf and some good booze, Jack Daniels, and then went out to the Fillmore and picked up a good-looking, young, Negro whore, and he got laid in the Albert Bacon Fall Hotel.

The next day he went down to a fancy stationery store on Market Street and bought himself a thirty-dollar fountain pen, one with a gold nib.

He showed it to me and said, “Write with this, but don't write hard because this pen has got a gold nib, and a gold nib is very impressionable. After a while it takes on the personality of the writer. Nobody else can write with it. This pen becomes just like a person's shadow. It's the only pen to have. But be careful.”

I thought to myself what a lovely nib trout fishing in America would make with a stroke of cool green trees along the river's shore, wild flowers and dark fins pressed against the paper.

“The Eskimos live among ice all their lives but have no single word for ice.”â

Man: His First Million Years

, by M. F. Ashley Montagu

Â

“Human language is in some ways similar to, but in other ways vastly different from, other kinds of animal communication. We simply have no idea about its evolutionary history, though many people have speculated about its possible origins. There is, for instance, the âbow-bow' theory, that language started from attempts to imitate animal sounds. Or the âding-dong' theory, that it arose from natural sound-producing responses. Or the âpooh-pooh' theory, that it began with violent outcries and exclamations . . . We have no way of knowing whether the kinds of men represented by the earliest fossils could talk or not . . . Language does not leave fossils, at least not until it has become written . . .” â

Man in Nature

, by Marston Bates

Â

“But no animal up a tree can initiate a culture.”â“The Simian Basis of Human Mechanics,” in

Twilight of Man

, by Earnest Albert Hooton

Â

Expressing a human need, I always wanted to write a book that ended with the word Mayonnaise.

Â

Feb 3â1952

Dearest Florence and Harv.

I just heard from Edith about

the passing of Mr. Good. Our heart

goes out to you in deepest sympathy

Gods will be done. He has lived a

good long life and he has gone to

a better place. You were expecting

it and it was nice you could see

him yesterday even if he did not

know you. You have our prayers

and love and we will see you soon.

God bless you both.

Love Mother and Nancy.

P.S.

Sorry I forgot to give you the mayonaise.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

VERSUS

THE SPRINGHILL MINE DISASTER

Â

Â

Â

Â

Writing 20

Â

Â

Â

Â

This book is for Miss Marcia Pacaud of Montreal, Canada.

Â

Â

I like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky.

Â

I like to think

(right now, please!)

of a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computers

as if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

Â

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal

brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

Â

Â

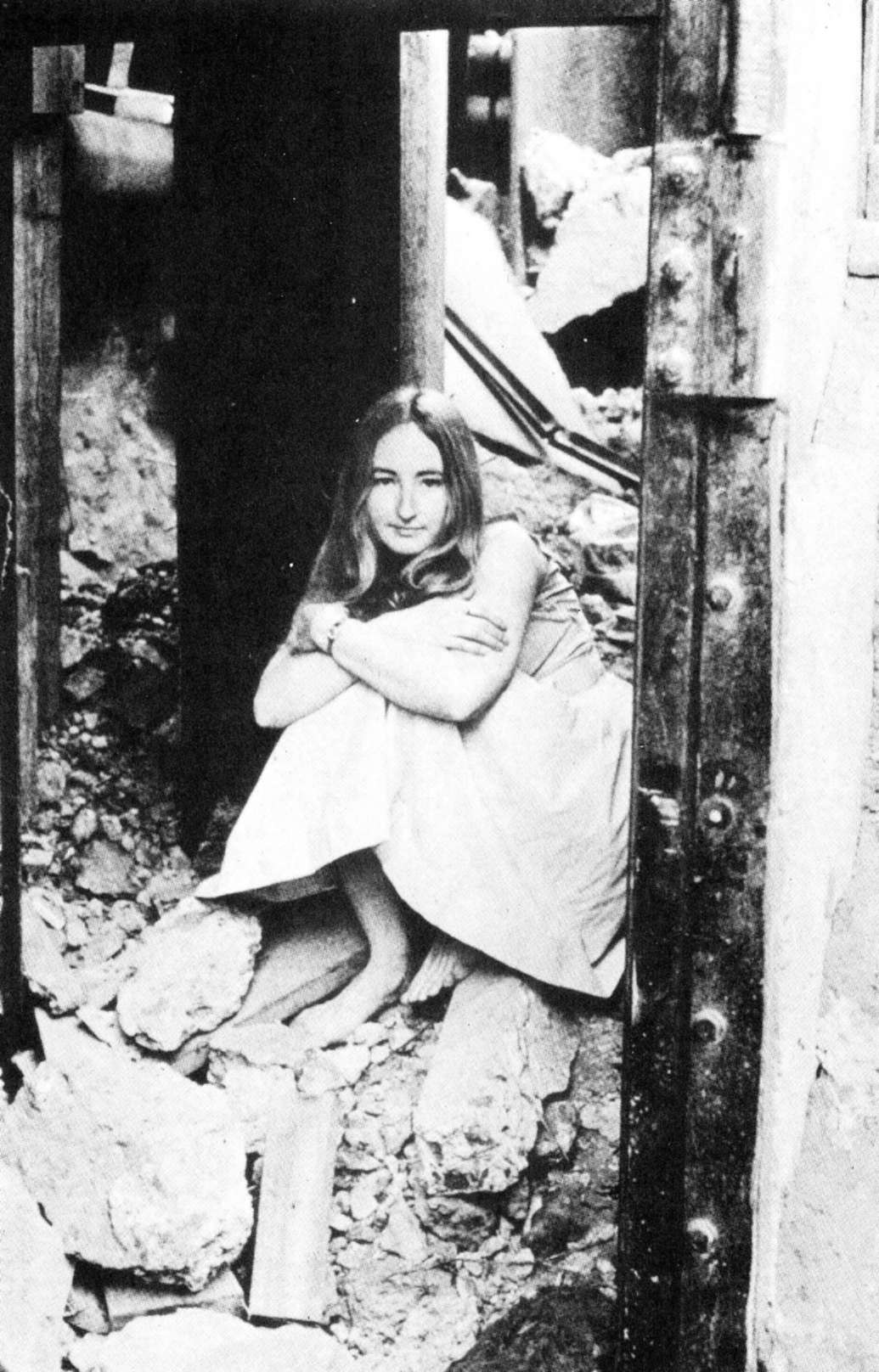

Horse child breakfast,

what are you doing to me?

with your long blonde legs?

with your long blonde face?

with your long blonde hair?

with your perfect blonde ass?

Â

I swear I'll never be the

same again!

Â

Horse child breakfast,

what you're doing to me,

I want done forever.

Â

For the soldiers of the Seventh Cavalry who were killed at the Little Bighorn River and the passengers who were lost on the maiden voyage of the Titanic.

God bless their souls.

Â

Yes! it's true all my visions

have come home to roost at last.

They are all true now and stand

around me like a bouquet of

lost ships and doomed generals.

I gently put them away in a

beautiful and disappearing vase.

Â

Â

I go to bed in Los Angeles thinking

about you.

Â

Pissing a few moments ago

I looked down at my penis

affectionately.

Â

Knowing it has been inside

you twice today makes me

feel beautiful.

Â

3

A.M

January 15, 1967

Â

Â

Three crates of Private Eye Lettuce,

the name and drawing of a detective

with magnifying glass on the sides

of the crates of lettuce,

form a great cross in man's imagination

and his desire to name

the objects of this world.

I think I'll call this place Golgotha

and have some salad for dinner.

Â

Â

O beautiful

was the werewolf

in his evil forest.

We took him

to the carnival

and he started

crying

when he saw

the Ferris wheel.

Electric

green and red tears

flowed down

his furry cheeks.

He looked

like a boat

out on the dark

water.

Â

Â

For Marcia

Because you always have a clock

strapped to your body, it's natural

that I should think of you as the

correct time:

with your long blonde hair at 8:03,

and your pulse-lightning breasts at

11:17, and your rose-meow smile at 5:30,

I know I'm right.

Â

- Get enough food to eat,

and eat it. - Find a place to sleep where it is quiet,

and sleep there. - Reduce intellectual and emotional noise

until you arrive at the silence of yourself,

and listen to it. - Â

Â

Oh, how perfect death

computes an orange wind

that glows from your footsteps,

Â

and you stop to die in

an orchard where the harvest

fills the stars.

Â

This poem was found written on a paper bag by Richard Brautigan in a laundromat in San Francisco. The author is unknown.

Â

By accident, you put

Your money in my

Machine (#4)

By accident, I put

My money in another

Machine (#6)

On purpose, I put

Your clothes in the

Empty machine full

Of water and no

Clothes

Â

It was lonely.

Â

Â

Ah,

you're just a copy

of all the candy bars

I've ever eaten.

Â

Â

The petals of the vagina unfold

like Christopher Columbus

taking off his shoes.

Â

Is there anything more beautiful

than the bow of a ship

touching a new world?

Â