Tudor Queenship: The Reigns of Mary and Elizabeth (21 page)

Read Tudor Queenship: The Reigns of Mary and Elizabeth Online

Authors: Alice Hunt,Anna Whitelock

Tags: #Royalty, #Tudors, #England/Great Britain, #Nonfiction, #Biography & Autobiography

Antichristian then, miserable & damnable, is the doctrine of all such as dare say, that Popes may either set up, or pull down Princes, discharge the subject of his obedience, put a knife in the hand of any to sheath it in the bowels of their soveraignes.

Addressing papists directly, Leigh thundered that no “boysterous bull” could remove Elizabeth nor “the croaking of your frogges, and Locusts, your Jesuited crew and Seminarie broode, can blast our doctrine, blemish our state, or bereave us of our Soveraigne, disquiet you may, destroy you may not.”

41

Although a digression from the central theme of these sermons, the argument these preachers presented against tyrannicide was nonetheless integral to their message.

IV

For a different group of Protestants, those we label conformists, the association of Elizabeth with David or Solomon proved valuable in defense of the royal supremacy and the Elizabethan Church after these two came under heavy attack from Presbyterians and sectarians during the last fifteen years of the reign. The role of the priests, the authority of the monarch over his priests, and the importance of singing in prayers of thanksgiving at the time of David, all became part of conformist Protestants’ justification for the style of divine worship and the organization of the Church then in place in England.

42

Thomas Morton was one of these. In the first part of his 1597 treatise,

Salomon

, Morton challenged Catholic claims to the right of resistance on the grounds that God had given David and Solomon the supreme authority and absolute power within Israel and that consequently no such power or right remained in the hands of their subjects. Morton then moved on to defend Elizabeth’s absolute power over the Church by showing that David, Solomon, and their successors had by their own authority made the laws and orders concerning religion and the Temple. Citing the examples of Abimelech (put to death by David) and Abiathor (deposed and condemned by Solomon), Morton further demonstrated that priests were no less subject to royal authority than was the laity. The contemporary relevance of this biblical exegesis was stated clearly in the preface to the book and was evident from its frontispiece. In the preface to the reader, Morton explained that his description of the supreme authority of Old Testament kings over their Church provided “a most true and lively picture of her Majestie’s state and crowne.”

43

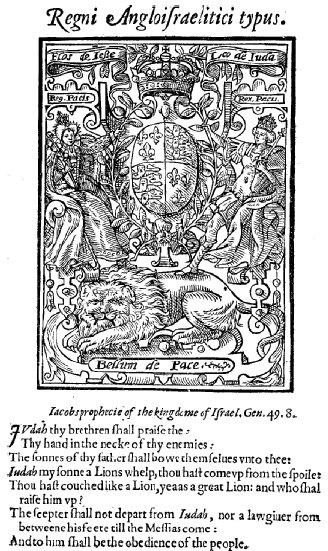

The frontispiece presented Elizabeth as virtually a mirror image of the biblical king. Both monarchs wear the same royal insignia, hold up the English royal coat of arms, and rest their foot on a lion that doubles up as a symbol of the royal houses of David and Tudor.

Figure 6.1 Elizabeth as David. Frontispiece to Thomas Morton's Salomon or "A treatise declaring the state of the kingdome of Israel, as it was in the daies of Salomon (London, 1596)

That both stand for divinely ordained monarchy and a form of theocratic kingship is made clear by the biblical verse beneath the illustration (see Figure 6.1). Adapted from Genesis 49.8 it ends with the following words: “The sceptre shall not depart from Judah nor a lawgiver from between his feet till the Messia’s come. And to him shall be the obedience of the people.”

44

V

In an apparently throwaway comment in his preface Thomas Morton drew attention to the problem of the succession. Through the telling of an anecdote about a Glastonbury monk troubled about the succession, Morton recommended that Elizabeth’s subjects should be silent on the issue: “Take thou no thought for such matters, for the kingdome of England is God’s kingdome.”

45

My guess is that Morton brought in this somewhat incongruous remark in order to prevent his readers from making a “false” analogy. It would be all too easy for them to look at their own time as a mirror image of Israel during the last years of David’s reign in the matter of succession; after all they would not be the first to do so. Peter Wentworth had laid before Elizabeth the example of David and Solomon when exhorting her to settle the succession in his

Pithie Exhortation.

Like David, explained Wentworth, Elizabeth had many potential successors to her throne and “the contention for the crowne” was likely to be great on her death: “Wherefore as the state of Israell then mooved David to make his successor knowne: so nowe the state of England ought to move you.”

46

Elizabeth, he argued, could only gain strength from naming her heir, for once David had appointed Solomon, his son Adonijah was “so dasht and crusht” that his resort to arms faded away. The same outcome would surely occur once Elizabeth had established the succession.

47

Few were as brave or foolhardy as Wentworth, who died in the Tower, and the succession issue was afterward either debated in unprinted manuscripts or discussed in coded language within a more public arena. The David and Solomon analogy was part of this succession discourse, not least because Robert Persons, aka Doleman, had used the biblical example to justify elected monarchy in his

Conference about the Next Succession

. Solomon could hardly be called David’s natural successor, as he was the tenth son of David, but his election had nonetheless been in accordance with God’s will. The exclusion of Adonijah and accession of Solomon, argued Doleman, therefore, demonstrated the general principle that the election and exclusion of princes “when their designements are to good endes and for just respects and causes, are allowed also by God, and oftentymes, are his owne special driftes and dispositions, though they seme to come from man.”

48

One coded reference to the contemporary succession issue can be found in the unpublished “Maxims of State” found amongst Sir Walter Ralegh’s papers but now excluded from his canon. The anonymous author, who presented his observations about good policy and government through classical, biblical, and historical examples, commented on David’s difficulties in ruling when “grown into age” and commended his behavior after the suppression of Absalom’s revolt. David, wrote the author, “assembled a Parliament of his whole Realm, and took occasion upon the designing of his successor to commend upon them the succession of his house, and the continuance and maintenance of God’s true worship then established.” By this action and in naming Solomon as his heir, David “retained his Majestie and Authority in his old age.”

49

Although nowhere spelled out, the observation had an obvious relevance to Elizabeth’s queenship in the wake of the Essex revolt. And it is difficult to see what other relevance it might have within the context of Elizabethan (or even early Stuart) politics, when the maxims were written.

A second coded reference to the succession issue can be found in George Peele’s play

David and Bethsabe with the Tragedie of Absalon

, performed by the Lord Admiral’s Company.

50

The climax of the drama is the rebellion and death of Absalom, events presented as the just dessert for a rebel and usurper who betrayed his closest kin and sovereign lord (another obvious swipe at Mary Stuart). The scene that follows Absalom’s death, however, introduces Solomon for the first time in the play and deals with the succession. David expresses his understanding that Solomon will be the one who “shall surely sit upon my throne” in spite of the king’s reservations about his son’s suitability (l. 1682). But this informal recognition is not enough for the prophet Nathan who wants David to “make him promise, that he may succeed/And rest old Israels bones from broiles of war” (ll. 1774–5). This David does. The action then moves swiftly onto David’s inconsolable grief on learning of the death of Absalom, a reaction that is deemed offensive to God and nearly costs the king the support of his generals. There seems to be no dramatic justification for the inclusion of the issue of the succession in the play at this point. Furthermore, in terms of chronology, the scene deviates from the scriptures, the source that Peele followed closely in all other respects. The only reason for the succession scene to be played out is its contemporary relevance in 1594 when the play was entered into the Stationers’ Register, and in 1599 when the first quarto edition was printed. Again the message underscores the need for Elizabeth to name her successor.

VI

Although Elizabeth was associated with David and/or Solomon by her subjects, it is evident that she did relatively little to fashion herself as one or the other of the biblical kings. In her speeches, she did not refer to herself as David or Solomon. Unlike Henry VIII, she is not known to have commissioned any painting or print that identified her with the biblical kings, even when she used visual emblems to display her Protestantism; nor did she possess anything comparable to Henry’s personal psalter where the miniatures portray the king as David playing a harp and killing Goliath and the marginal annotations draw parallels between Henry’s situation and his biblical predecessor.

51

It could be argued that Elizabeth assumed the identity of David and Solomon when quotations from the former’s psalms and latter’s prayers were incorporated in some of the prayers and devotional poems written in the authorial voice of the queen.

52

However, it is difficult to know how many of these were actually Elizabeth’s own work. Furthermore, as Margaret Hannay reminds us, paraphrasing psalms was a well-established genre among English Protestants, and women especially “prayed in the words of the Psalmist.”

53

But even if Elizabeth’s appropriation of their writings was intended as an act of public self-identification with David and Solomon, it did not last long; few examples can be found after 1579 when, as we have seen, resemblances between her and the Old Testament kings actually became more pronounced in book dedications and sermons. Elizabeth, then, seems to have left the biblical tropes to her critics, while she preferred to cooperate in promoting the image of the “Virgin Queen.” We appear to have here another dimension to the “competition for representation” originally detected by Susan Frye.

54

During Elizabeth’s own lifetime her critics had the wider audience: the sermons, for example, were preached at court, Paul’s Cross, and the universities, besides going into print (sometimes in more than one edition). But in the long run Elizabeth won the competition hands down, for it was her preferred image of the Virgin Queen that became best known to posterity.

Notes

* I am grateful to Paulina Kewes for pointing me towards some references, to Kathryn Murphy for alerting me to her work, and to Alec Ryrie.

- John King, “The Godly Woman in Elizabethan Iconography,”

RQ

38 (1985): 41–84 and

Tudor Royal Iconography

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 105–6, 153–4, 234–5. See also Alexandra Walsham, “‘A Very Deborah?’ The Myth of Elizabeth I as a Providential Monarch,” in

The Myth of Elizabeth

, ed. Susan Doran and Thomas S. Freeman (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 143–68. - King makes brief references, as does Margret Christian, “Elizabeth’s Preachers and the Government of Women,”

SCJ

24 (1993): 561–76. Two recent essays look at male representation but in a limited number of texts and from a gendered perspective: Michelle Osherow, “‘A Poore Shepherde and his Slinge:’ A Biblical Model for a Renaissance Queen,” in

Elizabeth I: Always Her Own Free Woman

, ed. Carole Levin, Jo Eldridge Carney, and Debra Barrett-Graves (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2003), 119–30; and Linda S. Shenk, “Queen Solomon,” in

Queens and Power in Medieval and Early Modern England

, ed. Carole Levin and Robert Bucholz (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 98–125. - Donald Stump claimed that after 1582 “writers connected to the court were no longer making extensive use of Old Testament figures as images or examples for Elizabeth”: “Abandoning the Old Testament: Shifting Paradigms for Elizabeth 1578–82,”

Explorations in Renaissance Culture

30 (2004): 89–109, especially 89–90. - John Davies,

Microcosmos...

(1603), 152. - John Williams,

Greate Britains Salomon: A sermon preached at the magnificent funeral of...King, James...

(1625). - Lodowick Lloyd,

The pilgrimage of princes...

(1573), 161. - David provides Anthony Munday’s example for lechery in

The mirror of mutability

(1579), C–Civ. For Solomon, see

A godly ballad declaring by the Scriptures the plagues that haue insued whordome

(1566) and Lloyd,

Pilgrimage of princes

, 161. - Other early examples include John Aylmer,

An harborovve for faithfull and trevve subiectes...

(London, 1559) and Thomas Brice,

A compendiou[s regi]ster in metre...

(London, 1559). - Anon,

The Boke of Psalmes...with brief and apt annotations in the margent…

(Geneva, 1559), *iiiv–*v. - BL Harleian MS 149, fol. 148.

- Sapientia Solomonis...

, ed. Elizabeth Rogers Payne (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1938), especially 53, 129. - Proceedings in the Parliaments of Elizabeth I

, ed. T. E. Hartley, 3 vols. (Leicester: University of Leicester Press, 1981), II: 252. - Hartley (ed.),

Proceedings

, I: 274–89. - Published in 1585, the sermon is usually considered a response to either the Throckmorton or Babington Plot, but Kathryn Murphy has convincingly argued that it was written just after the Ridolfi Plot: “The Date of Edwin Sandys’ Paul’s Cross Sermon,”

Notes and Queries

53 (2006): 430–2. - Edwin Sandys,

Sermons

(1585), 362–4, 368. - Edward Dering,

A sermo[n] preached before the Quenes Maiestie

...(1570), Eii. - John Foxe,

Acts and Monumentes

(1576),

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs Variorum Edition Online,

2007. - Edmund Bunny,

The coronation of David...

(1588), C1, 72. - Thomas Rogers,

A Golden Chaine taken out of the rich Treasurehouse of the Psalmes of King David and the pretious Pearles of King Salomon...

(London, 1579), A5v. - Rogers,

Golden Chaine,

Ai–5. - The

Selected Works of Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke

, ed. Margaret P. Hannay, Noel J. Kinnamon and Michael G. Brennan (Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2005), 159–63 (ll. 54, 66, 70, 74, 104, 80). - Margaret P. Hannay, “‘Princes You as Men Must Dy’: Genevan Advice to Monarchs in the

Psalms

of Mary Sidney,”

ELR

19 (1989): 22–41. - John Rainolds,

A sermon upon part of the 18

th

Psalm...

(Oxford, 1586), B3. - Rainolds,

A sermon,

B2v, B3v–4. - William Leigh,

Queene Elizabeth, paraleld in her princely virtues...

(1612), 28. - Leigh,

Elizabeth, paraleld

, 31, 35–6. - Isaac Colfe,

A sermon preached on the queenes day...1587...

(1588), B4–B5. - Colfe,

A sermon

, B4v–5v; Rainolds,

A sermon,

B5; Leigh,

Elizabeth, paraleld,

46–9, 54–6; John Prime, the

consolations of David, briefly applied to Queen Elizabeth...

(Oxford, 1588), B4. - Rainolds,

A sermon

, B5. - Hartley (ed.),

Proceedings,

II: 217. See also Peter E. MacCulloch, “Out of Egypt: Richard Fletcher’s Sermon before Elizabeth I after the Execution of Mary Queen of Scots” in

Dissing Elizabeth

, ed. Julia M. Walker (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998), 134. - Thomas White,

A sermon preached at Paules Crosse the 17. of Nouember An. 1589...

fols. 51ff. - Leigh,

Elizabeth, paraleld

, 51. - Sir Francis Hastings,

An apologie or defence of the watch-word...

(1600), 137. - Prime,

Consolations of David,

B4. - John Prime,

A sermon briefly comparing the estate of King Salomon and his subiectes togither with the condition of Queene Elizabeth and her people

(1585), B-B1, A2v–3, A5v–6. - John Bridges,

The supremacie of Christian princes...

(1573), 930. - Thomas Bilson,

The true difference betweene Christian subiection and unchristian rebellion

(1585), 321, 323. - Francis Bacon,

A letter written out of England...

(1599), 10. - Prime,

Sermon briefly comparing the estate of King Salomon,

A2. - Rainolds,

A sermon

, B4. - Leigh,

Elizabeth, paraleld,

8, 10. - John Bridges,

A defence of the gouernment established in the Church of

Englande...

(1587). For example, David liked singing as part of the praise of God (600) and the wearing of vestments (610). See also John Whitgift,

A godlie service preached at Paul’s Cross 1589

(1590), C3, C5 and Thomas Bell,

Thomas Bels motiues concerning Romish faith and religion

(1593). - Thomas Morton,

Salomon

(London, 1596), A4v and 36, 39–40, 46. - The last line is a complete fabrication. In the Geneva Bible, the verse finishes “and the people shal be gathered unto him.”

- Morton,

Salomon

, A4v. - Peter Wentworth,

A Pithie Exhortation

(Edinburgh, 1598), 14–15. - Wentworth,

Pithie Exhortation,

52–3. - R. Doleman,

A conference about the next succession...

(Antwerp, 1594), 128. See also 35, 104. - Maxims of State...

(London, 1656), 77–8 (under “Politicall Prince”). - George Peele, the

love of King David and fair Bethsabe

, ed. W. W. Greg, Malone Society (London, 1912). - James P. Carley,

King Henry’s Prayer Book: Commentary

(London: Folio Society, 2009). - Precationes privatae

(1563) and the

Christian Prayers and Meditations in English,

French, Italian, Spanish, Greeke, and Latine

(1569). Shenk,

Queen Solomon

, claims Elizabeth did fashion herself as Solomon, but some prayers she cites are not Elizabeth’s unadulterated compositions. - Margaret Hannay, “‘So may I with the

Psalmist

truly say’: Early Modern Englishwomen’s Psalm Discourse,” in

Write or Be Written

, ed. Barbara Smith and Ursula Appelt (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), 107, 111. - Susan Frye,

Elizabeth I: The

Competition

for Representation

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).