Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials (21 page)

Read Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials Online

Authors: Erich Von Daniken

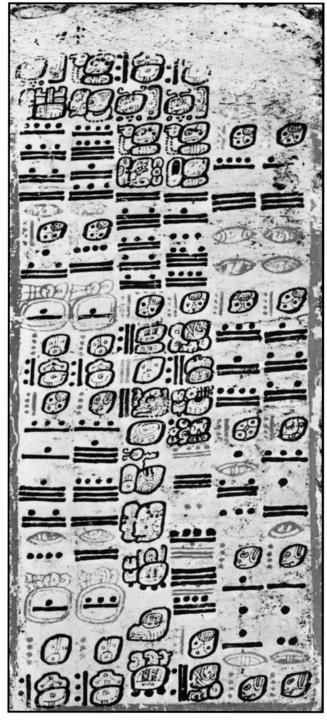

Folios from the Madrid Codex. Author's own images.

Bishop Diego de Landa had written in his apologia: "The most important thing the tribal chiefs carried around with their territories were their scientific books."5

His countryman, Jose de Acosta, went further: "In the Yucatan there were bound and folded books in which the Indios stored their knowledge of the planets, nature and their ancient lore."'

Only four Maya manuscripts from pre-Spanish times survived the destruction in Central America. They are known as codices, and they can be found today in Mexico City, Madrid, Paris, and Dresden. The Madrid Codex was found by Abbe Brasseur, the same man who found the text by Diego de Landa, in the possession of a professor from Madrid's school for diplomats. The Paris Codex was discovered in a waste paper basket of the Parisian National Library, and the Dresden Codex was brought to Dresden from Italy by Johann Christian Gotze, a librarian from the Royal Library. That was back in 1739. Gotze wrote at the time:

Our Royal Library now has the advantage over many others, for it possesses a rare treasure. It was discovered in private hands in Vienna, and had been kept more by chance as its owner did not suspect its worth. Without doubt, it is from the estate of some Spaniard who was either in America himself or one of his ancestors was.'

Did not suspect its worth? Phew! These days the Dresden Codex is worth several million dollars.

The fourth of the Maya manuscripts is called the Grolier Codex. It consists of 11 incomplete pages that discuss the planet Venus.

All of the Maya texts are written on thin parchments made of bast fiber from the wild fig trees that grew in the area. Originally, the bark of the trees would have been made more elastic by treating it with the sap of the rubber tree. Then it would have been painted with starch from vegetable tubers and laid out to dry before being painted in four colors using soft feathers. Finally the manuscripts were folded in a concertina-like fashion.

The age of the Mayan manuscripts is unknown. If they are copies of older documents (as is likely) their content could be at least 2,000 years old (if not more!). The Paris Codex contains prophecies, the Madrid Codex is a horoscope, apparently, and the Dresden Codex is filled with mathematical and astronomical relationships. All are now readable, thanks to Bishop Diego de Landa, who provided us with the key to the Mayan numerical system.

'he Dresden Codex

'he Dresden Codex

Maya scholars have been trying to crack the codices for two hundred years. The meticulous academics have been able to reconstruct much-but just as much remains shrouded in the mists of interpretation. Professor Thomas Barthel, an expert in Maya writing systems, talks of an "evident mixed character"' because the same signs can sometimes mean completely different things. There are also blocks of hieroglyphics that are placed in the middle of a number text, or plays on words that "offer numerous different possibilities for interpretation whose senses are often completely at odds with one another."'

Nevertheless, what the academics have found is simply breathtaking. The Dresden Codex talks about Venus orbits, certain gods who are described as the "lords of the heavens," a thunder and lightning god, and of course the complicated Maya calendar. Maya academics have labeled the confusing panoply of gods with different letters. In the Dresden Codex, much is carried out by the gods A, D, E, and N, although it is often unclear which god is responsible for which deed. Six leaves of the Dresden Codex contain astronomical profiles of Venus, two leaves discuss the Martian orbit, and four the Jovian orbit and even its moons. Some of the pages are primarily concerned with the Moon, Mercury, and Saturn, but the constellations Orion, Gemini, and the Pleiades are also mentioned. Filled with complex calculations, the tables even present the reference points of the planets in relation to each other and their respective positions with regard to the Earth. Then come periods of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars years adding up to 135,200 days."' The ancient Maya even dealt with astronomical numbers of 400 million years.

4.4. A page from the Dresden Codex filled with mathematical calculations. Author's own image.

The Maya astronomy documented in the Dresden Codex is not fully understood, even today. Several folios talk of battles between the planets," and there are seven sheets of so-called eclipse tables containing the dates of every single eclipse from the past and the future. In 1938, Professor Herbert Noll Hussum, the best-known Dresden Codex specialist of the age, wrote: "The eclipse tables are so ingeniously drawn up that they contain not only every single possible eclipse visible in the area for hundreds of years, but also even the not directly observable, purely theoretical eclipses are given exactly-to the precise day."12

That observation was made 70 years ago. It still makes some Maya researchers uneasy. How could a culture that still practiced human sacrifice be such masters of astronomy, exhibiting skills that should have been far beyond their ken. Where did they get this knowledge? Where did the inspiration come from that told them that the planets had a predictable relationship to each other? Centuries of observations, a manic compulsion to create the perfect calendar, or even an addiction to mathematics does not explain this puzzle. As the Earth itself has an elliptical orbit around the Sun and, of course, the other planets are not actually standing still, every observation is susceptible to a certain time lag. Venus, for example, only appears in the same constellation once every eight years; Jupiter every 12 years. What's more, the Maya lived in a geographical area in which it was impossible to observe the stars at all for half the year. In the Dresden Codex, however, there are astronomical points of reference that only appear every 6,000 years! The Maya weren't even around for 6,000 years! Mere calculations are not enough to deduce that the orbit of Venus has to be "put back" a day every 6,000 years. Added to all this, the evidence points to the fact that the Maya were in possession of their astronomical knowledge from the very start-almost as if their tables and books of data and orbital calculations had just fallen to them out of the sky. One Maya specialist explained to me that these kinds of observations could be made in just a few decades. The Maya were a Stone Age people-have we forgotten that? They possessed no modern measurement devices, telescopes, or computers. Even the archaeological objection that the Mayan priest-astronomers on their tall pyramids would have been able to observe the starry skies without having to look through haze and clouds doesn't hold much water. The pyramid towers-such as those in Tikal (Guatemala)-were astronomically aligned at the very planning stage. The astronomical knowledge is, therefore, older than the pyramids themselves.

here Does the Knowledge Come From?

here Does the Knowledge Come From?

Sixty years ago, respected astronomer Robert Henseling shocked the scientific community with some of his conclusions about Maya astronomy:

1. It must be considered impossible that the Mayans had instruments and methods at their disposal for the precise measurement of angles and time.

2. There can be no doubt, however, that the Maya astronomers had knowledge of star constellations from thousands of years in the past, which included reliable information on their type and position on certain calendar dates.

3. This is incomprehensible, unless corresponding observations had been made prior to this period-in other words, thousands of years before the beginning of the Christian calendar-by somebody somewhere and reliably handed down for posterity [author's emphasis].

4. Such achievements, however, are dependent on certain factors. For instance, that in that very prior age there had been a development period of extremely long duration. [author's emphasis].13

Since then, the scant number of experts who have worked on the Dresden Codex are hedgy about making any meaningful comments. I believe that the core of the astronomical knowledge of the Maya must be much older than the academics are willing to concede. Even in classical Greece, an empire rich in top-notch mathematicians and brilliant philosophers, it was sacrilege to assert that the Earth moved around the Sun. Anaxagoras (circa 500-428 Bc) was accused of heresy and forced to flee his home town when he claimed that the Sun was nothing more than a glowing rock. Ptolemy of Alexandria (circa 90-168 AD), who had the benefit of the wisdom of hundreds of years of Egyptian and Babylonian astronomy at his disposal, placed the Earth at the center of his planetary system. It wasn't until Nicolaus Copernicus (1476-1543) came on the scene that there was any serious doubt of the matter. He postulated that it was in fact the Sun that was at the center point of our planetary orbits. After him came Giordano Bruno (1548-1600), Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), and Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), until at last the structure of our solar system, as indeed it came to be called, and the elliptical orbits of the planets were finally fully understood. Yet we are expected to believe that the Stone Age people of the Maya tribes discovered all this in just a few centurieswithout any reliable instruments?

ative American Traditions

ative American Traditions

It is hard to grasp: In Central America there existed an ancient, but highly precise, canon of astronomical knowledge, closely connected to the gods who, for their part, (a) came from "the heavens," (b) clearly were an awe-inspiring bunch, and (c) quite often pushed mankind around. This knowledge came from a god they called "Quetzal Serpent," although such a creature no more existed than a fire-breathing, flying dragon in China. The Mayans were by no means stupid. They wouldn't confuse a quetzal bird with a thundering feathered serpent. This contradiction is simply not compatible with their astronomical expertise. On top of this, we shouldn't view the Maya knowledge in isolation; after all, their cousins, the native North Americans, lived close by. And they all knew the extraterrestrial quetzal serpent, even if it sometimes appeared in a slightly different form. The Tootooch Indians from the Pacific Northwest Coast, United States, called the quetzal serpent the "thunderbird." One of their totem poles for this thunderbird serves as the symbol for the "city of heavenly beings."" The same designation is used by the Canadian First Nations people in British Columbia. Here too the quetzal serpent is known as the thunderbird. It all seems so much more logical. The Pawnee tribe in today's Nebraska are convinced that man was created from the stars, and heavenly teachers came down regularly to Earth "to tell the men and women more about the things they needed to know."" We researchers of today treat the Maya wisdom in an isolated fashion, as if there had never been any other tribes or descendants in other regions that had maintained their lore and traditions in just the same way.