Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials (20 page)

Read Twilight of the Gods: The Mayan Calendar and the Return of the Extraterrestrials Online

Authors: Erich Von Daniken

The Aztecs and the Maya lived according to precise calendar cycles. Buildings were erected in harmony with the calendrical rhythm, and feast days organized according to the calendar. (We do just the same today. Christian festivals like Easter, Whitsun, and Christmas are dominant aspects of our year, and for our international sport events, such as the Olympic Games or the FIFA World Cup, huge infrastructures of new buildings are constructed.) As luck would have it, Cortes's arrival coincided with the end of a calendar period-a time when expectations were traditionally high that the quetzal serpent would finally return. The priests had preached of the event for a long time. And now, finally, the event that the legends had all foretold now also matched the date. The devout high priest Moctezuma could have, may have, or even must have recognized Cortes, this bearded white man, as at least an emissary of the "Quetzal Serpent."

So he received his foreign guest with pomp and ceremony, and even offered him his palace to live in. Cortes enjoyed this generous hospitality for three days, and then he demanded that a chapel be built. Willingly, Moctezuma assembled a team of Aztec artisans to build the Christian house of worship.

The Spaniards saw themselves as an occupying army-as indeed they were-and looked on suspiciously as the worked progressed. On one wall they discovered a freshly plastered spot and suspected that a secret door had been hidden behind it. Secretly, they broke through the wall and found themselves standing in a room filled with gold figures, bars of gold and silver, jewel-encrusted adornments, and fine materials woven with feathers. Cortes estimated the value of the find to be around 162,000 gold pesos (around 10 million dollars in today's money).

During a feast to honor the god Teocalli, the Spaniards waited tensely for a prearranged signal. When it finally came, they struck with deadly effect, murdering 700 unarmed Aztec nobles and priests without warning. The Aztecs lost patience with their leader and overthrew Moctezuma. After making his brother king, they stormed the palace where the Spaniards were quartered. Suddenly Tenochtitlan was thrown into bloody chaos. Cortes had his men burn down the temples and houses. While the Spaniards were abroad butchering the Aztecs with their superior weapons, none other than the toppled monarch Moctezuma, of all people, offered his services as an intermediary-the very idea! It was his last: On June 30, 1520, his outraged countrymen stoned him to death.

Cortes finally gave the order to pack up and carry off the treasure. Heavily laden with gold, silver, and precious jewels, the Spaniards planned to sneak out of Tenochtitlan. A watchman discovered the plunderers and gave out an alarm signal. The Aztecs set off hot on the heels of the Spaniards.

he Night of Sorrows

he Night of Sorrows

This was the noche triste, the night of sorrows, for the Spaniards. They fled in panic. The heavy gold and silver weighed them down heavily. They stumbled and fell; some even drowned in the swamp. Aztec warriors killed great numbers of them. Horses and riders rode through a storm of buzzing arrows; they were bombarded with stones from slingshots. Lances tipped with obsidian-a crystalline stone with a tendency to splinter-pierced the bodies of the hated occupiers. In that terrible night, Cortes' company was reduced by half; he himself was sorely wounded, and the large part of the treasure that had roused their avarice had sunk in the waters and quagmires of the lagoon. Noche triste!

Weeks later Cortes returned with well-armed reinforcements. King Cuauhtemoc, Moctezuma's nephew, was then ruler of Tenochtitlan. He made a good job of defending his city, but under a steady bombardment from the Spanish cannons and siege engines he was finally forced to capitulate. Cortes had free rein to tear apart the city to find its hidden treasures. Even under torture, though, Cuauhtemoc refused to reveal the location of the cache. So he was hanged. After all, this was not just gold, silver, and jewels, but also holy relics, manuscripts, and possibly even gifts from the gods. The Aztec treasure remained missing-to this very day.

Proud Tenochtitlan was finally conquered by the Spaniards in 1521. Its temples and pyramid, idols, stelae, and libraries were all buried in rubble and ash. Nowadays, Mexico City stands on the same site.

Decades followed, during which all of Central America remained under the yoke of Spanish rule. In a series of bloody battles across the lowlands, the Spaniards defeated one Maya tribe after the other. The intractable indigenous peoples were brutally tortured or often simply wiped out. They were forced to live under a reign of violence and terror, and soon-to add insult to injury-they also found themselves being struck down by epidemics. Before too long the Spaniards hardly had to lift a finger to conquer regions, or raze cities to the ground. As the old gods were forced to make way for the new religion under the sign of the cross, the Aztecs and Maya scattered in all directions of the compass. The once-grandiose palaces slowly crumbled. The greedy jungle of the hot and humid rainforest gradually swallowed up the pyramids, penetrated the temples, and pulled down the platforms. Snakes, jaguars, and other kinds of tropical fauna made the sites their homes. Documents of inestimable value merely rotted away, becoming food for the ants and beetles. And the sun finally set on a unique culture with untold knowledge about those gods of the past.

he Sign of the Cross

he Sign of the Cross

Ever more Spanish ships arrived in Central America: Hordes of adventurers, officials, treasure hunters and priests made the trip over the ocean. It was all about gold and christianization. Thirty years after the destruction of Tenochtitlan, a certain young Spaniard arrived in the New World. His name was Fray Diego de Landa. He was born in 1524 to noble parents in Cifuentes in the province of Guadalajara in Spain. This was the time of the church's great expansion, and it was accepted practice for all rich families to send one son or daughter into the church. Diego de Landa started his life in the Franciscan monastery in San Juan de los Reyes at the tender age of 16. Totally devoted to Christ, he prepared for his mission with a program of asceticism. Diego was just 25 years old when he was assigned to a group of young monks whose task it was to convert 300,000 natives on the Yucatan peninsula. Intelligent and infused with the urge to serve Christ to the best of his ability, the young Diego learned the Mayan language in just a few months so that he was already able to deliver his sermons and holy dogma in Mayan by the time he arrived in the Yucatan.

No wonder, then, that Diego was seen as a high flier. In no time at all he was made manciple of the new monastery in Izamal and started setting up satellite missions. After all, the land cost them nothingthey had taken it from the Indios-and slave labor was easy enough to come by. Diego de Landa dressed in rough, woolen robes and personally monitored the education of the young Indios. Those converted to Christianity were soon filled with the same zeal as their master and destroyed the old shrines with the same enthusiasm that filled him.

Diego looked with great interest at the mighty buildings of T'ho, seeing them, however, only as sources of stone for the construction of the new Christian city of Merida. Thus the Maya temples became Christian cathedrals; the pyramids became the administration buildings for the Spanish rulers. Despite the fact that millions of polished stones were dragged to the new construction sites, Diego de Landa doubted that the "supply of buliding material could ever be exhausted."'

The holy zealot Diego de Landa was finally made provincial head of the order of Franciscans, before finally being made bishop of the new Christian city of Merida. It made him furious when he saw Mayans still clinging to their old culture and rites-when they were not prepared to let go of their old gods. Thus he gave the order to destroy all Mayan idols and writings. July 12, 1562, was certainly a day to remember: 5,000 icons, 13 altars, 192 ritual vessels, and 27 scientific and religious works, along with other illustrated manuscripts, were piled up in front of the church of San Miguel in Mani. At Diego de Landa's order, the whole pile was set alight. The flames licked, devoured, and consumed all of those irreplaceable documents of a grandiose culture. Ironically, the name of the city, Mani, translates as "it's over."

Unbothered by his act of cultural destruction, Diego de Landa noted: "We found a large number of books with illustrations, but these contained only lies and devilry. We burned them all, which sorely aggrieved the Maya causing them to sorrow greatly."3

That sorrow lasts to this day-and not only among Maya researchers, but also authors like me. If only we still had access to those old texts.... Then we wouldn't need to arduously scrabble around search for clues so that we can painstakingly revive the knowledge that existed thousands of years ago in Egypt and India, and hundreds of years ago in Central America, and that was part of the established wisdom of the scholars of those times-for instance, knowledge about the visits by genuine gods (= extraterrestrials) during the Stone Age.

The auto-da-f6 in Mani was just the start signal. In their blind zeal, the missionaries burned Maya manuscripts wherever they found them. Using the justification that it was "the Devil's work," Bishop de Landa destroyed every trace of Mayan culture that was connected to the gods, just like in Peru and Bolivia (see Chapter 1).

ayan Writings

ayan Writings

Despite this-and it's certainly a little joke of history-who do Maya researchers have to thank for delivering the keys to Mayan mathematics and the Mayan calendar? None other than the merciless Diego de Landa. For without him we would not know the Mayan calendar or its numerical system, and we would know nothing about the return of the gods. "How did that happen?" you ask.

Well, Bishop Diego de Landa-today he would be described as the hawk among the missionaries-somehow got caught in the firing line of the Spanish court. Informers brought back news to faraway Spain that Diego had even burned objects made of gold. Finding himself suddenly under pressure, Diego de Landa sought allies in the New World, allies who introduced him to the secrets of Maya knowledge. His teachers were the sons of the indigenous noble families. They were converts to Christianity and taught Bishop de Landa everything they had learned from their parents-one piece at a time. Diego de Landa noted everything down in Latin. He learned about the Mayan numeric system and the calendar, and also how their alphabet worked. And thus came about a veritable apologia with the title Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan-a report on things in the Yucatan.4 This text turned out to be a highly important source for Maya research. And it was rediscovered by pure chance.

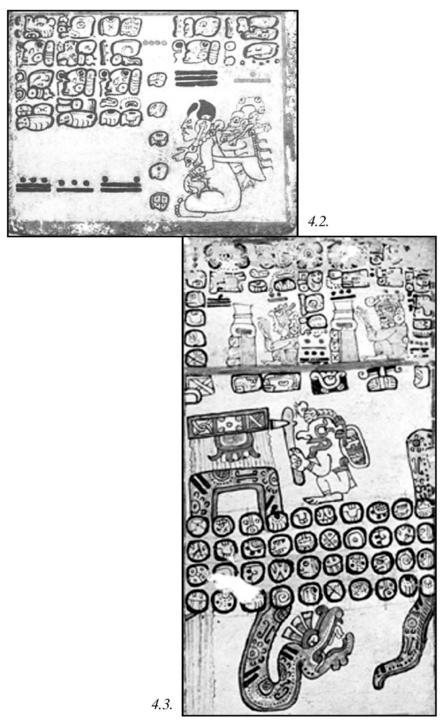

Three hundred years (!) later, Abbe Charles-Etienne Brasseur (1814-1874), a cleric working in the Royal Library in Madrid, discovered a rather unimposing document tucked between two gold-embossed folios. Brasseur, who himself had been a missionary for many years in Guatemala, was fascinated. Mayan glyphs and sketches stood out from the small, black Latin letters. In addition to these were a number of squiggles and short dashes, as well as short strokes placed over each other. By sheer coincidence, Brasseur had found the key that opened up the way out of the jungle of Maya numbers and letters.