Unlikely Warrior (4 page)

Authors: Georg Rauch

At the time I had but a vague understanding of what she was trying to tell me, realizing only that it was an idea very important to her. In the intervening years, however, she had made her point of view—her complete opposition to Hitler and all he represented—very clear.

That last morning, at the train station in Krumau, my mother and I walked back and forth for half an hour on the platform. None of the hundreds of soldiers sitting on straw in the cattle cars waiting to depart had any idea where the trip would end or whether they would ever return. It must have been obvious to most of them that their chances were slim at best. All one had to do was count up how many friends and relatives had been reported killed or missing in action during the past four years—that is, if they hadn’t returned home as cripples.

I was very impressed by two of the things my mother said to me that morning. I thought the first seemed easy enough to understand. She said, “Please remember something in the days to come. In case you don’t return, I won’t go completely to pieces. I will continue to live a full life, no matter what.”

To some this might sound strange, even cold, but with her words I could feel a great burden lifted from my shoulders, the burden of having to survive out there for my mother’s sake.

I wasn’t to understand her second remark until much later. She said, just as the train slowly started to move and I leaned down to give her a last kiss, “And remember, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

The train picked up speed steadily. By sticking my head out the sliding door of the boxcar, I could still see my mother, a slight, pale figure in a threadbare winter coat standing alone next to the tracks, her arm held motionless in the air.

Finally, she disappeared in the chilly morning fog. I knew that soon she would be on her way back to the town square, walking with that typical hurried step. She would be rushing to catch the next bus back to Vienna, for after all, the Jews hidden in the attic had to be fed and cared for, and life must go on.

The train rumbled through the night. We had taken two days to cross Czechoslovakia and Poland, with innumerable stops along the way. By now it had become all too clear that we were not heading for sunny Italy or a quiet duty in Scandinavia. No, our destination obviously had to be the most gruesome and life-consuming front of all—the Russian trenches.

In Czechoslovakia the train had passed through tidy little villages and towns. An occasional castle or fortress was perched on a hillside; country roads wandered here and there. We crossed a chain of mountains, and the landscape became flatter and increasingly dismal. Now we were traveling through western Russia on our way east.

Thirty men of all ages, dressed in the gray German infantry uniform, lay on the straw-covered floor of each of the boxcars. Most of them were either asleep or simply lying and thinking about what lay ahead. Each had his own story to tell, why and for the how-many-eth time he was on his way to the front. I doubted that many, if any, of my companions were eager to arrive at our destination, but perhaps some of them still cherished some sort of patriotic convictions? Well, I certainly didn’t share any of them.

I missed my training buddies of the past months and wondered whether I had anything in common with these strangers. So far, there had been no such indication. I spent most of my time in the corner, thinking over some of the unusual events of the past years and preferring to ignore the future.

The house where I grew up wasn’t one of the typical Viennese four- or five-story apartment buildings. My family lived on the top floor of a small

Stadtpalais

. It was one of a series of elegant mid-nineteenth-century buildings originally constructed to house individual families of the nobility. In our home, three large rooms had been constructed as an afterthought beneath the baroque copper roof. These rooms were fitted in among the attic storage areas, which were also generously proportioned but very irregularly shaped.

My

Tante

(aunt) Herta, who owned the building together with her daughter, son-in-law, and three grandsons, inhabited the floors below. We were all distantly related through my Jewish grandmother, Melanie Wieser, who had died before I was born, but no one in the house was a practicing Jew.

I had never had any reason to be particularly interested in my forefathers until a day shortly after the German takeover in Austria, when I came home from school and announced, “Tomorrow I have to take birth certificates and baptismal records of my four grandparents to school.”

“What for?” my mother wanted to know.

“Oh, it’s just something they have to check before accepting us into the Hitler Youth. They are going to give us all uniforms and special knives, and we’re going to go camping in the woods on the weekends.”

My mother stood there looking at me for a few moments. Then she went into the other room and returned holding a photo album.

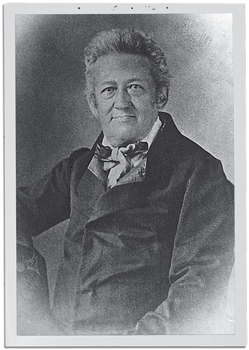

Baron Moses von Hönigsberg (1787–1875). Son of Israel von Hönigsberg, who was the first Austrian Jew to be knighted, by Kaiser Josef II in 1789.

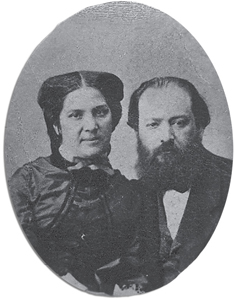

Luise Tauber and Josef Samuel Tauber.

Luise Tauber (1824–1894), born Baroness von Hönigsberg. She was Moses’s daughter and my great-grandmother.

Melanie Tauber with her two sisters, Luise and Henriette, at Professor Eisenmanger’s art school in Vienna.

My grandmother Melanie Amalie Tauber (1854–1908) at sixteen, in Vienna.

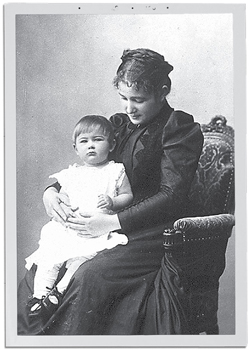

Melanie Tauber Wieser with my mother, Beatrix Wieser, in 1891.

“Come and sit down next to me,” she said. “I want to explain something to you.”

She opened the album and pointed to a small photo of an oil portrait. “This man was Baron Moses von Hönigsberg. His father was knighted by Kaiser Josef II in 1789. This is Moses’s daughter, Luise Tauber, born Baroness von Hönigsberg. She was your great-grandmother.”

There were many other pictures, all of extremely distinguished-looking persons, many of whom were in fancy uniforms. My mother told me about the positions of influence they had held during the monarchy and for what special deeds and services the Kaiser had raised them to the ranks of the nobility.

“All these I have shown you were your ancestors, and they were Jews. You have every right to be proud of them, and I hope you will never forget that. The reason you were asked to bring those official papers to school tomorrow is because they want to know whether you are a pure Aryan. That is, they want you to prove you have no Jewish blood. As you have just seen, you will be unable to do that.”

My thoughts were in a muddle. I was impressed with what she had shown me but also upset at the thought of becoming an outcast at fourteen.

“Well, what am I then?” I asked her.

“According to the traditions of our Jewish ancestors, you are a Jew, because your maternal grandmother was Jewish. In Hitler’s rulebook, though, a Jew who marries a non-Jew produces half-Jews. Since my father and your father’s family are Aryan, that makes you one-quarter Jewish, according to the Führer. Hitler has even coined a special word for people such as ourselves. One-half and one-quarter Jews are now called

Mischlinge

. I hope this isn’t going to make too many problems for you, but it’s something you’ll just have to get used to.”

* * *

During the following months it wasn’t all that easy for me to come to terms with my new status, or lack of one. I noticed that a number of my schoolmates began turning their backs on me, and even two or three of my teachers effectively ignored me. More and more of the boys my age were wearing the black corduroy shorts and brown shirts of the Hitler Youth and filling their free time with marching and practicing premilitary exercises. They appeared by the thousands at sports events and were also a common sight in the streets, their collection cans emblazoned with the letters

WHW

, which stood for

Winterhilfswerk

. No one was apt to challenge this claim of “winter help for the needy” or to ask where the large amounts of money collected actually went.

In one strange respect, my family turned out to have an advantage over many others. My father, Maximilian Rauch, had served as a captain in World War I and was called up for service again in 1939. Two days later, he was sent back home. The Germans could not permit a man who was married to a half-Jew to be a captain in the German army. Since my father had served honorably, however, they could not demote him to a lower rank. This strange set of bureaucratic circumstances led to the ironic result that he didn’t have to go to war at all; instead, he was assigned work as an engineer in a tool factory, Krause and Co.