Unlikely Warrior (8 page)

Authors: Georg Rauch

Russia, December 13, 1943

Dear Mutti,

Today I am in the happy position of writing you a letter full of satisfaction. Half an hour ago, completely filthy, lousy, and dog-tired, I climbed out of a hole in the ground that lay just 300 meters across from the Russians. They hadn’t anything better to do all afternoon than to keep trying to place a direct hit in my hole. It was pretty close a few times, but I got out with my bones intact after all.

This evening I said farewell to the trench, and in the future I’ll be working as a telegraphist. That pleases me very much, especially since it isn’t very nice having to shoot at Russians. The last few days weren’t nice at all. But enough of that. I have no idea how the future looks for me since it hasn’t yet been determined where I will be assigned as telegraphist. For certain it will be better in many respects, as I am now a member of the regimental headquarters staff.

I have overcome the 100 percent aversion to being here; or rather I had to overcome it.

A merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you and Papi.

Your Georg

I was assigned to a battalion headquarters that was situated in a village about three kilometers to the rear. Plodding through heavy snow, I arrived there on December 13. It was late, and I found a space to sleep on the floor of one of the houses.

The next morning I tottered out, stiff-limbed and still half-asleep, to wash off my face with snow. Somebody suddenly grabbed me from behind in a big bear hug and said, “Well, who would have believed it? Rauch has managed to survive his first ten days without suffering any depreciation!”

With that, Haas released me from his clinch and pulled my cap over my eyes.

“Hey, where are you detailed?” I asked him, grinning.

“Same firm, same team. Even the same hut.”

I was very happy to see him again. The realization that he was going to be nearby seemed to make the entire situation a lot friendlier.

Russia, December 14, 1943

Dear Folks,

Now I’ve become a human being again. A short time ago I arrived here at battalion headquarters, where I will be engaged as a telegraphist from now on. I like it tremendously! There are twelve of us telegraphists and phone operators living together in one hut, all very nice guys. The atmosphere is so friendly here, a relief from up front, where there is only yelling and complaining. What’s more, I have washed myself from head to toe and brushed my teeth. Yes, now the unpleasant part is all behind me. I can even hope to celebrate a halfway happy Christmas. Today, also, for the first time in a long while, I had a good laugh. That’s why I’m in a fantastic mood.

The food is excellent, because the Headquarters Company is feeding us. Schnitzel for lunch, schnitzel for supper, and sausage for breakfast. Meat in large quantities. The cook thinks to himself, whether we eat the pigs and calves today or the Russians eat them when we move on tomorrow, it is all the same. (Of course, it is not all the same to us.)

I feel like Adam, standing here naked, without possessions. The Russians have everything. I’ll just have to organize something. At any rate, I don’t have to worry much about the loading of my luggage when we are on the march. I feel particularly unburdened.

Outside it’s finally becoming bitter cold.

Pfirt Euch Gott

[May God watch over you] and go happy into the New Year. Many loving greetings,

Your Georg

Russia, December 21, 1943

Dear Mutti,

First of all, my best regards from Russia. Nothing has changed here for the last eight days. The daily monotony: up at six, Madka puts the potato soup with chicken on the table, it becomes light. One begins the first lice hunt. In every piece of clothing, twenty to thirty lice. Then the joint gets cleaned up. One man always sits at the switchboard and makes the connections. I am already pretty good at that. Mornings there’s nothing else to do.

At twelve-thirty we receive our warm lunch from the field kitchen and right after that they hand out the cold rations: sausage, butter, bread, and coffee. At two it starts to get dark, and you have to hurry up with another delousing or they’ll eat you alive.

In the afternoon I blow on the harmonica or write a letter. At five or six there’s chicken again. I can hardly bear to look at another chicken since, in addition to our military rations, which are plentiful and good, each of us eats approximately one chicken per day, and they are pretty fat in this part of the world.

Yesterday we also butchered a hundred-kilo pig. Meat, meat, and more meat. On that point we certainly can’t complain, but now and then you do miss something that tastes a little different from meat, potatoes, and bread.

At six we usually go to bed (which consists of a pile of straw and two blankets on the floor of the hut). But I’ve become used to it. At night each of us has two hours’ duty on the switchboard, but one doesn’t mind. First of all you aren’t very sleepy, and second the lice are biting like mad. Sometimes you think you will truly go crazy, and there’s not a thing you can do about it. And so one day passes like another.

Into the bargain, of course, one hears the eternal howling of the mortars, hits from bombs, bullets, and everything else that bangs and bursts around here. The main battle line is three kilometers away. Sometimes the Russians break through and come critically close. Then we also grab our guns and run out in counterattack to push them back. These occurrences are usually pretty bloody.

Except for food, the supply situation is pretty bad, because we’re sitting in a pocket that the Russians close up from time to time. In these cases, we have to exert ourselves to open it up again. For that reason not much is getting in. Incoming mail has begun functioning recently. I still haven’t heard anything from you, but I also have my third field post number. This one is the final one, however.

I have a couple of wishes that you might fulfill: three number-two pencils, some matches, four safety pins, a lighter and flint if possible, a map enlargement of the section with Alexandrovka and twenty-five kilometers west, a 1944 calendar diary, envelopes and paper, a paintbrush, and a mouth organ in C, since mine is broken or not working very well. These are all things I’m lacking.

I got back part of my luggage, mostly underwear. That’s why today is a holiday for me—I have on clean underwear with no lice! Please write me how much mail is getting through and when you receive it.

Many kisses from your Georg

The twenty-first of December was Stalin’s birthday, and all day long we could hear the drunken Russians shouting and shooting off their pistols. On the twenty-second and twenty-third they shot at us all day long with mortars and succeeded in wounding and killing quite a few. Haas convinced me that it was better to go without a helmet, because the German version was so heavy and came down so far over the ears that it made hearing almost impossible. And hearing well was vital. There was that sound of a soft blip that came from the Russian positions, the discharge from the mortars that one had to learn to take seriously. Approximately twenty seconds following that sound the hit landed, and it was much better to be prepared.

Russia, December 24, 1943

Dear Mutti,

Christmas in Russia, a rather strange feeling, especially when one is used to celebrating this holiday the way we do. But there is nothing to be done about that here. Nobody has the head for it. The Russians lie one hundred meters away, dug fast into the ground, and any minute they could come our way in great multitudes. Then there’s always uproar, shooting, wounded, dead, and afterward everyone sinks down somewhere or other and sleeps a couple of hours to recover. Who could still have the head for a Christmas celebration with presents, etc.? The soldiers are happy about the extra pack of cigarettes and bottle of schnapps that everyone gets. Some have received a package from home in time. Even just a greeting from home helps to a few peaceful thoughts.

Yesterday I went organizing here in the village. That is to say, one goes from hut to hut, pushing open the door, gun in hand. Then you rummage through the whole house without even tossing a glance at the inhabitants who are standing around and wailing, and you take whatever is worth taking. At first I didn’t have the heart for this, but in time you learn that, too. Thus I found eggs, butter, sugar, flour, and milk with which I baked a first-rate cake. Together with a little schnapps, it was a real treat. Afterward a few loving thoughts of you and Christmas 1943 was over. Well, one time like that for a change. Otherwise I’m doing great.

Your Georg

As delighted as I was to get out of the trenches, and especially out of the front fighting lines, being quartered a few hundred meters farther back, in a Russian house, was a mixed pleasure.

Very seldom did we encounter the solitary dwellings that one often sees in the Austrian countryside. The Russian houses were almost always grouped closely together in villages, each with its own vegetable garden and often a few fruit trees nearby. Usually the dwellings were uninhabited, evacuated, and at the soldiers’ disposal, but sometimes we shared the huts with very old people who hadn’t wanted or been able to evacuate, and even people with small babies.

The main building materials were sun-dried mud bricks to which a little chopped straw had been added. The ceilings consisted of thick, often sagging, smoke-blackened beams, over which boards were nailed. Outside the roofs were covered with straw and very steeply pitched so that the blankets of winter snow could slide off easily. The straw roofs, as well as the unbaked bricks, provided the perfect insulation against the harsh winters.

The wooden doors were so low that we average-sized Western Europeans always had to duck our heads upon entering. Windows were sparse and very small, but this aspect and the low ceilings were well thought out for keeping the houses pleasantly warm with only a minimum of heating materials, even during the bitterest of Russian winters.

Most of the huts had almost identical room arrangements. One entered a small vestibule through a door facing the square or street. Doors on the left and right of this hall led to the two main rooms. One of these served as living room/kitchen, with the large heating stove occupying one-quarter of the room space. The second, usually unheated room, which contained beds and a chest of drawers, was also used for storing clothing, tools, and seeds for the next planting season.

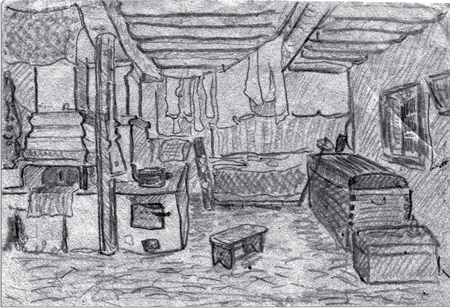

Russian village hut interior.

A ladder or very steep set of stairs rose from the entryway up to the attic, which often provided winter shelter for the chickens. A back door opened to the courtyard behind the house, where the horses, cows, pigs, and goats were quartered. The courtyard usually contained a deep well with a long rope and wooden bucket, a corncrib built on stilts to protect it from mice and dampness, and artfully piled stacks of straw and hay. Towering mounds of dried sunflower stems and cornstalks served as the only source of heating and cooking fuel, since neither wood nor coal was available in the immediate area.

At the back of the courtyard lay the vegetable garden, fenced in to protect it from the chickens and other thieves. Beyond this the fields stretched off onto the endless Ukrainian plain.

The spacious four-by-five-meter main room and the giant stove were the hub of the house, especially in winter. A bed, a few wooden trunks, a large rustic wooden table flanked by simple benches, and a number of low stools for accommodating tired feet or little children made up the humble furnishings.

The brick stove was very complicated and a wonder of heating and cooking technology. It jutted out from the walls by about two and a half meters on each side and had a main platform about sixty centimeters above the floor. Concentric, removable iron rings for the cooking pots and tea kettle lay on this surface, toward the center of the room, and iron bars formed a grill on some of the models. Sufficient platform space was still left over near the walls for sitting and warming one’s frozen bones after coming in from the cold on a wintry day.