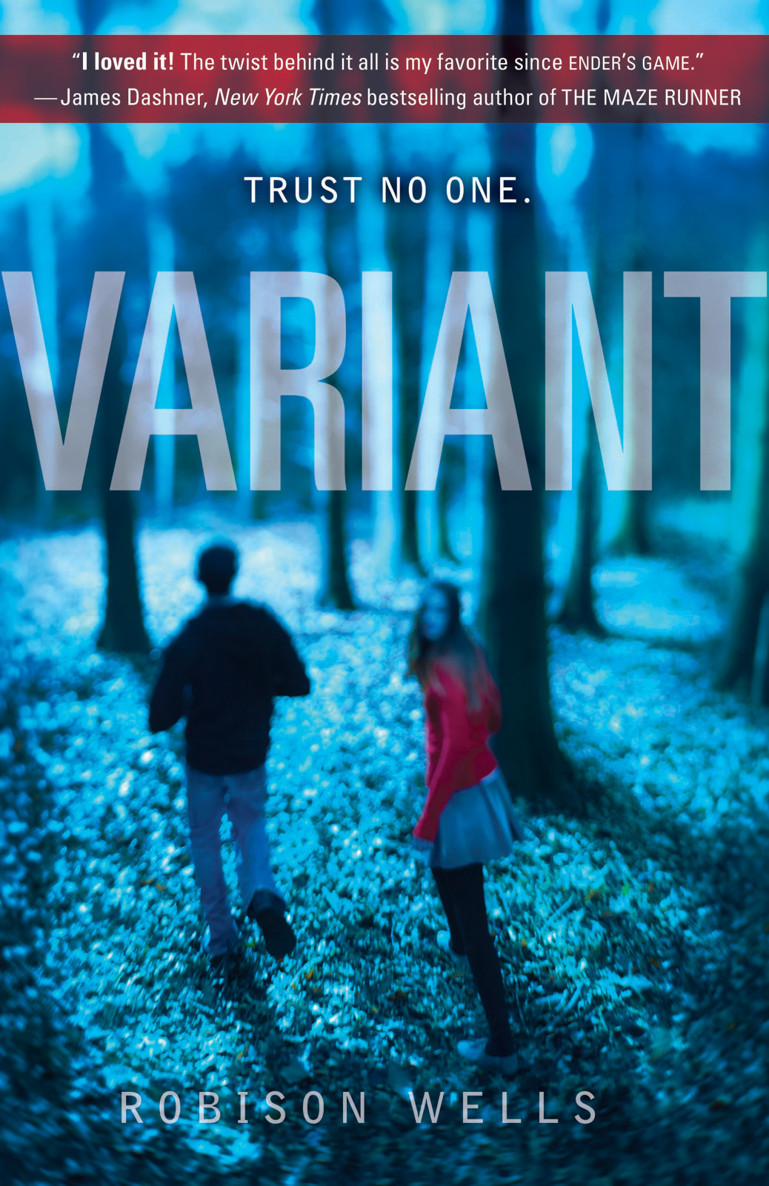

Variant

Authors: Robison Wells

VARIANT

ROBISON WELLS

To Erin, my best friend

Contents

T

his isn’t one of those scare-you-straight schools, is it?” I asked Ms. Vaughn, as we passed through the heavy chain-link gate. The fence was probably twelve feet tall, topped with a spool of razor wire, like the kind on repo lots and prisons. A security camera, mounted on the end of a pole, was the only sign of people—someone, somewhere, was watching us.

Ms. Vaughn laughed dismissively. “I’m sure you’ll be very happy here, Mr. Fisher.”

I leaned my head on the window and stared outside. The forest wasn’t like any I’d seen. Back in Pennsylvania, parks were green. Lush trees, bushes, and vines sprung up anywhere there was dirt. But these woods were dry and brown, and it looked like a single match could torch the whole place.

“Is there cactus here?” I asked, still gazing out at the trees. As much as I didn’t like this version of a forest, I had to admit it was better than what I’d expected. When I’d read on the website that Maxfield was in New Mexico, I’d pictured barren sand dunes, sweltering heat, and poisonous snakes.

“I don’t think so,” Ms. Vaughn said, not even bothering to look outside. “I believe you’d find cactus more in the southern part of the state.”

I didn’t reply, and after a moment Ms. Vaughn continued, “You don’t seem very excited about this. I assure you that this is a wonderful opportunity. Maxfield is the pinnacle of educational research. . . .”

She kept talking, but I ignored her. She’d been going on like that for close to three hours now, ever since she met me at the Albuquerque airport. She kept using words like

pedagogy

and

epistemology

, and I didn’t care much. But I didn’t need her to tell me what a great opportunity this was—I knew it. This was a private school, after all. It had to have good teachers. Maybe it even had enough textbooks for all the kids, and a furnace that worked in the winter.

I’d applied for this scholarship on my own. School counselors had tried to talk me into similar programs before, but I’d always resisted. At every school I’d attended—and there had been dozens—I’d try to convince myself that this one was going to be good. This was going to be the school where I’d stay for a while, and maybe play on the football team or run for office or even get a girlfriend. But then I’d transfer a few months later and have to start all over.

Foster care was like that, I guess. I’d racked up thirty-three foster families all around the city since I’d entered the program as a five-year-old. The longest had been a family in Elliott where I’d stayed for four and a half months. The shortest had been seven hours: The same day I showed up, the dad got laid off; they called Social Services and told them they couldn’t afford me.

The most recent family was the Coles. Mr. Cole owned a gas station, and I was put to work behind the counter on my first day. At first it was just in the late afternoons, but soon I was there on Saturdays and Sundays, and sometimes even before school. I missed football tryouts; I missed the homecoming dance. I never had a chance to go to any party, not that I’d been invited to one. When I asked to be paid for my work, Mr. Cole told me that I was part of the family, and I shouldn’t expect payment for helping out. “We don’t expect a reward for helping you,” he’d said.

So, I applied for the scholarship. It was part of some outreach thing, for foster kids. I answered some questions about school—I exaggerated a little bit about my grades—and I filled out a questionnaire about my family situation. I got the call the next afternoon.

I didn’t even show up at the gas station that night for my shift. I just stayed out late, walking the streets I’d grown up on, standing at the side of the Birmingham Bridge and staring at the city that I’d hopefully never see again. I didn’t always hate Pittsburgh, but I never loved it.

Ms. Vaughn slowed, and a moment later a massive brick wall appeared. It was at least as tall as the chain-link fence, but while that had looked relatively new, this wall was old and weathered. The way it spread out in both directions, following the contours of the hills and almost matching the color of the sandy dirt, it seemed like a natural part of the forest.

The gate in the wall wasn’t natural, though. It looked like thick, solid steel, and as it swung open, it glided only an inch above the asphalt. I felt like I was entering a bank vault.

But on the other side, the dehydrated forest kept on going.

“How big is this place?”

“Quite large,” she said with a proud smile. “I don’t know the exact numbers, but it’s very extensive. And, you’ll be pleased to know, that gives us a lot of room for outdoor activities.”

Within a few minutes, the trees began to change. Instead of pines, cottonwoods now lined the sides of the road, and between their wide trunks I caught my first glimpse of Maxfield Academy.

The building was four stories tall and probably a hundred years old, surrounded by a neatly mowed lawn, pruned trees, and planted flowers. It looked like the schools I’d seen on TV, where rich kids go and they all have their own BMWs and Mercedes. All this place was missing was ivy on the stone walls, but that was probably hard to grow in a desert.

I wasn’t rich so I wasn’t going to be like them. But I’d spent the plane ride making up a good story. I was planning on fitting in here, not being the poor foster kid they all made fun of.

Ms. Vaughn turned the car toward the building and slowed to a stop in front of the massive stone steps that led to the front doors.

She popped the automatic locks, but didn’t take off her seat belt.

“You’re not coming in?” I asked. Not that I really wanted to talk with her anymore, but I had kind of expected her to introduce me to someone.

“I’m afraid not,” she said with another warm smile. “I have many more things to do today. If I go inside, then we’ll all get to talking, and I’ll never get out of there.” She picked up an envelope from the seat and handed it to me. My name, Benson Fisher, was typed on the front in tiny letters. “Give this to whoever does your orientation. It’s usually Becky, I believe.”

I took the envelope and stepped out of the car. My legs were sore from the long drive and I stretched. It was cold, and I was glad I was wearing my Steelers sweatshirt, even though I knew it was too casual for this school.

“Your bag,” she said.

I looked back to see Ms. Vaughn pulling my backpack from the foot well.

“Thanks.”

“Have fun,” she said. “I think you’ll do very well at Maxfield.”

I thanked her again and closed the car door. She pulled away immediately, and I watched her go. As usual, I would be going into a new school all by myself.

I breathed in my new surroundings. The air smelled different here—I don’t know whether it was the desert air or the dry trees or just that I was far away from the stink of the city, but I liked it. The building in front of me stood majestic and promising. My new life was behind those walls. It almost made me laugh to look at the carved hardwood front doors when I thought back to the public school I’d left. The front doors there had to be repainted every week to cover up the graffiti, and their small windows had been permanently replaced with plywood after having been broken countless times. These were large and gleaming, and—

I noticed for the first time that the upper-story windows were filled with faces. Some were simply staring, but several were pointing or gesturing, even shouting silently behind the glass. I glanced behind me, but wasn’t sure what they meant.

I looked back at them and shrugged. In a second-floor window, directly over the front doors, a brown-haired girl stood holding a notebook. On it, covering the whole page, she’d drawn a large

V

and the word

GOOD

. When she saw that I had noticed her, she smiled, pointed at the

V

, and gave a thumbs-up.

A moment later, there was a loud buzz and click, and the front doors opened. A girl appeared, but she was pushed roughly out of the way as two other students—a boy and a girl—emerged, both wearing the uniform I’d seen on the website—a red sweater over a white shirt, and black pants or a skirt. The girl, who looked about my age or a little older, darted down the stairs, sprinting after Ms. Vaughn’s car. The guy, tall and built like a linebacker, grabbed my arm.

“Don’t listen to Isaiah or Oakland,” he said firmly. “We can’t get out of here.” Before I could even open my mouth he was gone, charging after the girl.

I

watched them run. They raced across the lawn, cutting through the manicured gardens without a pause, and disappeared into the trees. There was no way they were going to catch Ms. Vaughn, if that was their plan. I waited for a few moments, expecting them to reemerge, but they didn’t.

I turned and looked back up at the windows. Not everyone was wearing the uniform, but even the more casual clothes looked different from what teenagers had back home. Some seemed old-fashioned—buttoned-up shirts, suspenders, and hats—while others seemed like exaggerated costumes of rappers, all gold chains and bandanas. It was November—maybe they were a little late on Halloween. Maybe they were practicing a play.

I could see that some were still shouting. I raised my hands, gesturing that I couldn’t tell what they were saying.

The front door opened again, and a girl came out—the one who’d been shoved. She was grinning and carefree, like nothing had happened. She couldn’t have been a day over sixteen.

“You must be Benson Fisher,” she said. She stretched out her hand for me to shake it.

“Yeah,” I said, returning the handshake, even though it felt awkward. Teenagers aren’t supposed to shake hands. Maybe that was a private school thing, too. Her dad was probably some rich businessman.

“I’m Becky Allred. I do the new-student orientations.” She smiled widely, as though nothing was out of the ordinary. Her short brown hair was flawlessly waved and curled—it looked like a hairdo from old black-and-white movies.

I glanced down at the envelope in my hand. “So you’re the Becky I’m supposed to give this to?”

“Yep,” she said, taking it from me. “Your school records.”

I pointed up at the students in the windows, who were still staring down at us. “What’s going on up there?”

She waved up at them. “Nothing,” she said. “They’re just excited to see someone new.”

That seemed like an understatement. Some were even pounding on the glass now.

I forced a laugh to mask my confusion. “What’s the deal with those guys who ran?” I pointed back toward the forest. Neither of them had come back yet.

Becky’s smile never wavered, but her nose and eyes wrinkled. She thought for a moment before responding. “I think they’re just running,” she finally said. “I couldn’t really say why.”

She slipped her arm into mine and began to lead me up the stairs. She smelled good—like some kind of floral perfume.

Her answer wasn’t the explanation I wanted. She had to know more about the runners than she was letting on. I hoped it was a practical joke.

“Who are Isaiah and Oakland?” I asked.

She froze for an instant—almost imperceptibly—and then continued walking. “What do you mean?”

Whatever secret Becky was trying to keep, she wasn’t keeping it very well. Maybe this was some kind of hazing: Freak out the new guy.

“Isaiah and Oakland,” I repeated. “The runner guy said not to listen to them.”

Becky stopped and put her hands on her hips, turning toward me. Her smile was glued on her face, and she laughed almost like a real person. “Well, that’s about what I would expect from the two of them. Benson, I think you’ll find that this school has troublemakers, just like any other school. They’re trying to scare you. I mean, what do you expect from two people who are so blatantly breaking the rules?”

I nodded and took another step up the stairs. Her answer made sense. Maybe I’d worry about it if I met anyone named Isaiah or Oakland. What kind of name was Oakland, anyway?

Wait a minute.

“‘Breaking the rules’?” I asked, looking back at the forest. “How are they breaking the rules?”

Becky opened her mouth to speak, but no words came out. I watched her stammer for a moment and could feel my stomach dropping. Whatever was going on was stupid. Maybe I was the new kid who didn’t have a rich daddy paying my way, but I’d come to Maxfield to get away from the crap I’d put up with all my life in lousy schools. I wasn’t going to let a couple of snobby punks play mind games with me just because I didn’t have any money. I’d go talk to the principal.

I sighed and trotted the remaining steps up to the wooden door, but it didn’t open when I tried the handle. Becky followed, and when she reached me I heard the same buzz and click from earlier. She took the handle and pulled the heavy door open.

“They’re—” she began, paused, and then restarted. “No one is supposed to talk to new students before they’ve had orientation,” she said quickly. “It’s just one of the rules.”

I stood in the doorway and stared at her. She seemed unsure of herself. “That doesn’t make any sense. You’re not really Becky, are you?”

Her smile popped back onto her face. “No, I’m definitely Becky, and I’m definitely here to help you with orientation. That’s my job.”

“Your job?”

“We all have jobs here,” she said. “We do our part to help out, because we all rely on one another. We’re in this school so far away from everyone else—it’s like our own little society.”

“So I’ll have a job?” There was nothing on the website about that, and it felt a little bit like the Coles’ gas station.

“Of course,” she said. “We all have jobs.”

“Can you take me to talk to the principal?” It had felt a little weird before, but I was suddenly hit by the ridiculousness of talking to Becky about any of this. Ms. Vaughn had blathered something about students getting leadership opportunities, but I was sick of having the student body president—or whatever Becky was—give me a pep talk.

“Well,” she began, “why don’t we go to my office and do the orientation first. I’m sure that will answer some of your questions.”

“Let me explain something,” I said. “I’ve just been on a long flight and a long drive. I don’t feel well and I want to lie down. I don’t want orientation, because I know how a school works. I’ve been to a thousand schools in my life, and at every single one a counselor or secretary sits me down and tells me that I can join the Honors Society or the Science Club, and I already know that. Can we just go to the principal and do the real stuff?”

“The orientation is the real stuff,” Becky said. She again hooked her arm around mine and tried to get me to follow her, but I resisted. I probably had fifty pounds on her, in muscle and height, and I didn’t budge.

“I want to see the principal first.”

Becky’s face burst into a delighted smile, which was as fake as it was big. “You are so decisive. I think that’s terrific.”

“What?” I couldn’t believe how weird she was acting. Nothing in the orientation could be as important as she was making it appear. It was like she was trying to keep me

away

from the principal.

“I’m just saying that we can really use someone like you at this school.”

I laughed, though I didn’t know why. Maybe because this had to be a joke. “How old are you, Becky?”

“Sixteen, almost seventeen,” she said happily. “My birthday’s at the end of October.”

Her smile was plastered on like a tour guide’s. That’s what she was: a tour guide, all smiles and scripts.

“No offense,” I said, “but can you show me where the real Becky is?”

“What do you mean?” She let her hand slip off the door, and it swung slowly shut.

“I mean that I don’t believe a word you’ve said. This is all some stupid game.”

“I’m the real Becky,” she said, concern growing in her eyes.

“You’re not, and you’re not even a good liar. You said that your birthday is coming up at the end of October. It’s already November second.”

She opened her mouth but didn’t say anything. She took a step back and looked out at the forest. The two runners had just reemerged from the trees, their sweaters glowing a vibrant cherry red in the afternoon sun.

“So,” I continued, “enough of the crap.” I grabbed the door handle, but it was locked again.

“I am Becky,” she said, her arms folded across her chest.

“Why’s the door locked?”

“I am Becky,” she repeated.

“I don’t care,” I said. “How do we unlock the door? I want to see the principal.”

She turned to look at me, her eyes fierce. “I am Becky Allred. And I’m telling the truth.”

“I don’t care who you are. I want to see the principal.”

Her smile was gone now, replaced by a grim stare. “We don’t have one.”

What?

“We don’t have a principal,” she said. “We don’t have teachers, and we don’t have counselors. That’s why I do the orientations.”

“There’s no—I mean, you don’t have . . .”

She tried to put her smile back on, but it was weak and forced. “This school is different from other schools.”

“So who teaches the classes?”

“We do,” she said. “The students. We get lesson plans.”

“I don’t believe it,” I said. “That doesn’t explain your birthday. Why did you lie about that?”

Her grin seemed to be back in full strength. “It’s not a lie. I know it seems weird, and it’ll be easier to understand when we go through the full orientation. But . . .” She paused, mulling over her words. “We don’t have any calendars.”

“You’re kidding.”

“Nope.”

“Can’t you just look on your computers? Every computer has the date.”

“Not ours. But you do get your very own laptop. Did you know that?”

I couldn’t believe it—in spite of everything she’d just said, she was still trying to sell me on how great the school was.

“But can’t you just email someone? Get on the internet?”

Her nose wrinkled again. “Our computers don’t get on the internet.”

This was ridiculous. “Well, didn’t your family call you on your birthday?”

“No phones, either.”

“Let me get this straight. There are no adults in the school. And we can’t talk to anyone on the outside.”

She bobbed her head in embarrassed agreement.

I pointed at the two runners, who were standing on the lawn now, holding hands and looking back at the forest. I could see little puffs of breath rising from them as they talked.

“He said we can’t get out of here,” I said. “Is that true, too?”

“Yes.”

This could all still be a joke. It had to be a joke.

“I shouldn’t have taken the scholarship.”

“That depends on how you look at it,” she said. Her voice was warm and happy, but detached and distant, like she wasn’t really directing her words at me. Another script. “There are some great people in this school. We learn a lot of interesting things, and it can really be a lot of fun.”

I bet.

I wanted a good school and I got this. Ms. Vaughn had been right about one thing—she’d said this place would be different from what I was used to. I thought she’d meant that we’d actually learn something, and that kids wouldn’t get beat up in the parking lot. Instead, she meant that it was a prison.

“What’s the point of this place, then? Is it for screwed-up kids?”

Becky laughed. “No, it’s just a school. We go to class and we have dances and play sports.” She gave me a mischievous grin. “You’re not screwed up, are you?”

I pulled away from her, my confusion suddenly erupting into anger. “Why are you calm about this? How long has it been since anyone here has talked to anyone”—I gestured vaguely at the world beyond the forest—“out there?”

Becky glanced quickly at the horizon. The school sat in a low spot in the forest and we couldn’t see much more than the rolling, wooded hills and, in the far distance, a faded gray mountain range.

“I’ve been here for about a year and a half,” she said simply. “I don’t miss it. Like I said, things are good here.”

“Do people graduate?”

“Not yet,” Becky said. “But I don’t think anyone is old enough.” She took my arm again and turned me back toward the door. “How old are you?”

“Almost eighteen,” I lied, and then remembered that she had my records. “Well, I’ll be eighteen in about nine months. Happy birthday, by the way. You’re seventeen, too.”

Becky laughed and then stepped to the door. It unlocked again with a buzz, and she pulled it open. “I like you, Benson. You’ll do well here.”