Vermeer's Hat (5 page)

Authors: Timothy Brook

The Mohawks were the easternmost of five nations that had formed the Iroquois Confederacy in the sixteenth century and controlled

the entire woodland region south of Lake Ontario. The Mohawks were known as the eastern gate of the Iroquois and were charged

with protecting them on that flank—which exposed them to the arriving Europeans before any of their confederates. They were

eager to gain access to European trade goods, especially axes, and raided annually into the St. Lawrence Valley to acquire

them. Champlain called the Mohawks the “bad Irocois,” by way of contrasting them with the Hurons, whom he termed the “good

Irocois” (the Hurons spoke an Iroquoian dialect).

5

The Mohawk threat induced the Hurons, Algonquins, and Montagnais to revitalize an alliance among themselves to deal with this

threat. They were initially unsure how staunch their French allies would be, and suspected that, being traders, they might

have no great enthusiasm for going to war. Iroquet and Ochasteguin both confided to Champlain that a rumor had been circulating

during the hard winter of 1608 that the French were traders who had no interest in fighting.

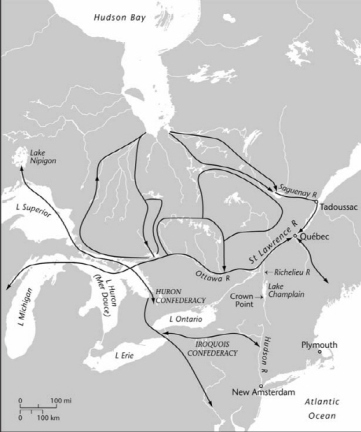

TRADE ROUTES IN THE GREAT LAKES REGION

Champlain challenged the rumor, assuring them it was untrue. “I have no other intention than to make war; for we have with

us only arms and not merchandise for barter,” he declared at their first meeting. “My only desire is to perform what I have

promised you.” He even returned the challenge. “Had I known what evil reports would be made to you, I should have held those

making such reports far greater enemies than your own enemies.” Iroquet and Ochasteguin graciously replied that they had never

believed the rumor, indeed had not even listened to it. Everyone knew they were talking about the Montagnais, who were not

happy to be losing their privileged access to French goods, but they shared a larger goal: attacking the Mohawks. The multinational

alliance set off on 20 June.

After part of the group split off to take their wives and trade goods back to Huronia, the war party consisted of twenty-four

canoes, each with three men. The French had brought along their own shallop, a two-masted riverboat that could seat ten rowers

plus a man at the tiller. The French traveled in the shallop, though Champlain preferred to join the Montagnais in their canoes.

That shallop soon became a problem. The party had to paddle up the Richelieu River toward Lake Champlain, but there were rapids

to ascend. The French boat was too heavy to go up the rapids and too awkward to portage. In the memoirs he wrote for public

consumption (and to gain financial support for his venture) in France, Champlain writes that he complained to the chiefs that

“they had told us the contrary of what I had seen at the rapids, that is to say, that it was impossible to pass them with

the shallop.” The chiefs expressed their sympathy for Champlain’s distress and promised to make up for it by showing him other

“fine things.” Ochasteguin and Iroquet had not been so ungracious as to tell him directly that bringing the shallop was a

bad idea. Better that he learn by his own experience rather than confront him and create ill feelings.

As the party went forward, scouts were sent ahead to look for signs of the enemy. Each evening as the light fell, the scouts

returned to the main party and the entire camp went to sleep. No one was put on watch. This laxity provoked Champlain, and

he made plain his frustrations with his Native allies.

“You should have men posted to listen and see whether they might perceive anything,” he told them, “and not live like

bestes

as you are doing.”

Bestes

, the old French spelling for

bêtes,

or “beasts,” might be better translated as “silly creatures,” or worse, “dumb animals.” A certain level of mutual linguistic

incomprehension probably insulated both sides from each other’s verbal barbs. In any case, the problem between them was not

just language. A sensible precaution from Champlain’s point of view was, from a Native point of view, nothing of the sort.

“We cannot stay awake,” one of them patiently explained to this exasperated European. “We work enough during the day when

hunting.”

The French military perspective could not grasp the logic at work in this situation: that one did only what one had to do,

not what one did not have to do. It was folly not to post guards when warriors from the Iroquois Confederacy were close, but

it was worse folly to waste precious energy posting them when the enemy was not within striking distance. Champlain imagined

warfare in other ways. He could not grasp that Natives organized warfare carefully, but differently from Europeans.

When they came within a day’s journey of Lake Champlain, the war party had to decide whether to forge ahead or turn back.

By then the Native warriors were devoting much attention to looking for signs not just of whether Iroquois were in the vicinity,

but of whether luck would be with them on this venture. Telling and listening to each other’s dreams was a means to detect

the future, yet no one had had a decisive dream. It was time to consult the shaman.

The shaman set up his spirit-possession wigwam that evening to divine the wisest course. Having arranged his hut to his satisfaction,

he took off his robe and laid it over the structure, entered it naked, and then went into a trance, sweating and convulsing

so violently that the wigwam shook with the force of his possession. The warriors crouched in a circle around the enchanted

wigwam, listening to his stream of unintelligible words that seemed be a conversation between the shaman’s own clear voice

and the croak of the spirit with whom he was speaking. They also watched for signs of spirit fire that might appear in the

air above the wigwam.

The result of the divination was positive. The war party should proceed. That decision made, the chiefs gathered the warriors

and laid out the order of battle. They placed sticks on a cleared piece of ground, one for each warrior, to show every man

what position he should take when the time for battle came. The men then walked through these formations several times so

that they could see how the plan worked and would know what to do when they met the enemy. Champlain liked the planning but

not the divination. The shaman he called a “wizard,” a “scoundrel,” a “scamp” who faked the entire production. Those who

attended the ceremony got the same contemptuous treatment. Champlain pictured them as “sitting on their buttocks like monkeys”

and watching the divination with rapt attention. He calls them “poor people” who were being deceived and defrauded by “these

gentlemen.” As he confides to his French readers, “I often pointed out to them that what they did was pure folly and that

they ought not to believe in such things.” His allies must have thought him spiritually stunted for his failure to grasp the

need for access to higher knowledge.

On one matter of divination, Champlain ended up compromising with local practices. His Native companions regularly asked him

about his dreams, as they asked about each other’s, and he was just as persistent in denying having any. But then he did.

His dream came when the party was only two or three days away from the moment of contact. By this point they were paddling

south on Lake Champlain, hugging its western shore and far enough south that the Adirondack Mountains were coming into view.

They knew that they were getting close to Mohawk territory and now had to travel by night, spending the daylight hours silently

hiding in the densest parts of the forest. No fire could be lit, no sound made. Champlain finally succumbed to dreaming.

“I dreamed that I saw in the lake near a mountain our enemies the Iroquois drowning before our eyes,” he declared when he

awoke and they asked, as they always did, whether he had had a dream. His allies were thrilled to receive this sign. When

he tried to explain that he had desired to save the drowning men in his dream, he was laughed at. “We should let them all

perish,” they insisted, “for they are worthless men.” Nonetheless, Champlain’s dream did the trick. It gave his allies such

confidence that they no longer doubted the outcome of their raid. Champlain may have been annoyed at “their usual superstitious

ceremonies,” as he puts it, but he was canny enough to cross the line of belief that separated him from them and give them

what they wanted.

As 29 June dawned and they set up camp at the end of a night of paddling, the leaders met to revise tactics. They explained

to Champlain that they would form up in good order to face the enemy, and that he should take a place in the front line. Champlain

wanted to suggest an alternative that would make better use of the arquebuses the French were carrying. It annoyed him that

he could not explain his battle tactic, which was intended not just to win this battle but to deliver a resounding defeat.

Historian Georges Sioui, a Wendat descendant of the Hurons, suspects that Champlain’s goal was to annihilate the Mohawks,

not just beat them in one battle. European warfare was not content with just humiliating the enemy and letting them run away,

which Native warfare could accept. Their purpose, phrased in our language, was to adjust the ecological boundaries among the

tribes in the region. Champlain’s goal, by contrast, was to establish an unassailable position for the French in the interior.

He wanted to kill as many Mohawks as possible, not to gain glory as a warrior but to prevent the Mohawks from interfering

with the French monopoly on trade. And he had the weapon to do this: an arquebus.

Champlain’s arquebus would be the hinge on which this raid turned, the stone that shattered the precarious balance among the

many Native nations and gave the French the power to rearrange the economy of the region. In 1609, the arquebus was a relatively

recent innovation. It was a European invention, although Europeans did not invent firearms; the Chinese were the first to

manufacture gunpowder and use it to shoot flames and fire projectiles. But European smiths proved adept at improving the technology

and scaling down Chinese cannon into portable and reliable firearms. The arquebus, or “hook gun,” got its name from a hook

welded to the carriage. The weight and unwieldiness of the arquebus made it hard to hold steady and take aim with any accuracy.

The hook allowed the gunner to suspend his weapon from a portable tripod, thereby steadying it before firing. The other way

to stabilize the arquebus was to prop it on a crutch that stood as high as the marksman’s eyes. By early in the seventeenth

century, gunsmiths were producing ever lighter arquebuses that could dispense with such accessories. Dutch gunsmiths got the

gun down to a marvelously light four and a half kilograms. The weapon Champlain carried was a gun of this lighter sort, French

rather than Dutch made but capable of being aimed without the impediment of a hook or crutch.

However streamlined an arquebus might get, firing was still cumbersome. The trigger was in the process of being invented in

1609. As of that date, an arquebusier still had to make do with a matchlock—a metal clip that held a burning fuse known as

a match to the gunpowder in the flashpan. When the arquebusier flipped the match down onto the flashpan, the gunpowder ignited

and burned its way through a hole in the barrel, causing the gunpowder charge inside the barrel to explode. (By the middle

of the seventeenth century, gunsmiths figured out how to build a trigger that was not prone to go off whenever the gun was

dropped, at which point the musket replaced the arquebus.) Despite its cumbersome firing mechanism, the arquebus redrew the

map of Europe. No longer did the size of an army determine victory. What mattered was how its soldiers were armed. Dutch gunsmiths

put themselves at the forefront of arms technology, providing the armies of the new Dutch state with weapons that were more

portable, more accurate, and capable of being mass-produced. Dutch arquebusiers ended Spain’s continental hegemony in Europe

and positioned the Netherlands to challenge Iberian dominance outside Europe as well. And French arquebusiers like Champlain

gave France the power to penetrate the Great Lakes region, and later to trim Dutch power in Europe.

The development of the arquebus was impelled by the competition among European states, but it gave all Europeans an edge over

peoples in other parts of the world. Without this weapon, the Spanish could not have conquered Mexico and Peru, at least not

until epidemics kicked in and devastated local populations. This technological superiority allowed the Spanish to enslave

the defeated and force them to work in the silver mines along the Andean backbone of the continent, mines that yielded huge

quantities of precious metal to finance their purchases on the wholesale markets of India and China. South American bullion

reorganized the world economy, connecting Europe and China in a way they had never been connected before, but it worked this

magic at gunpoint.

The magic of firearms had a way of slipping from European control when they entered metalworking cultures. The Japanese were

particularly quick to learn gunsmithing. The first arquebuses to enter Japan were brought by a pair of Portuguese adventurers

who had taken passage there on a Chinese ship in 1543. The local feudal lord was so impressed that he paid them a king’s ransom

for their guns and then promptly turned them over to a local swordsmith, who was manufacturing passable imitations inside

a year. Within a few decades, Japan was fully armed. When Japan invaded Korea in 1592, the invading army carried tens of thousands

of arquebuses into battle against the defenders. Had the Dutch not arrived with superior firearms that the Japanese were keen

to acquire, they would not have been allowed to open their first trading post in in Japan 1609—the very same year in which

Champlain demonstrated the power of his arquebus to the dumbfounded Mohawks. (Once Japan had come under a unified command,

its rulers chose in the 1630s to opt out of the vicious cycle of escalating firearms development by banning all further imports,

effectively imposing disarmament on the country, which lasted until the middle of the nineteenth century.)