Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison (33 page)

Read Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison Online

Authors: David P. Chandler

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Political, #Political Science, #Human Rights

BOOK: Voices From S-21: Terror and History in Pol Pot's Secret Prison

2.76Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

- Document 96 TS in DC–Cam archive. CMR 45.2, the confession of Kun, the wife of a senior cadre, is signed by two female interrogators named Ny and Li. The latter’s name appears in the telephone directory. For Ung Pech’s testimony, see Pringle, “Pol Pot’s Hatchet Man.” Vann Nath claimed that there had been a female interrogator at S-21 in 1978, but “she went crazy” (interview with author). Nath added that females were sometimes asked to witness interrogations of female prisoners to forestall sexual assaults. Seth Mydans, “A Cambodian Woman’s Tale,” is based on Mydans’s interview with a former female guard from S-21, Neang Kin, who, like Him Huy, was imprisoned briefly by the Vietnamese for committing atrocities at the prison. She confessed to these at the time but now denies them.

39. CMR 69.30.

- See, for example, CMR 86.25, Neou Puch.

- Confessions of documentation workers include CMR 3.24, Buth Heng; CMR 46.15, Keo Ly Thong; and CMR 106.11, Peng Leng Huoy.

- The negatives have been cleaned, processed, and catalogued by the Photo Archive Group, a nongovernmental organization set up in 1994 by the American photojournalists Douglas Niven and Chris Riley. See Niven and Riley,

The Killing Fields.

The photography unit also took snapshots of employees at the prison, according to Nhem En. Some of these snapshots, displayed in the East German documentary

Die Angkar,

have since disappeared, as have many of the photographs of dead prisoners shown in the film. - Interviews by author and Douglas Niven with Nhem En. See also McDowell, “Photographer Recalls Days behind Lens at Tuol Sleng.” For a reference to the “bad photographs,” see Chan notebook, uncatalogued DC–Cam document, entry for 26 December 1977.

- See CMR 99.8, “Ompi viney kapea khmang” (On the rules for guarding enemies). See also uncatalogued document from S-21 archive, dated 2 August 1976 (another set of rules), and author’s interviews with Him Huy, Vann Nath, and Kok Sros.

- Author’s interview with Kok Sros.

- CMR 98.8 lists thirty rules for guards. DC–Cam Document 1064, dated 31 October 1976, sets out some slightly different regulations. The rule about guards not observing interrogations is in an uncatalogued DC–Cam text dated 4 August 1976.

- For example, CMR 29.3, Eam Ron. According to Vann Nath, prisoners were sometimes beaten at random in the open spaces between buildings. See also Chameau, “No. 55 Delivers His Verdict,” and Todorov,

Facing the Extreme,

141. Todorov’s assertion that moral goodness was widespread among victims in the camps he writes about is impossible to document in S-21. With so few survivors, no inducements that prisoners could offer the staff, and poor material conditions nationwide, there is no evidence of bribery, special privileges, or friendships between prisoners and staff, and no S-21 workers ever confessed to such “offenses.” - Document D-1063, DC–Cam archive, dated 15 October 1976. The document closes by mentioning that only 258 prisoners were held at S-21 at the time. No confessions survive from any of the prisoners named in the text. Steve Heder suggests that procedures may have been tightened in the wake of Keo Meas’s incarceration in September 1976 (personal communication). The uniqueness of the document, clearly of a type that was prepared on a nightly basis, suggests that masses of documentary material prepared at S-21 have disappeared.

- CMR 17.24, Chey Pang, and CMR 29.3, Eam Ron, who confessed to depriving prisoners of food and beating some of them, for which they were made to carry excrement. For an example of a prisoner transferred to S-21 from Prey So, see CMR 20.4, Chhoeun Chek.

- On the economic support unit, see uncatalogued item in DC–Cam archive dated 18 July 1977. Duch’s report is CMR 99.10. The ducks and chickens, unlike the people, were of economic use.

- Uncatalogued item from Prey So in DC–Cam archive, dated 27 November 1977. See also CMR 80.28, Mam Bol, who was recaptured three days after escaping from Prey So, where he had been sent for deserting his military unit.

- See DC–Cam document 1116 TS, 7 March 1976, signed by Chan, listing “many” prisoners as seriously ill. See also the 1977 political notebook titled “Lothi Mak Lenin” (Marx-Leninism), uncatalogued item in S-21 archive, 38. See as well Chan notebook, 26 December 1977, for the accusation of Pheng Try. CMR 183. Va Sreng, a paramedic at S-21, confessed to taking a two-week course in microscopy before coming to work at S-21.

- CMR 106. 3, Phoung Damrei. See uncatalogued document from S-21 dated 2 March 1977: “4 people executed by taking blood.” Kiernan,

The Pol Pot Regime,

439, refers to a “tiny rectangular notebook . . . entitled ‘Human Experiments

(pisaot monus

)’” found near S-21 in 1979. Pages of the booklet are reproduced in

Die Angkar,

along with testimony from former S-21 workers that prisoners were occasionally bled to death. On other surgical experiments, Richard Arant (personal communication) cited an interview he conducted with a former Khmer Rouge cadre in 1996. - The class categories assigned to rural people in DK (“rich peasant”; two divisions of “middle peasant” and three divisions of “poor peasant”) had been borrowed from China via Vietnam without much regard for Cambodian conditions. See Carney, “The Organization of Power,” 99–100.

- Mao’s comment was made fi in 1956. See Starr and Dyer, comps.,

Post-Liberation Works of Mao Zedong,

173, and Moody,

Opposition and Dissent,

62. See also Bauman,

Modernity and the Holocaust,

writing in another context: “The combination of malleability and helplessness constitutes an attraction which few self-confident adventurous visionaries [can] resist. It also constitutes a situation in which they cannot be resisted” (114). - CMR 47.14, Kang Lean. The paragraph also draws on author’s interviews with Suong Soriya, Sieu Chheng Y, and Mouth Sophea, who were teenagers during the DK era.

- Talking to Alexander Hinton, the former guard Khieu Lohr noted that “Young people were often attached to cadres from the civil war when they were

very young [

touch,

literally ‘small’]. The cadre remained their patron

(me)

afterwards and brought the kids along to help [them] at the prison.” - See Gourevitch, “Letter from Rwanda,” 78–95, and his poignant and vivid book,

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families.

Mollica has worked extensively with Cambodian refugees in the United States. See also Ponchaud, “Social Change in the Vortex of Revolution,” which suggests that “Khmer revolutionaries modified what was at the core of Khmer society” (169). For a chilling study of U.S. Marines of the same age, see Solis,

Son Thang. - Minutes of Second Ministerial Meeting, 31 May 1976, document 705 in DC–Cam archive, 29. Pol Pot went on to say that young cadres in hospitals sometimes administered the wrong medicines because they were unable to read. He closed the meeting on an upbeat note, saying that “in three to five years we will be so powerful that enemies will be unable to do anything to us. We will have become a model for the world.” See also Document 1127, DC–Cam archive, undated youth meeting at S-21, which notes that young people at the prison are often lazy “and take advantage of meetings and study sessions to ‘enjoy themselves’” (literally “play,”

lenh

). - Quoted in Shawcross,

The Quality of Mercy,

334. - See Chandler,

Tragedy,

218–19, and Gibson, “Training People to Inflict Pain,” 72–87. The sorts of discipline and bonding that Gibson’s investigations revealed among military personnel in Greece in the 1970s are similar to those experienced by interrogators at S-21. - Ben Kiernan’s interview with Him Huy. On Khieu Samphan, see Heder,

Pol Pot and Khieu Samphan,

and Thayer, “Day of Reckoning.” - Douglas Niven’s interview with Nhem En.

- Douglas Niven’s interview with Nhem En, who said that the numbering system for prisoners in 1976–1977 was based on daily intakes, beginning with one at midnight every day. Several photographs show prisoners with tags numbered higher than 300. Starting in December 1978, prisoners were photographed with boards giving their names, the date of the photograph, and a number that placed them in a sequence begun each month.

- Note from Huy to Duch, December 1978, uncatalogued item in S-21 archive. See also document 1180, DC–Cam, listing twenty-four prisoners confined in the “special prison” in November and December 1978. Him Huy, talking to Peter Maguire, remembered that S-21 was to a large extent “cleared out” by the end of 1978. It is unclear from Ruy Nikon’s account whether all the “craftsmen” he mentions, who also figure in Nath’s memoir, were prisoners like himself or people brought in from outside the prison.

- See Locard, “Le Goulag des khmers rouges.” The large number of military prisoners accused of (or admitting to) petty offenses suggests that errant members of DK’s armed forces were held at S-21, a military facility, rather than in provincial prisons.

- Confessions of women enjoying high status in DK include those of CMR 26.3, Dim Saroeun; CMR 27.3, Ear Hong; CMR 41.8, Im Ly; CMR 61.25, Leng Son Hak; CMR 67.21, Lach Vary; CMR 116.20, Prun Ohal; CMR 165.11, Yaay Kon; and CMR 167.4, Tep Sam.

- Two of these, Von Vet and Sao Phim, had been deputy prime ministers of DK, the latter serving concurrently as secretary of the Eastern Zone. On the sequence of purges in DK, see chapter 3.

- Douglas Niven’s interview with Kok Sros. References to the “special prison” in the archive all date from 1978, but the photograph of Koy Thuon, a high-ranking cadre imprisoned in 1977, shows him chained to a metal bed (see photographs).

- Sofsky,

The Order of Terror,

153. - Hawk, “The Tuol Sleng Extermination Centre,” 26.

- Execution schedule for 2 June 1977, uncatalogued item from S-21 archive. For instances of sexual assaults on prisoners by prison staff, see CMR 17.3, Chea May; CMR 153.1, Sok Ra; and CMR 183.27, Vong Samath. Although documentation of sexual assaults on prisoners is rare, the dehumanization of the prisoners and the monastic conditions imposed on the staff would suggest that assaults were frequent.

- Foucault,

Discipline and Punish,

237. - Sara Colm’s interview with Vann Nath. See also Chameau, “No. 55 Delivers His Verdict,” which quotes Vann Nath: “During my first night I had some hope, but all my hope had gone away by the time morning came.”

- See People’s Republic of Kampuchea,

The Extermination Camp of Tuol Sleng. - Sara Colm’s interview with Vann Nath.

- CMR 22.8, Sun Heng; CMR 156.11, Suas Phon; CMR 169.17, Thai Peng; and CMR 174.6, Ton Tith. See also CMR 48.13, Khieu Son, in which Chan, after questioning, recommends further confinement but not execution. Kok Sros told Douglas Niven that “when the prison was at Ta Khmau, prisoners were sometimes released when they told the truth. Regulations were more relaxed then.” In

Die Angkar,

a document is cited that lists one prisoner, Duk Chheam, as “released” in 1976. I have been unable to locate this text in the archive. - Ashley’s interview with Vann Nath. The mock-up has not survived. The idea that Pol Pot should be depicted carrying a book of “revolutionary works” is ironic, since his speeches are almost devoid of references to written sources and were themselves never collected into a volume. The aim of the statue seems to have been to demonstrate the resemblances between Pol Pot and his revolutionary forebears, Mao Zedong and Kim Il Sung.

CHAPTER THREE. CHOOSING THE ENEMIES

- On Mao’s idea of permanent revolution, see Meisner,

Mao’s China and After,

206–16. See also Walder, “Cultural Revolution Radicalism.” Walder suggests that the values of the Cultural Revolution were “expressed in the framework of [a] conspiracy theory” (43). See also Starr and Dyer,

Post-Liberation Works of Mao Zedong.

“Enemies” at 120–22 is cross-referenced to “accom-plices, agents, alien class elements, bad elements, bandits, degenerates, lackeys, opponents, traitors to Marxism.” “Friends” is cross-referenced only to “contradictions,” 72. - Locard,

Petit livre rouge,

133. Vann Nath told Alexander Hinton: “That one word ‘enemy’ had great power. . . . Upon hearing the word ‘enemy’ everyone became nervous.” Hinton, “Why Did You Kill?” 113. The Cambodian verb

boh somat,

like the English word “clean,” has no negative connotations in ordinary speech and can refer simply to cleaning house. - For the text of the speech as it was delivered in 1957, see MacFarquhar et al., eds.,

Secret Speeches,

131–89. Pol Pot probably referred to the milder, authorized version when he mentioned the speech in his eulogy on Mao (FBIS, 20 September 1976). In the transcript of the speech (142–43), Mao admitted that in the

sufan

campaigns in 1950–1952, “We killed 700,000. . . . If they had not been killed, the people would not have been able to raise their heads. . . . The people demanded those killings in order to liberate their productive forces.” The last sentence could probably have served the Party Center in Cambodia as a justififor the massacres of “class enemies” in 1975, but not for the existence of S-21.

- Pol Pot, “Long Live the Seventeenth Anniversary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea,” FBIS, 4 October 1977. See also

Tung Padevat,

special issue, December 1975–January 1976, 41, which refers to “opportunists, accidental [revolutionaries] and those with . . . unclear biographies.”

Tung Padevat,

March 1978, translated in Jackson,

Cambodia 1975–1978,

speaks of “savage [reactionaries] who cannot be reeducated” (297). See also “Lothi Mak-Lenin,” undated notebook from S-21 archive: “The exploiting classes that were scattered and smashed in 1975 need to be scattered and smashed again” (59). For two stimulating discussions of political violence and the manufacture of enemies, see Merkl, ed.,

Political Violence and Terror,

28–29, and Apter, ed.,

The Legitimation of Violence,

1–20. - See Tucker,

The Soviet Political Mind,

55, which quotes Stalin in 1928 as saying, “We have internal enemies. We have external enemies. This, comrades, must not be forgotten for a single moment.” I am grateful to Steve Heder for providing this reference. - “CIA Plan,” uncatalogued document in Mam Nay’s handwriting from S-21 archive, dated 3 March 1976. The document asserts that “Son Ngoc Thanh’s [pro-American] forces and the Viet Cong have been allied for many years.”

- Document 1090, DC–Cam archive, “Essence of Interrogations of Soldiers Coming from the U.S.”

- Summers, “The CPK: Secret Vanguard,” 30. Pol Pot shared this fantastic view of the world. Speaking to Western journalists in December 1978, he informed them that only “NATO” could stop the planned invasion of Cambodia by troops affiliated with the “Warsaw Pact.” Becker,

When the War Was Over,

433–36. Similarly, according to the “Last Plan,” in Jackson,

Cambodia 1975–1978,

“the US used the Vietnamese [after 1975] with Soviet cooperation because the US had no troops to fight in Kampuchea” (312). - Locard,

Petit livre rouge,

166. See also Dittmer, “Thought Reform and Cultural Revolution,” which gives a Chinese quotation: “The enemies without guns are more hidden, cunning, sinister and vicious than the enemies with guns” (75). - Author’s interview with Seng Kan, a “new person” who was imprisoned for two years in Svay Rieng. See also Locard, “Le Goulag des khmers rouges,” and Etcheson, “Centralized Terror in Democratic Kampuchea.”

- Kiernan,

The Pol Pot Regime,

55–59, has a detailed discussion of this meeting, based on his interviews with participants. - Tung Padevat,

December 1975–January 1976, 41 (trans. Steve Heder). See also “Sharpen the Consciousness of the Proletarian Class,”

Tung Padevat,

September–October 1976, translated in Jackson,

Cambodia 1975–1978:

“The feudalists and the capitalist classes are . . . overthrown but their specific traits of contradiction . . . still exist in policy, in consciousness, in standpoint and class rage” (270). - “Pay Attention to Sweeping out the Concealed Enemies,”

Tung Padevat,

July 1978, 9–10. The passage schematically opposes an open, enlightened, wakeful, and resplendent CPK to the closed, dark, hidden, and burrowing forces arrayed against it. Some listeners may have been reminded fleetingly of the Buddha’s struggle with the evil forces of Mara. - Summers, “The CPK: Secret Vanguard,” 27.

- “Sharpen the Consciousness,” 273. See also “Abbreviated Lesson on the History of the Kampuchean Revolutionary Movement” in Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future:

“Contradictions between classes still exist . . . as standpoints, as attitudes, as self-interest” (222); and CMR 55.5, Kae San: “What can we see that’s weak about the revolution? It’s weak in that ideologically individualism is not yet gone. There’s still factionalism. There’s an ideology of unit, of organizationism. There’s an ideology of one’s own sector, there’s an ideology of one’s own zone, and simply of oneself.” These views are echoed in Zhang Chunqiao, “On Exercising All-Round Dictatorship over the Bourgeoisie,” an important article published in China in April 1975. See also Ling Hsaio, “Keep on Criticizing the Bourgeoisie.” Ironically, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot, atheists all, seem to have been drawn toward a doctrine that resembled the Roman Catholic dogma of original sin. At a more worldly level, if the struggle against enemies was permanent, so was the need for the enlightened leadership of the Party. When the people were still surrounded by enemies, how could the state wither away? - Locard,

Petit livre rouge,

175. The slogan was probably inherited from Vietnam. See Vo Nhan Tri,

Vietnam’s Economic Policy,

2–7, citing Vo Nguyen Giap from 1956. I am grateful to Steve Heder for this reference. The adage begs the question of how or by whom anyone’s innocence or guilt could be determined. Ironically, the ratio of “innocent” to “guilty” people executed at Tuol Sleng may well have reached ten to one. In Locard’s anthology, the saying appears alongside one that was frequently addressed to “new people” and is recalled by many survivors of DK: “Keeping [you] is no gain; losing [you] is no loss.” - On strategies, see “The Last Plan” in Jackson,

Cambodia 1975–1978:

“Pol Pot wanted to have everyone to be clean

(s’aat)

and pure

(borisut).

People who weren’t clean and pure were killed” (305). See also Pha Thachan’s interview with Lionel Vairon. On enemies as quintessential outsiders, see Giddens,

The Nation-State and Violence,

117. I am grateful to Zara Kivi Kinnunen for this reference. See also Kapferer,

Legends of People,

which argues that the Tamils in Sri Lanka, like “unbelievers”

(thmil)

in Cambodia, represent a subdued, demonic antithesis to the more widely accepted Theravada Buddhist “order.” - For a translation of this speech, see Chandler, Kiernan, and Boua,

Pol Pot Plans the Future,

183. See also Suárez-Orozco, “A Grammar of Terror,” 239, which cites an Argentine admiral in the 1970s who referred to death squads as “antibodies” combating the “germs” of radical dissent.

Tung Padevat,

April 1978, 39, has another microbe reference, and

Tung Padevat,

July 1976, “Whip up a Movement to Constantly Study the Party Statutes,” asserts: “The CIA attacks the revolution by injecting drugs into its veins” (51). - CMR 12.25 (trans. Steve Heder). See also Ponchaud,

Cambodia Year Zero,

40 ff. In 1988 Pol Pot told cadres that former Lon Nol personnel had been “smashed . . . because they represented imperialist strata” (Roger Nor-mand, personal communication). See also Heder interviews: “[The former Lon Nol officers] were asked to go and meet the Organization . . . and offered forgiveness but then were just taken away and executed” (46). Although there is abundant anecdotal evidence of these executions (see, e.g., Quinn, “Pattern and Scope of Violence,” 185 ff.), few documents recording the killings have survived. On propaganda encouraging the executions, see Ponchaud,

Cambodia Year Zero,

50–51. On the government’s curtailing the killings when they got out of hand, see Kiernan,

The Pol Pot Regime,

92. Mouth Sophea recalls a similar order reaching Khmer Rouge cadres in June 1975 in Battambang (author’s interview, February 1998). See also Vickery, “Democratic Kampuchea,” 109–10. In his “History of the Struggle Movement” (1997), Nuon Chea denied centralized responsibility. “As for the killing,” he wrote, “we didn’t know anything about it

[ot dung teng oh te].

It was the people lower down [

puok khang krom

] who behaved stupidly

[pdeh pdah].

” There is no record of any of these culprits being punished. - Chomsky and Hermann,

After the Cataclysm,

38–39 and 149. See also Aron,

L’histoire de l’épuration,

3 vols. (Paris, 1967–1975), and Marguerite Duras’s mordant vignette “Albert du Capitale.” The so-called White Terror in France in 1795–1796 and the 1965–1966 massacres of suspected Communists in Indonesia offer additional parallels. See Cribb, ed.,

The Indonesian Killings,

1–43. - On the Hanoi Khmer, see Kiernan,

How Pol Pot Came to Power,

319–21 and 358 ff., and Heder interviews, in which a former Khmer Rouge cadre recalled that in 1974 “it was said that all of those people who came from the North would... allow the Vietnamese to come back and control the country” (44). “The Last Plan” referred to them as “100 percent Vietnamese [who] had nothing left as Khmers” (Jackson,

Cambodia 1975–1978,

301). Other prisoners at S-21 documented from this period included malingerers, thieves, deserters, and foreigners who strayed onto Cambodian territory. People in these categories continued to be brought into S-21 until the collapse of the regime. Few of the earlier prisoners put a counterrevolutionary “spin” on their behavior. - Becker,

When the War Was Over,

274, and Arendt,

Totalitarianism,120.

- On the Siem Reap explosion, see Kiernan,

The Pol Pot Regime,

316–19, and Vickery,

Cambodia 1975–1982,

128. Intriguingly, the S-21 document “CIA Plan,” prepared a week later (see n. 6 above), failed to mention it, and a telegram to Son Sen from the acting secretary of the Northern Zone, Ke Pauk,

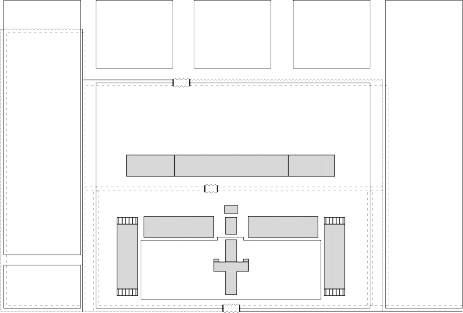

North

Killing field and burial ground

Former primary school: additional cells

B C

A D

E

Entry

Houses used for interrogation

A–D: Cells for mass-detention E: Administration and archive

Tuol Sleng Prison (S-21).

The Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocidal Crimes. Photo by Carol Mortland.

Kang Keck Ieu (alias Duch), the director of S-21. Photo Archive Group.

Staff photograph from S-21 (

1976

). Mam Nay (Chan) is in back row, at left; Duchis in back row, third from left. Women and children are unidentified. Photo Archive Group.

Other books

Stella Makes Good by Lisa Heidke

Keepers of the Flame (Trilogy Bundle) by Hart, Melissa F.

Oh Damn One Night of Trouble by Miller, Alice

Bring Forth Your Dead by Gregson, J. M.

Nailed by Jennifer Laurens

Building on Lies by T. Banny

Framed: A Psychological Thriller (Boston's Crimes of Passion Book 2) by Colleen Connally

The Secret Fate of Mary Watson by Judy Johnson