Volpone and Other Plays (5 page)

Read Volpone and Other Plays Online

Authors: Ben Jonson

Had I put an epigraph on the title-page, I should have adapted some words of Jonson's from the epilogue to

Cynthia's Revels, or The Fountain of Self-Love

:

By God 'tis good, and if you lik't, you may.

Falmer House

,                                                                                         M. S. J.

The University of Sussex

,

Brighton

St Bartholomew's Day, 1965

1.

BIBLIOGRAPHIES

W. W. G

REG

.

A Bibliography of the English Printed Drama to the Restoration

, 4 vols., 1940â59.

S. A. T

ANNENBAUM.

Ben Jonson (A Concise Bibliography)

, 1938.

S. A. and D

OROTHY

R. T

ANNENBAUM

.

Supplement to Ben Jonson, A Concise Bibliography

, 1947

SCHOLARLY WORKS OF REFERENCE

G. E. B

ENTLEY

.

The Jacobean and Caroline Stage

, 7 vols., 1941â68.

E. K. C

HAMBERS

.

The Elizabethan Stage

, 4 vols., 1923.

COLLECTED EDITIONS

The Workes of Benjamin Jonson

, 1616.

The Workes of Benjamin Jonson

, 2 vols., 1640.

C. H. H

ERFORD

and P

ERCY

and E

VELYN

S

IMPSON

, editors.

Ben Jonson,

11 vols., 1925â52.

A. B. K

ERNAN

and R. B. Y

OUNG,

general editors.

The Yale Ben Jonson,

in progress, 1962â.

BIOGRAPHICAL, CRITICAL, AND OTHER STUDIES

J. B. B

AMBOROUGH

.

Ben Jonson

, 1959.

J. A. B

ARISH

.

Ben Jonson and the Language of Prose Comedy

, 1960.

J. A. B

ARISH

, editor.

Ben Jonson: A Collection of Critical Essays

, 1963.

G. E. B

ENTLEY

.

Shakespeare and Jonson, Their Reputations in the Seventeenth Century Compared, 2 vols., 1945; The Swan of Avon and the Bricklayer of Westminster, 1946

.

M. C. B

RADBROOK

.

The Growth and Structure of Elizabethan Comedy

, 1955.

O. J. C

AMPBELL

.

Comicall Satyre and Shakespeare's âTroilus and Cressida'

, 1938.

M

ARCHETTE

C

HUTE

.

Ben Jonson of Westminster

, 1954.

T. S. E

LIOT

. âBen Jonson',

Selected Essays

, 1932; revised edition, 1951; reprinted by J. A. Barish, editor,

Ben Jonson: A Collection of Critical Essays

, 1963.

J. J. E

NCK

.

Jonson and the Comic Truth

, 1957.

D.J. E

NRIGHT

. âPoetic Satire and Satire in Verse: A Consideration of Ben Jonson and Philip Massinger',

The Apothecary's Shop

, 1957.

B

RIAN

G

IBBONS

.

Jacobean city comedy: A Study of Satiric Plays by Jonson, Marston and Middleton

, 1968.

A. B. K

ERNAN

.

The Cankered Muse: Satire of the English Renaissance

, 1959.

L. C. K

NIGHTS

. âBen Jonson, Dramatist',

The Pelican Guide to English Literature, 2, The Age of Shakespeare

, Boris Ford, editor, 1955;

Drama and Society in the Age of Jonson

, 1937.

H

ARRY

L

EVIN

. Introduction to

Ben Jonson: Selected Works

, n.d. [1938]; reprinted by J. A. Barish, editor,

Ben Jonson: A Collection of Critical Essays

, 1963.

E

RIC

L

INKLATER

.

Ben Jonson and King James: Biography and Portrait

, 1931.

R

OBERT

G

ALE

N

OYES

.

Ben Jonson on the English Stage, 1660â1776

, 1935

J

OHN

P

ALMER

.

Ben Jonson

, 1934.

E. B. P

ARTRIDGE

.

The Broken Compass: A Study of the Major Comedies of Ben Jonson

, 1958.

A. H. S

ACKTON

.

Rhetoric as a Dramatic Language in Ben Jonson

, 1948.

F

REDA

L. T

OWNSEND

.

Apologie for Bartholmew Fayre: The Art of Jonson's Comedies

, 1947.

W

ESLEY

T

RIMPI

.

Ben Jonson's Poems: A Study of the Plain Style

, 1962.

E

DMUND

W

ILSON

. âMOROSE BEN JONSON',

The Triple Thinkers

, revised edition, 1952; reprinted by J. A. Barish, editor,

Ben Jonson: A Collection of Critical Essays

, 1963.

OR

THE FOX

PRELIMINARY NOTE

1.

STAGE-HISTORY AND FIRST PUBLICATION

Volpone

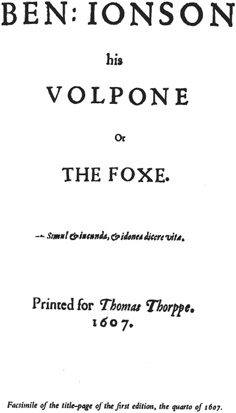

was first acted in late 1605 or early 1606 by the leading company of the times, the King's Men, led by Richard Burbage, who probably played Mosca with John Lowin as Volpone. It was successfully performed by them at Oxford and Cambridge. The play was published in quarto in 1607, prefaced by verse-eulogies from John Donne, George Chapman, Francis Beaumont, and John Fletcher, and was dedicated by Jonson âTo the Most Noble and Most Equal Sisters, the Two Famous Universities for their Love and Acceptance Shown to his Poem in the Presentation'. It was printed in the Folio

Workes

in 1616 and in the enlarged posthumous Folio of 1640. The play was regularly staged in London throughout the seventeenth and for most of the eighteenth century. After 1785 it does not seem to have been revived until the nineteen-twenties, when it was given two performances by the Phoenix Society and also played by Cambridge undergraduates. Donald Wolfit first appeared as Volpone at the Westminster Theatre in London in 1938, and included the play in several of his annual far-flung provincial tours in the forties. Sir Donald also appeared in the play on B.B.C. television. In 1952 Sir Ralph Richardson played Volpone at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon. Peter Woodthorpe was Volpone in the Marlowe Society production at Cambridge in 1955, when Jonathan Miller played Sir Politic Would-be. It was performed in modern dress under the direction of Joan Littlewood (who played Lady Would-be) by Theatre Workshop in 1955, a production more acclaimed in Paris than in London.

In 1926 Stefan Zweig made a German version, which was later translated into French by Jules Romains and played in Paris in 1928 by Charles Dullin in a multiple set by André Barsacq. This script was the basis of the memorable French film with Harry Baur as Volpone and Louis Jouvet as Mosca. Jean-Louis Barrault keeps the Zweig-Romains adaptation in his Parisian repertory.

Ruth Langner

actually translated Zweig's version back into English

for a Broadway production, with Alfred Lunt as Mosca, in 1928. José Ferrer appeared on Broadway in 1948 in Jonson's play; but the much-heralded production announced by Orson Welles in 1955 with himself as Mosca to Jackie Gleason's Volpone did not materialize. In 1964

Volpone

was seen at the new Tyrone Guthrie Repertory Theatre in Minneapolis, Minnesota, starring Douglas Cambell. An opera with music by Malcolm Williamson based on

Volpone

was seen in London in 1964, and in that year Bert Lahr appeared on Broadway in a musical

Foxy

, set in Alaska during the Gold Rush, and remotely inspired by Jonson's play. In 1965 John Neville played Mosca in a production at the Nottingham Playhouse. Leo McKern appeared as Volpone in Oxford and London in 1966â67 under the direction of Frank Hauser, a production which won more critical acclaim than Guthrie's for the National Theatre in 1968, when fussy business and good and bad ideas (animal costumes and movement; animal noises) blurred the lucid story-line.

LOCATION AND TIME-SCHEME

The action in

Volpone

takes place in Volpone's bedroom, inside and outside Corvino's house, in Sir Politic's lodging, in the Scrutineo, and in the street. The action covers one day, from Volpone's awakening (and Voltore's âearly visitation') to the sentences passed on Volpone and Mosca late in the afternoon.

EDITIONS AND CRITICAL COMMENT

Volpone

has been reprinted in various collected and selected editions of Jonson, and in many anthologies. It has been edited and annotated by J. D. Rea (1919), by Arthur Sale (1951), by David Cook (1962), and, as the first volume of the new Yale Ben Jonson, by A. B. Kernan (1962). J. J. Enck and E. B. Partridge have chapters on the play (the latter is concerned with imagery and what it tells us); J. A. Barish's compendium of Jonsonian criticism includes his own demonstration that Sir Politic and Lady Would-be are relevant to the play as a whole; and Professor Harry Levin has contributed a learned analysis of Mosca's interlude in 1, ii to

Philological Quarterly

, XXII (1943).

To the

Most Noble And Most Equal Sisters

,

The Two Famous Universities

,

For Their

Love and Acceptance Shown to His Poem

Ben. Jonson

,

The Grateful Acknowledger,

Dedicates Both It And Himself

.

10Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

There follows an Epistle, if

you dare venture on the length

.

Never, most equal Sisters, had any man a wit so presently excellent as that it could raise itself; but there must come both matter, occasion, commenders, and favourers to it. If this be true, and that the fortune of all writers doth daily prove it, it behooves the careful to provide well toward these accidents, and, having acquired them, to preserve that part of reputation most tenderly wherein the benefit of a friend is also defended. Hence is it that I now render myself grateful and am studious to justify the bounty of

20Â Â Â Â Â Â Â your act, to which, though your mere authority were satisfying, yet, it being an age wherein poetry and the

professors

of it hear so ill on all sides, there will a reason be looked for in the subject. It is certain, nor can it with any

forehead

be opposed, that the too much licence of poetasters in this time hath much deformed

their mistress

, that, every day, their manifold and manifest ignorance doth stick unnatural reproaches upon her; but for their petulancy it were an act of the greatest injustice either to let the learned suffer, or so divine a skill (which indeed should not be attempted

with unclean hands) to fall under the least contempt. For, if men

30Â Â Â Â Â Â Â will impartially, and not asquint, look toward the offices and function of a poet, they will easily conclude to themselves the impossibility of any man's being the good poet without first being a good man. He that is said to be able to

inform

young men to all good disciplines, inflame grown men to all great virtues, keep old men in their best and supreme state, or, as they decline to childhood, recover them to their first strength; that comes form the interpreter and arbiter of nature, a teacher of things divine no less than human, a master in manners; and can alone, or with a few, effect the business of mankind: this, I take him, is no subject

40Â Â Â Â Â Â Â for pride and ignorance to exercise their railing rhetoric upon. But it will here be hastily answered that the writers of these days are other things: that not only their manners, but their natures, are inverted, and nothing remaining with them of the dignity of poet but the abused name, which every scribe usurps; that now, especially in dramatic, or, as they term it, stage poetry, nothing but ribaldry, profanation, blasphemy, all licence of offence to God and man is practised. I dare not deny a great part of this, and am sorry I dare not, because in some men's

abortive features

(and would they had never boasted the light) it is over-true; but that all are

50Â Â Â Â Â Â Â embarked in this bold adventure for hell is a most uncharitable thought, and, uttered, a more malicious slander. For my particular, I can, and from a most clear conscience, affirm that I have ever trembled to think toward the least profaneness, have loathed the use of such foul and unwashed bawdry as is now made

the food of the scene

. And, howsoever I cannot escape, from some, the imputation of sharpness, but that they will say I have taken a pride, or lust, to be bitter, and not my

youngest infant

but hath, come into the world with all his teeth; I would ask of these supercilious politics, what nation, society, or general order, or state I