War: What is it good for? (49 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Détente collapsed. The United States rearmed furiously, deploying deadly new cruise missiles in Europe and talking up technologies that would slice through Soviet defenses like a knife through butter. Paranoia turned to panic in Moscow in 1982, when Israelis used American-made computerized weapon systems to destroy seventeen of Syria's nineteen Soviet-made surface-to-air missile sites and to shoot down ninety-two of its Soviet planes for the loss of three (or six, depending who was counting) of their own. And while any sensible scientist could have told the Soviets that decades would pass before “Star Wars” (an American system for shooting ICBMs down with lasers) or Assault Breaker (a long-range rocket that scattered masses of computer-guided bomblets to destroy entire armored divisions before they got to the front line) would actually work, in the febrile atmosphere of early 1980s Moscow, assuming the worst was a way of life.

It all came to a head in November 1983, just six weeks after Stanislav Petrov had had to decide whether to believe his own computer algorithm when it said that the Americans were launching their missiles. Convinced that NATO was planning a first strike, the neurotic, diabetic Soviet premier, Yuri Andropovâconfined to bed by his failing kidneysâpressured the KGB to find evidence of it. Ever dutiful, his spies reported back that a lot of American and British civil servants seemed to be working late in their offices. The only possible conclusion: the United States must be planning to use an upcoming military exercise in western Europe as cover for an attack. Soviet aircraft in East Germany were armed with live nuclear weapons. Leave was canceled. Even military weather forecasts were suspended, lest they give something away.

Fortunately, the one sure thing in the Cold War was that no one could keep a secret. “When I told the British,” a senior KGB officer later reminisced to interviewers, “they simply could not believe that the Soviet leadership was so stupid and narrow-minded as to believe in something so impossible.” Opinions vary as to whether Andropov really was this stupid and narrow-minded, but American fear of Soviet fear reached the point that Reagan felt the need to dispatch General (later National Security Adviser) Brent Scowcroft to Moscow to persuade Andropov to step back from the brink.

Once again, millions marched to ban the bomb. Bruce Springsteen released his remake of “War.” Anyone not worrying about the end of the world was not paying attention.

And yet here we are, thirty years on, safer and richer than ever. Against all the odds and in defiance of the trends of the last ten thousand years, the war to end warâand humanity itselfâdid not come. For every twenty nuclear warheads threatening our survival when Petrov picked up the phone in 1983, there is now (in mid-2013) just one. The chance of a megawar killing a billion people in the next few years seems close to zero.

How did we make it through these dangerous days? And how long will our luck hold out? These, it seems to me, are among the most important questions anyone can ask. The answers, though, lie in a place we rarely look.

Footnote

1

That is, raise the trajectory of the barrel slightly.

6

RED IN TOOTH AND CLAW: WHY THE CHIMPS OF GOMBE WENT TO WAR

Killer Apes and Hippie Chimps

January 7, 1974

In the early afternoon, a war party from Kasekela slipped unseen across the border into Kahaman territory. There were eight raiders, moving silently, purposefully, on a mission to kill. By the time Godi of Kahama saw them, it was too late.

Godi leaped from the tree where he had been eating fruit and ran, but the attackers fell on him. One pinned Godi facedown in the mud; the others, screaming with rage, punched and tore at him with their fangs for a full ten minutes. Finally, after hurling rocks at his body, the war party headed deeper into the forest.

Godi was not dead, yet, but blood was pouring from dozens of gashes and punctures in his face, chest, arms, and legs. After lying still for several minutes, mewling in pain, he crawled into the trees. He was never seen again.

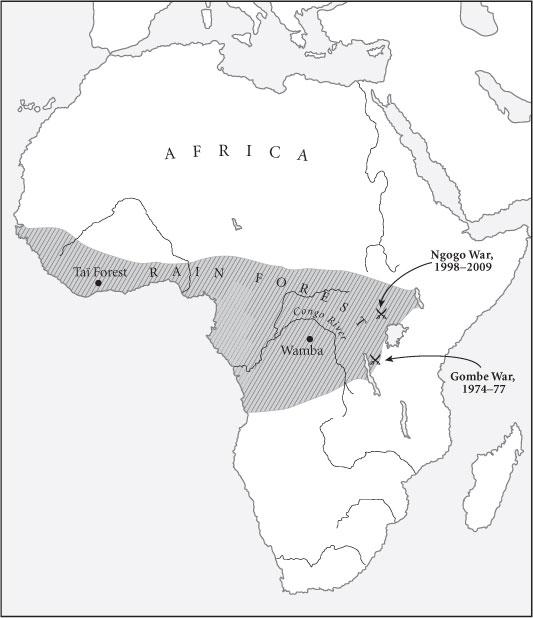

This was the first time that scientists had seen chimpanzees from one community deliberately seek out, attack, and leave for dead a chimpanzee from another. In 1960, Jane Goodall had set up the world's first project to study chimpanzees in the wild at Gombe in Tanzania (

Figure 6.1

), and for a decade she had delighted readers of

National Geographic

and viewers of her television specials with stories of the gentle, wise David Greybeard, the canny Flo, the mischievous Mike, and all their chimpanzee friends. But now the chimps were revealed as murderers.

Figure 6.1. The cradle of war: sites in Africa mentioned in this chapter

Worse followed. Over the next three years, the Kasekelans beat to death all six males and one female in the Kahama community. Two more Kahaman females went missing, presumed dead; three more, beaten and raped, joined the Kasekelans; and finally, the Kasekelans took over Kahama's territory. Godi's death had been the first blow in a war of extermination (

Figure 6.2

).

Figure 6.2. Killer apes? Four chimpanzees (at left) bully, threaten, and charge a fifth chimpanzee (at right) in the primate park at Arnhem Zoo in the Netherlands (late 1970s).

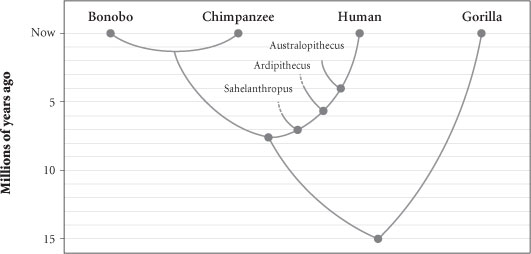

News of the Gombe War rocked the world of primatology. The implications, it seemed, were enormous. We humans share more than 98 percent

of our DNA with chimpanzees. When two closely related species behave in the same way, there is always a good chance that they have inherited this trait from a shared ancestral species. Since we only have to go back 7.5 million years (not long to an evolutionary biologist) to find the last common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans, the obvious conclusion seemed to be that humans are hardwired for violence.

The 1970s were the golden days of

Coming of

Ageism, and, not surprisingly, this finding did not sit well with everyone. Some scholars blamed the messenger. Goodall, they insisted, had caused the war. In her efforts to get the chimpanzees comfortable around humans, she had fed them bananas, and competition over this rich food, the critics suggested, had corrupted the chimps' naturally peaceful society and turned it violent.

The ensuing debate was just as bitter as the quarrels I described in

Chapter 1

over the anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon's account of the fierce Yanomami, but Goodall did not have to wait as long as Chagnon to be proved right. In the 1970s and '80s, dozens of other scientists plunged into the African rain forest to live among apes (my account of the Gombe War and much else in the opening section of this chapter draws on the book

Demonic Males

that one of these scientists, Goodall's former graduate student Richard Wrangham, co-authored with Dale Peterson). Developing more sophisticated, less intrusive methods of observation, they soon showed that chimpanzees wage war whether humans feed them or not.

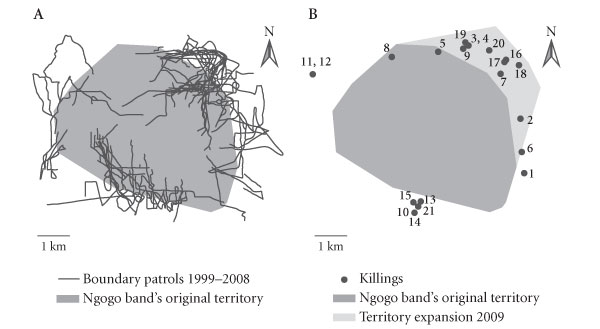

Even as you read these words, gangs of male chimpanzees are patrolling the boundaries of their territories everywhere from the Ivory Coast to Uganda, systematically hunting for foreign chimps to attack. They move silently and deliberately, not even taking time to eat. The most recent study, in Uganda, used GPS devices to track dozens of raids and twenty-one kills made by the Ngogo chimpanzee community between 1998 and 2008, ending in the annexation of a neighboring territory (

Figure 6.3

).

Figure 6.3. The Ngogo War, 1998â2009. Ngogo chimpanzees launched dozens of raids into neighboring territories (black lines on the map at left), killing twenty-one chimpanzees before annexing the area that had seen the heaviest fighting (shaded area on the map at right).

The chimps' only weapons are fists, teeth, and the occasional rock or branch, but even an elderly chimp can hit harder than a heavyweight boxer, and their razor-sharp fangs can be four inches long. When they find enemies, they fight to kill, biting through fingers and toes, breaking bones, and ripping off faces. On one occasion, primatologists looked on in horror as attackers tore open their victim's throat and yanked out his windpipe.

So

Lord of the Flies

would seem to have gotten it right: the Beast is part of us, close, close, close. But, as usually happens in new scientific fields, it quickly turned out that things were more complicated. When I brought up the

Lord of the Flies

theory in

Chapter 1

, I immediately had to add that a trip across the South Seas to another island, Samoa, put things in an entirely different perspective. There, Margaret Mead found evidence that convinced

her that she had stumbled onto a Pacific paradise, where violence rarely reared its ugly head. In a similar way, if we leap six hundred miles across the mighty Congo River from Gombe to a different patch of African rain forest, called Wamba, it feels as if we have followed Alice through the looking glass into Wonderland.

On December 21, 1986, the primatologist Gen'ichi Idani was sitting at the edge of a clearing. He was waiting to see a party of apes pass through, but to his astonishment, not one but two parties simultaneously showed up. If Idani had been at Gombe, things might have turned very nasty in the next few minutes. There would have been threatening hoots between the parties, followed by mock charges and branch-waving. Under the wrong circumstances, there might have been fighting and death.

At Wamba, though, none of that happened. The two parties sat down a few yards apart and stared at each other. After half an hour, a female from what the primatologists were calling the P-group got up and ambled across the open ground toward a female from the E-group. A moment passed, and then the two females lay down facing each other. Each spread her legs; they pressed their genitals together. They started moving their hips from side to side, faster and faster, rubbing their clitorises together and grunting. Within minutes both apes were panting and shrieking, hugging each other tightly, and going into spasms. For a tense moment both fell silent, staring into each other's eyes, and then they collapsed, exhausted.

By this point, the distance between the two parties had dissolved. Almost all the apes were sharing food, grooming, or having sexâmale with female, female with female, male with male, young with old, with hands, mouths, and genitals mingling indiscriminately. They were making love, not war (

Figure 6.4

).

Figure 6.4. Hippie chimps: two female bonobos in the Congo Basin engaging in what scientists call genito-genital rubbing

Over the next two months, Idani and his colleagues watched the P- and E-groups repeat this scene some thirty times. Not once did they see anything like the violence of the Gombe chimpanzeesâbut that was because the apes of Wamba were not chimpanzees. Not the same kind of chimpanzees, anyway. Technically, the Wamba apes were pygmy chimpanzees

(Pan paniscus),

while the Gombe apes were regular chimpanzees (Pan

troglodytes

).

To the untrained eye the two species are almost indistinguishable, the pygmy variety being just slightly smaller, with arms and legs a little longer and thinner, mouths and teeth a little smaller, faces a little blacker, and hair parted in the middle (primatologists only identified

Pan paniscus

as a

separate species in 1928). The differences between them, though, help us answer the fundamental question of what war is good for, and what will happen to humanity in the twenty-first century.

Pygmy chimpanzees (to avoid confusion, scientists usually call them bonobos; journalists often call them hippie chimps) and regular chimpanzees (usually just called chimpanzees, without any qualifying adjective) have almost identical DNA, having diverged from their shared ancestor just 1.3 million years ago (

Figure 6.5

). Even more surprisingly, the two kinds of apes are genetically equidistant from humans. If chimpanzee wars suggest that humans might be natural-born killers, bonobo orgies suggest we could equally well be natural-born lovers. Rather than pulling out their swords and stabbing at the Graupian Mountain, Agricola and Calgacus might have torn off their togas and rubbed their genitals together.

Figure 6.5. The family tree: the divergence of the great apes from our last shared ancestor fifteen million years ago