War: What is it good for? (52 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Once again, food seems to have been at the center of things. Because fruit trees thin out in these dry borderlands, giving way first to mixed woodland and then to open savannas, apes had to find new things to eat if they were to live there. Since adversity is the mother of evolutionary invention, all kinds of genetic mutations flourished as the apes adapted. Anthropologists have given these creatures wonderful, exotic namesâ

Sahelanthropus

north of the rain forest,

Ardipithecus

east of it, and different kinds of

Australopithecus

all around itâbut I will call them collectively protohumans.

To the nonexpert eye, protohuman bones look much like any other ape's, but great changes were under way. Over a few million years, molar teeth grew bigger and flatter, thickly coated with enamel. This made them ideal for crunching up hard, dry foods, and chemical analysis shows that the foods in question were tubers and the roots of grasses. These are good sources of carbohydrates and are available even in dry spells, when the aboveground parts of plants shrivel upâ

if

apes can dig them up and chew them. Any mutation that made paws nimbler would therefore make protohumans fatter, stronger, and probably better at fighting too, and altogether more likely to spread their genes through the population.

The anatomy of ankles and finds of actual footprints, left by protohumans taking strolls through soft ash and mud that then hardened into stone, show that the shift was under way by four million years ago. Protohumans had begun walking on their hind legs, freeing up their front legs to turn into arms. These creatures were certainly still very different from us, however. They were only four feet tall, probably covered in hair, and still spent a lot of time in trees. They rarelyâif everâmade stone tools and certainly could not talk, and it is a fair bet that the males still had testicles on the chimpanzee/bonobo scale.

But however apelike they were, they more than made up for it by mutating toward bigger and bigger brains. Four million years ago, the average

Australopithecus

sported twenty-two cubic inches of gray matter (less than modern chimpanzees, which typically have twenty-five cubic inches). By three million years ago, this had increased to twenty-eight cubic inches, and another million years after that, to thirty-eight. (Today we average eighty-six cubic inches.)

It might seem self-evident that big brains are better than small ones, but the logic of evolution is more complicated. Brains are expensive to run. Our own typically make up 2 percent of our body weight but use up 20 percent of the energy we consume. Mutations producing bigger brains only

spread if the brain tissue that is added pays for itself by bringing in the extra food it needs. In the middle of the rain forest, this was rarely the case, because apes did not need to be Einsteins to find leaves and fruit. In the dry woodlands and savanna, however, brainpower and food supply rose together in a virtuous spiral. Smart woodland apes dug up roots and tubers, which paid for bigger brains; the even smarter apes this produced figured out better ways to hunt, and meat paid for even more of the expensive gray cells.

Armed with all this brainpower, protohumans went straight to work on inventing weapons. Modern chimpanzees and bonobos have been known to use sticks and stones to catch food and hit each other, but by 2.4 million years ago protohumans had already realized that they could bash pebbles together to make sharp cutting edges. Telltale marks show that they used these choppers (as archaeologists call them) to slice meat off animal bones, although so far we have found no signs that they used them to slice each other.

Biologists conventionally treat the combination of brains over thirty-eight cubic inches and the ability to make tools as the threshold at which apes became

Homo

(“mankind” in Latin), the genus to which we,

Homo sapiens

(“wise man”), belong, and over the next half-million years

Homo

began looking and acting much more like us. Around 1.8 million years ago, in the space of a few thousand generationsâthe blinking of an evolutionary eyeâaverage adult height shot up above five feet. Bones became lighter, with jaws that protruded less and noses that protruded more. Sexual dimorphismâthe size difference between males and femalesâdeclined toward the range we find among modern people, and protohumans shifted permanently from tree to ground living.

The label that biologists use for these new creatures is

Homo ergaster,

“working man,” chosen to reflect their skill at making tools and weapons. Some of these can be quite beautiful, made from carefully selected stones and finished with delicate touches from wood and bone “hammers”âall of which required careful coordination, forward planning, and, of course, bigger brains still (fifty-three cubic inches by 1.7 million years ago).

Homo ergaster

paid for its huge head with a peculiar trade-off: its guts got smaller. Earlier protohumans had rib cages that flared out at the bottom, like those of modern apes, to accommodate enormous intestines, but

Homo ergaster's

ribs were more like ours (

Figure 6.8

). This left less room for yards of digestive tubing, which poses a difficult question for anthropologists. Apes have huge bowels so they can digest the fibrous raw plants

they live on. Smaller guts would mean that

Homo ergaster

was extracting less energy from its foodâbut its bigger brain called for

more

energy. So what was going on?

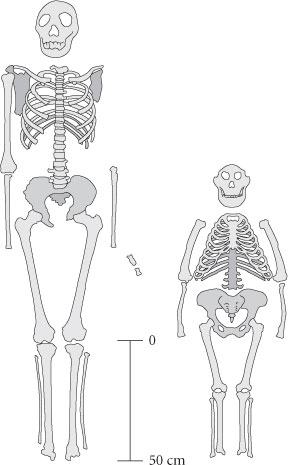

Figure 6.8.

La bella figura

: on the left, the best-preserved

Homo ergaster

skeleton so far found (known as the Turkana Boy), belonging to a boy roughly ten years old who died 1.5 million years ago; on the right, the famous Lucy, an adult female

Australopithecus afarensis

who lived 3.2 million years ago

The answer, we can be fairly certain, is that

Homo ergaster

was the first protohuman that could make fire at will and used this new skill to cook. Cooking makes food easier to digest, which made enormous intestines, along with the huge flat teeth and powerful jaws earlier protohumans had needed to chew up raw tubers, roots, and grass, redundant. All now disappeared.

This, Richard Wrangham suggests in his marvelous book

Catching Fire,

was as much of a turning point in the evolution of human violence as snacks were for bonobos. Anytime a chimpanzee catches a monkey or finds a particularly tasty breadfruit, Wrangham has observed in his many years

in the rain forest, males materialize from all around, and fighting frequently breaks out. Even sweet-natured bonobos find it difficult to enjoy a morsel of monkey brain without being besieged by jostling beggars. It is hard, Wrangham observes, to imagine how either kind of ape could have cooked food without it all being stolenâin which case this adaptation would not have paid off and would not have spread through the population. This forces us to conclude, Wrangham suggests, that when cooking caught on, it did so as part of a package deal with another great changeâthe shift from living in large, sexually promiscuous troops (like chimpanzees or bonobos) to male-female pair-bonding.

When chimpanzees and bonobos look for food, it is every ape for itself, with males and females active as both hunters and gatherers. Among modern human hunter-gatherers, though, men typically do nearly all the hunting and women nearly all the gathering, and they then share the food with each other and their offspring. The details vary according to where in the world people live, but in pretty much every hunter-gatherer society, woman's work includes cooking and man's work includes threatening or even attacking anyone trying to steal the couple's food. This raises the costs of theft, changing the evolutionarily stable strategy. Families replace troops as the foundation of society, with elaborate rules of sharing and etiquette evolving to take care of the elderly, orphans, and others without their own home and hearth.

These changes must have revolutionized protohuman intimacy. As our ancestors shifted from apelike sex lives to pair-bonding, proto-men's best strategy for passing on their genes shifted too, from fighting their way to the front of the line and flooding proto-women with semen toward skill at courting and providing. If

Homo ergaster

males still had quarter-pound testicles, they would have been as much of an expensive luxury as enormous intestines. Proto-men still faced sperm competition from seducers and rapists, and could not get away with gonads as tiny as alpha-male gorillas', but by modern times our testes had shrunk to just 1.5 ounces.

Along with huge scrotums, proto-men also lost a rather revolting feature of bonobo and chimpanzee penises: a little spur on the side that works to scoop any old deposits of semen out of a partner's vagina before inserting a new one. The fact that bonobos and chimpanzees both have these spurs strongly suggests that our last shared ancestor had them too and that protohumans lost their spurs because they no longer needed them. In their place, proto-men grew supersized phalluses. The average human erection is about six inches long, but chimpanzees and bonobos manage just three

inches, and gorillas a meager inch and a quarter. Proto-women returned the compliment by growing breasts that look like mountains compared with the molehills on other apes.

These anatomical peculiarities led Desmond Morris, a onetime keeper of primates at London Zoo, to conclude in his famous book

The Naked Ape

that humans are “the sexiest primate alive” (this was fifty years ago, before primatologists had discovered what bonobos get up to). Remarkably, zoologists cannot seem to agree on why human breasts and penises ballooned (“The inability of twentieth-century science to formulate an adequate Theory of Penis Length,” Jared Diamond dryly muses, is “a glaring failure”), but the obvious guess is that shifting from fighting for mates to courting them put a high priority on sending signals of sexual fitness, both to the opposite sex and to same-sex rivals. What better way to do that than by flaunting ostentatiously enormous organs?

By 1.3 million years ago, the point at which bonobos and chimpanzees began diverging, protohumans had already evolved very, very far from other apes. Just how that affected strategies of trauma, though, remains controversial, because we currently have nowhere near enough fossil skeletons to get a sense of how many protohumans were bludgeoned, stabbed, and otherwise done to death. To date, only one body dating back more than a million years bears traces of lethal trauma, and even that is not a certain case of deliberate killing. Only in the last half-million years, when skeletons become much more common, do we find unambiguously fatal wounds.

But given the similarities between the ways chimpanzees and modern humans fight, we can make some fairly secure speculations. In both populations, violence is overwhelmingly the preserve of young males, who are likely to be bigger, stronger, and angrier than females or old males. There is a saying that when you have a hammer, every problem looks like a nail, and to young male chimps and humans, wrapped in muscles and soaked in testosterone, many problems look like ones that force will solve. Primatologists tell us that males commit well over 90 percent of assaults among chimpanzees, and policemen tell us that the human statistics are very similar. Young males (human or chimpanzee) will fight over almost anything, with sex and prestige as the major flash points and material goods a rather distant third, and they are most likely to turn homicidal when they get together in gangs that outnumber their enemies.

Evolutionists cannot at this point prove that humans and chimpanzees inherited the practice of lethal male gang violence from proto-Pan, but it is certainly the most economical conclusion. If that is right, we should

probably also conclude that starting about 1.8 million years ago, pair-bonding made fighting less useful than courting as a mating strategy among

Homo ergaster

but did not reduce its value as a way to deal with rival communities of protohumans. Bonobos, by contrast, began evolving in an entirely different direction 1.3 million years ago, as female solidarity reduced the payoffs to male violence across the board. (Pair-bonding might actually have reduced the scope for bonobo-like group solidarity among protowomen.)

As archaeologists excavate more skeletons, the details will become clearer, but the one thing we can already be certain about is that the protohumans' new evolutionarily stable strategy was hugely successful.

Homo

went forth and multiplied as no ape had done before. Over the course of a thousand centuries, our ancestors spread across much of Africa, and a thousand centuries more of gradual extensions of their grazing ranges took them as far as what we now call England and Indonesia (the earliest skeleton with signs of violence in fact comes from Java). They moved into environments utterly different from the East African savanna, and, predictably, mutations flourished. Almost every year now brings an announcement that archaeologists or geneticists have discovered yet another new species of protohuman in Asia or Europe.