War: What is it good for? (56 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

The Politburo let this happen not because the apparatchiks had all been listening to “War” but because they knew force could not solve their problem. Invading West Germany or South Korea would not make the Soviet Empire as rich and productive as the American; it would just bring on Armageddon. For thirty years, the Soviets managed to paper over most of the cracks, convincing many of their subjects (and even some outsiders) that the empire was flourishing, but by the 1980s this was no longer possible.

By then, egg rationing and the other indignities of 1940s austerity were just distant memories for most western Europeans, but in eastern Europe it was all too easy to feel that they were on their way back. “It was a struggle to get basic things like washing powder,” a Polish nurse remembered. “I had to wash my hair with egg yolks because there was no shampoo ⦠If we didn't have information about life elsewhere, that would have been different. But we were conscious of the way [other] people lived.” And if anyone still had doubts that the Soviet bloc was losing the economic war, the meltdown of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor swept them away in 1986, flooding Ukraine with radiation and exposing the incompetence and dishonesty of the Soviet regime in a way that could not be covered up.

“We can't go on like this,” Mikhail Gorbachev had confessed to his wife in 1985, just hours before he was appointed Soviet premier. Desperate times call for desperate measures, and Gorbachev, recognizing that the Soviet Empire's will to resist was ebbing away, staked everything on one big bet. He would restart economic growth by promoting restructuring (perestroika) and transparency (glasnost) whileâat all costsâavoiding recourse to violence, which could only end badly.

Many Americans assumed that this must be another clever move in the game of death (so clever, in fact, that they could not quite figure out what the Soviets might be trying to do). “I was suspicious of Gorbachev's motives,” National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft later confessed. “My fear,” he explained, “was that Gorbachev could talk us into disarming without the Soviet Union having to do anything fundamental to its own military

structure and that, in a decade or so, we could face a more serious military threat than ever before.”

There were times when it looked as if Scowcroft might be right. In October 1986, Reagan and Gorbachev sat across a table in ReykjavÃk and actually started talking about banning all nuclear weapons. This threw American defense experts into a panic. The Soviets might be terrified of NATO's new, high-tech arsenal, but Americansâwho knew that few of these wonder weapons were yet in serviceâwere equally terrified that without nuclear deterrence their conventional forces in Europe would be hard-pressed to hold off the much larger Soviet armies. Gorbachev, however, was not trying to trick anyone, and it slowly became clear that he really was serious about playing the game without using force. No one knew what to make of it.

“Did we see what was coming when we took office [in January 1989]?” George Bush the Elder later asked, admitting, “No, we did not.” And if Bush

had

somehow seen how 1989 would turn out, and had claimed in his inauguration address that before his term ended he would oversee the collapse of the Soviet Empire and Russia's retreat to the borders Germany had imposed on it in 1918, everyone would have thought that this archrealist, former CIA director had gone completely mad. For more than forty years, the United States had been scheming, plotting, and killing, all to break the Soviets' will, but when the endgame finally arrived, it took everyone by surprise.

A few months after Bush's inauguration, an official committee in Hungary concluded that the country's 1956 rebellion against the Soviets had been a “popular uprising against an oligarchic system of power which had humiliated the nation.” In Stalin's day, such a report would have been equivalent to a collective suicide note. Even under Khrushchev or Brezhnev, the consequences could have been serious. But not only did Gorbachev not have anyone shot; he tacitly signaled agreement.

Encouraged, in June 1989 the Hungarians gave a retrospective public funeral to a former premier whom the Soviets

had

shot. Two hundred thousand mourners turned out, but still Moscow made no move. Without consulting anyone, the Hungarian prime minister announced that budgetary problems prevented him from renewing the barbed wire along the border with Austria, and since the old wire violated health and safety rules, it would have to be rolled up. A hole, hundreds of miles wide, was about to appear in the Iron Curtain. In a panic, East German communists asked the Kremlin to intervene, only to be told, “We can't do anything.”

Any amount of concession, Gorbachev reasoned, was better than risking the collapse of the whole Soviet system by using force. Not everyone agreed, and in December, Romania's thuggish dictator, Nicolae Ceausescu, had his troops shoot demonstrators. The country rose against him, the Soviets did nothing, and on Christmas Day he and his wife were themselves shot.

East German communists, scrambling and bungling almost as badly, lurched in the other direction and threw open the gates of the Berlin Wall. East Germans rushed west; West Germans strolled east; all kinds of people danced on top of the wall or took hammers to it; and nothing happened. “How could you shoot at Germans who walk across the border to meet other Germans on the other side?” Gorbachev asked the next day. “The policy had to change.”

The events in Romania suggested that Gorbachev was right, but by the summer of 1989 the Soviets probably had no winning moves left. Changing one policy just led to irresistible pressure on the next policy. Less than three months after the Berlin Wall came down, East Germany's prime minister told Gorbachev that the two Germanys wanted to merge into one. This could only happen, Gorbachev replied, if the unified Germany were demilitarized and neutral. A proposal was put to the Americans, but Bush refused to withdraw the quarter of a million American personnel in West Germany. Gorbachev pulled his 300,000 troops out of East Germany anyway, and the new, reunited Germany joined NATO.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is perhaps not surprising that once the Germans, Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Romanians, and Bulgarians had walked away from the Soviet Empire, the Estonians, Lithuanians, Latvians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Armenians, Georgians, Azeris, Chechens, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, and Mongolians would follow. What does still seem remarkable, though, is that the Russians themselves decided that they wanted nothing more to do with their own empire and announced their withdrawal from the Soviet system. On Christmas Day 1991, Gorbachev signed a decree formally dissolving the Soviet Union.

By playing the game without violence, Gorbachev got a bad payoff, but the only obvious alternativeâusing force to hold the eastern Europeans down and to resist any American effort to roll back the empireâwould have paid off much, much worse. Russia had been defeated, getting shoved unceremoniously out of the inner rim and even out of much of the heartland, but at least this had happened with barely a shot being fired. Five hundred million lives had been on the line during Petrov's moment of

truth in 1983, but when the end of the Cold War finally came, fewer than three hundred people actually died.

The United States had won the greatest and most unexpected triumph in the history of productive war (

Figure 6.10

). The world had a new glo-bocop.

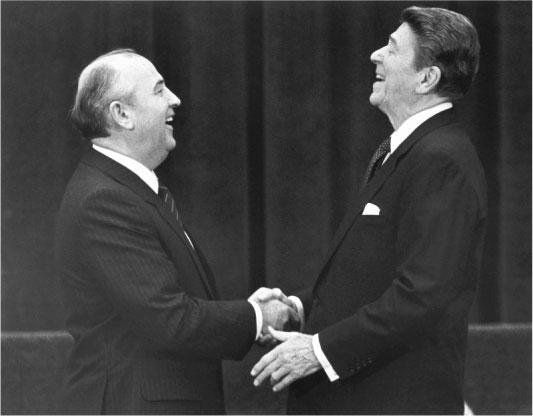

Figure 6.10. A lot to smile about: Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan bring down the curtain on the Cold War, and a billion people live to fight another day.

Footnotes

1

I say “according to the film” because, Richard Wrangham tells me, while Freddy, Scar, and their different behavior patterns are all real enough, the two chimps actually live on opposite sides of AfricaâFreddy in the Ivory Coast, and Scar in Uganda. The filmmakers took a little artistic license and stitched two separate tales together. The moral of the story, though, seems to survive this flexible approach to reality.

2

A hundred points strikes me as overoptimistic, given what we know about the scale of commerce in most periods of history, but since the numbers in these games are all made up, it hardly seems worth quibbling.

7

THE LAST BEST HOPE OF EARTH: AMERICAN EMPIRE, 1989â?

Can't Get There from Here

Monday, November 26, 2012, was a modern miracle. For an entire day (in fact, from 10:30 on Sunday night until 10:20 on Tuesday morning), not a single person was shot, stabbed, or otherwise done to death anywhere in New York City. There had been no such day since comprehensive data collection began in 1994, at which point the Big Apple averaged fourteen killings each day. In fact, we have to go back more than fifty years, to a time when records were spotty and the city had half a million fewer people, to find another day without violent death. All in all, in 2012 just one New Yorker in twenty thousand died violentlyâprobably an all-time low.

New York is not, of course, the only place in America. In Chicago, murders rose by one-sixth in 2012, while San Bernardino, Californiaâwhere half the homeowners owe more than their houses are worth and the city government has gone bankruptâsaw killings jump 50 percent (“Lock your doors and load your guns,” the city attorney advised). And as 2012 drew to a close, a psychopath in Newtown, Connecticut, gunned down twenty schoolchildren, six staff members, his own mother, and then himself. Yet New York was more typical than Newtown: despite the nightmarish exceptions, the nation's murder rate fell in 2012.

In fact, New York is fairly typical not just of the United States but also of much of the world. Homicide is in general retreat. Roughly 1 human in every 13,000 was murdered in 2004; by 2010, the figure had fallen to just over 1 in every 14,500. Deaths in war went the same way. Interstate warsâ

typically the biggest and bloodiest conflictsâalmost disappeared. Civil wars in the wake of state failures continue (in 2012, civil war killed about 1 Syrian in every 400), but the statistics suggest that these conflicts are becoming rarer too.

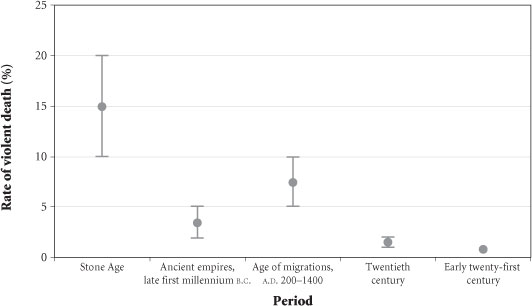

Averaged across the planet, violence killed about 1 person in every 4,375 in 2012, implying that just 0.7 percent of the people alive today will die violently, as against 1â2 percent of the people who lived in the twentieth century, 2â5 percent in the ancient empires, 5â10 percent in Eurasia in the age of steppe migrations, and a terrifying 10â20 percent in the Stone Age (

Figure 7.1

). The world is finally getting to Denmark, and Denmark itselfâwhere just 1 person per 111,000 was murdered in 2009, representing a lifetime risk of violent death of just 0.027 percentâgets more Danish every day. Most wonderful of all, for every twenty nuclear warheads in the world in 1986âwhen Bruce Springsteen rerecorded “War”âthere is now only one. Fifty years ago, Strategic Air Command (charged with delivering nuclear weapons) was at the cutting edge of the U.S. Air Force; nowadays, most air force officers consider going into the nuclear branch career suicide.

Figure 7.1. Almost there: rates of violent death, 10,000

B.C.âA.D.

2013

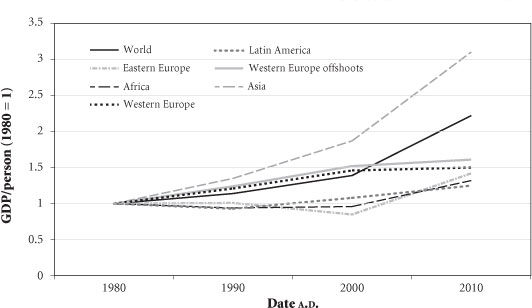

Nor is that the end of the good news. As has happened so often across the last few thousand years, falling rates of violence have gone hand in hand with rising prosperity. When the United States took over as undisputed globocop in 1989, the average human being generated just over $5,000

of wealth.

1

By 2011, the most recent year with complete data, that had doubled. Asia had benefited most, with coastal China, parts of Southeast Asia, and a few regions in India going through their own industrial revolutions. These fueled the greatest migration of peasants into cities in history, lifting more than two billion people out of absolute poverty (defined by the World Bank as surviving on less than $1 per day). Latin America, Africa, and eastern Europe initially went backward, thanks to debt crises, the AIDS epidemic, and postcommunist collapse, respectively, but all have gained ground since 2000 (

Figure 7.2

).

Figure 7.2. The rich get richer, and the poor get richer faster: the speed at which wealth grew in different parts of the world between 1980 and 2010. Globally, the average person was 2.2 times richer in 2010 than in 1980, but the average Asian was three times richer. Africans and Latin Americans got poorer in the 1980s and eastern Europeans in the 1990s, but all have gained on northwestern Europeans and their settler colonies (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) since 2000.

Figures 7.1

and

7.2

are remarkable graphs, showing that the world is getting not just safer and richer but alsoâas inequalities between the continents declineâfairer. Even more remarkable, however, is the explanation for all this good news, argued throughout this book: that productive war has made the planet a better place. This is a paradoxical, counterintuitive, and frankly disturbing notion (and, as I mentioned in the introduction, not one that crossed my mind before I started studying the long-term history of war). But the evidence of archaeology, anthropology, history, and evolutionary biology seems conclusive.

Violence evolved 400 million years ago as a way to win arguments (initially, between proto-sharks that wanted to eat other fish and other fish that did not want to be eaten). It has been a hugely successful adaptation, and almost all animals now use it. Some have even evolved to use violence collectively, and when territory is involved, this violence can be lethal. War has come into the world.

Human history is one of the shorter twigs on the evolutionary tree, but it is by far the most unusual. We alone can evolve culturally as well as genetically, responding to changes in the payoffs from the game of death by altering our behavior rather than waiting thousands of generations for natural selection to change us. Because of this, since the end of the last ice age we have found ways to use violence thatâparadoxicallyâhave lowered the payoffs from using further violence.

When the world warmed up after 10,000

B.C.

, animals and plants of all kinds reacted by reproducing. For most species, hard times returned when hungry mouths outran food supplies, but in the lucky latitudes humans solved this problem by evolving culturally and becoming farmers. Farming had its costs, but it also supported many more people, and the resulting

crowding created caging. For chimpanzees and probably for ice-age humans too, territoriality meant that the highest payoffs in the game of death came from killing competing groups, but caging meant that incorporating defeated enemies into larger societies paid off better still. “Incorporation” is a bland word for a process that included so much plunder, rape, enslavement, and displacement, but because competition rewarded conquerors who turned themselves into stationary bandits, the long-term result of all this violence was pacification and rising prosperity.

By 3500

B.C.

, stationary bandits were evolving into genuine Leviathans, able to raise taxes and punish recalcitrant subjects. The process began in what we now call the Middle East because that was also where farming had begun, and it was therefore the place where caging and competition had gone furthest; but over the next few thousand years most of the lucky latitudes moved the same way.

Each region in the Old World's lucky latitudes went through a similar sequence of revolutions in military affairs (although, for reasons we saw in

Chapter 3

, and above all the absence of horses, the sequence in the New

World differed somewhat). First came fortifications, as an answer to endemic raiding; attackers responded by learning how to besiege walls they could not climb. Next, in Eurasia, came bronze, for offensive weapons and defensive armor. Then there was discipline, to persuade wild young men to attack despite the danger and to stand their ground against murderous enemies. By 1900

B.C.

, herders on Eurasia's steppes learned to harness horses to chariots, bringing speed and fluidity to battlefields. By 1200

B.C.

, warriors around the Mediterranean found ways to fight back, but in the first millennium

B.C.

the initiative shifted toward masses of iron-armed infantry, which conquered huge empires all across Eurasia's lucky latitudes.

Each revolution was a race between offense and defense, but, as I have insisted throughout this book, war was never a case of what evolutionists call the Red Queen Effect. The race did not leave everyone in the same place, because it transformed the societies that ran it. Every revolution required Leviathans to get stronger, and stronger Leviathans drove down rates of violent death still further.

Nor do the facts fit comfortably with the theory of a unique Western way of war, invented by the Greeks in ancient times and raising European fighters above everyone else in the world. In reality, people all across the lucky latitudes invented a single productive way of war, and what it produced was stronger Leviathans, safety, and wealth. In the first millennium

B.C.

, people got to Chang'an, Pataliputra, and Teotihuacán as well as Rome.

Another theme in this book, though, is that everything in war is paradoxical. By the end of the first millennium

B.C.

, Eurasia's productive wars were reaching what Clausewitz called a culminating point, at which behavior that previously produced success started delivering disaster. The ancient empires' expansion increasingly entangled them with the steppes. Here, highly mobile horsemen could cover vast distances and strike into the empires almost at will, but the great infantry armies that had created the empires struggled to survive at all on the arid grasslands. From China to Europe, cavalry came to dominate the battlefield, and for more than a thousand yearsâfrom roughly

A.D.

200 through 1400âthe lucky latitudes and steppes were locked in a terrible cycle of productive and counterproductive wars. For every productive war that produced bigger, safer, and richer societies, a counterproductive war broke them down again. Leviathans lost their teeth, rates of violent death rose, and prosperity fell.

One day, not too far away, physical anthropologists will have studied

enough skeletons to put precise numbers on these rates, but for the time being, we have to rely on the impressionistic evidence that I reviewed in

Chapters 1

â

3

. For prehistory, we can combine analogies from twentieth-century Stone Age societies with the small but growing body of skeletal evidence, but for the ancient empires and the age of steppe migrations we have to rely largely on the societies' own literary accounts. I argued in

Chapters 1

and

2

that these writings make it almost certain that the ancient empires reduced rates of violent death and in

Chapter 3

that rates rose again after about

A.D.

200, but at the moment there is frankly no way to know precisely

how much

they rose and fell.

My own estimatesâthat the risk of violent death was in the 2â5 percent range in the ancient empires, rising to 5â10 percent in the times of feudal anarchyâwill doubtless be proved wrong as evidence accumulates, but that, it seems to me, is how scholarship is supposed to work. One researcher makes conjectures; another comes along and refutes them, putting better conjectures in their place. But if nothing else, I hope this first stab at putting actual numbers on the table will provoke others to disprove them by collecting better data and devising better methods that reveal where I went wrong.