War: What is it good for? (54 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Whatever the chain of cause and effect, it is a depressing coincidence that as our kind of humans spread, every other kind fled. By twenty-five thousand years ago, Neanderthals had retreated to a few inaccessible caves at Gibraltar and in the Caucasus Mountains, and by twenty thousand years ago they were gone altogether. Other kinds of protohumans hung on, on isolated islands, until 18,000

B.C.

, and people claim to see Yetis even today, but all the hard evidence says that we are alone and have been since the coldest point of the last ice age, two hundred centuries ago.

This was just the beginning of the ways culture would transform the planet. I spent a page or two in

Chapter 2

talking about how, when the most recent ice age ended around 9600

B.C.

, plants multiplied madly and animalsâincluding humansâate them and multiplied madly too. For all animals except humans, these good times lasted only a few generations, until their own numbers outran their increased food supply and hunger returned. The humans in the lucky latitudes, though, were able to respond by evolving culturally, domesticating plants and animals to increase their food supply.

When I talked about the beginnings of agriculture in

Chapter 2

, I called it one of the two or three great turning points in human history, in part because the new and crowded farming landscapes made it harder for losers in the game of death to run away. This turned territoriality into caging, but whereas territory gave ants and apes reasons to fight to the death, caging had more complicated effects on us. In fact, it created the new evolutionarily stable strategy that I have been calling productive war. This rewarded people who kept killing until their rivals lost their will to resist, but beyond that point it rewarded people who accepted their defeated enemies' signals of submission rather than slaughtering them. Cultural evolution turned killers into conquerors, ruling over larger, safer, and richer societies.

Chimpanzees do incorporate some defeated enemies into their own communities, as the Kasekela chimps did with the last surviving Kahaman females at the end of the Gombe War in 1977. But chimpanzees lack the flexible brainpower for cumulative cultural evolution. There are no simian cities or ant empires, because communities that grow too large break apart, rather like the carbon blobs in the early earth's oceans. This, in fact, was how the Kasekela and Kahama chimpanzee bands originally emerged. When Jane Goodall set up her research station at Gombe in 1960, there

was only one community of chimps, but this grew and then split in two in the early 1970s.

Humans, by contrast, can organize themselves to live in larger and more complex groups without having to evolve biologically into a whole new kind of animal. In the increasingly competitive caged world of the post-Ice Age lucky latitudes, bigger communities could generally outcompete smaller ones, but holding big groups together required leaders to foster internal cooperation so that the group could compete better against outsiders.

So it was that Leviathans became part of the human evolutionarily stable strategy. Once again, we can see a pale shadow of human behavior among chimpanzees, who fight less often when they live in communities with a well-established alpha male than in bands where the hierarchy is unsettled. And like human leaders who turn into stationary bandits as they pursue their self-interest, really entrenched alpha males can be surprisingly impartial and even altruistic toward the weak. The extreme case may be Freddy, a supremely secure alpha-male chimp in the Taï Forest in West Africa. The wildly popular Disney nature documentary

Chimpanzee

shows Freddy feeding and caring for an orphaned baby chimp named Oscar, even though this cost Freddy time that he would ordinarily have spent patrolling the borders with other adult males. According to the film, though, all ended well, with Freddy's troop seeing off a raid by the neighboring community, whose chiefâthe villainous Scarâhad failed to prevent rifts from growing among his followers.

1

Like so many great leadersâmost famously, perhaps, Abraham LincolnâFreddy set an example of cooperation that perhaps helped his team of rivals work together well. Yet Freddy will not be founding a dynasty that steadily drives down rates of lethal violence in the Taï Forest. To do that, he and his troop would need to evolve biologically into animals that, like humans, can evolve culturally. Alpha-male chimps cannot reorganize their societies to build on their predecessors' accomplishments any more than they can foster revolutions in military affairs. Only we can do these things.

And these things, as we saw in

Chapters 1

â

5

, are precisely what we have done in the last ten thousand years. We have made bigger societies that constantly revolutionize their military affairs. Fortifications, metal arms and armor, discipline, chariots, massed iron-armed infantry, cavalry, guns, battleships, tanks, aircraft, nuclear weaponsâthe list goes on and on, with each advance allowing us to wage ever-fiercer wars; but to compete in these conflicts, our bigger societies have also had to find ways to get their members to cooperate better, which has pushed them toward stationary bandits, internal peace, and prosperity. In this peculiar, paradoxical way, war has made the world safer and richer.

The Pacifist's Dilemma

In

The Better Angels of Our Nature,

perhaps the best book on the modern decline of violence since Norbert Elias's

Civilizing Process,

the psychologist Steven Pinker illustrates his arguments about the increasing peacefulness of Europe and North America since

A.D.

1500 with a game that he calls “the Pacifist's Dilemma.” The basic format is much like the hawk-and-dove and sheep-and-goat games that I played earlier in this chapter. Pinker assumes that anytime there is a dispute to be resolved, the payoff of cooperating is +5 points for each player. The payoff of attacking an unsuspecting player and just taking what you want is +10 points, while the cost of suffering such an attack is a disproportionate â100 points. (If you have ever been mugged, that will make sense.) As we might expect, the fear of losing 100 points is enough to make everyone trigger-happy, even though the payoff when both players attack is â50 points all around (both players get hurt, and neither gets what he or perhaps she wants). Everyone would like the +5 payoff from cooperating but settles for the â50 of fighting to avoid getting the â100 of being mugged.

And yet, over the past few centuries, fighting has been declining, and the world has been drifting toward +5. As Pinker points out, the logic of the game of death means the only possible explanation is that the payoffs have changed over time. Either the rewards of peace or the costs of fighting (or both) have risen so much that the number of situations in which force pays off has shrunk, and we have responded by using force less and less often.

The changes those of us now in middle age have seen during our own lifetimes are frankly quite remarkable. A few years ago, while I was directing an archaeological excavation in Sicily, the topic of fighting came up one

evening over dinner. One of the students on the digâa big, strapping lad in his early twentiesâcommented that he couldn't imagine what it would feel like to hit someone. I thought he was joking, until it became clear that almost no one at the table had ever raised a hand in anger. For a moment, I felt as if I had stepped into an episode of

The Twilight Zone

. I had hardly been a wild child, but there was no way I could have gotten through high school back in the 1970s without throwing the occasional punch. Admittedly, students from Stanford University may be near one extreme of the nonviolent spectrum (psychologists call such people WEIRDâ“Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic”), but even so they belong to a broader trend. We are living in a kinder, gentler age.

Pinker suggests that five factors have changed the payoffs from violence, making force less attractive. First, he says, comes our old friend Leviathan. Governments have become stationary bandits, penalizing aggressors. In his Pacifist's Dilemma game, even quite a small penalty of â15 points would push the payoff from winning a fight down from +10 to â5 points, which would be less than the +5 average from being peaceful. This would soon have Leviathan's subjects burying the hatchet.

But government, Pinker argues, was just the first step. Commerce has also increased the payoffs from peace. If gains from trade were to add 100 points to each player's payoff whenever they both chose cooperation over fighting,

2

Pinker observes, the resulting score of +105 points would dwarf the +10 that anyone would score by winning a war (let alone the â50 he would suffer from a war that dragged on without victory).

And then, Pinker says, there is feminization. In every documented human society, males are responsible for nearly all the violent crime and war-making. Throughout history, menâand male valuesâhave dominated, but in the last few centuries, beginning in Europe and North America and then spreading around the world, women have been increasingly empowered. We have not gone as far as bonobos, among whom females keep aggressive males in their place, but, Pinker suggests, feminism has reduced the payoff from violence by making machismo look ridiculous rather than glorious. If, he speculates, 80 percent of the payoff from successful violence is psychological, then the growing importance of feminine values would drive the gains from victories down from +10 to +2 points. This is

well under the +5 points that everyone gets for being peaceful, and would quickly turn pacifism into the new evolutionarily stable strategy.

Nor is that all. Since the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, Pinker goes on to suggest, empathy has become increasingly important. “I feel your pain” is not just New Age nonsense; seeing other people as fellow humans has raised not only the psychological payoffs from helping them but also the costs of hurting them. If choosing peaceful cooperation gives each player just an extra 5 points' worth of pleasure, it would raise both sides' payoff from working together to +10 points, and then any reduction at all for guilt from causing pain would drive the payoff of aggression down below +10 points. Peace, love, and understanding would win the day.

Finally, Pinker suggests, science and reason have also changed payoffs. Since the seventeenth-century scientific revolution, we have learned to view the world objectively. We understand how the universe began, that the earth goes around the sun, and how life evolved. We have found the Higgs boson and even invented game theory. Knowing that cooperation is more rational than using force must raise the psychological payoff from the former while reducing the payoff from the latter.

It is hard to disagree with any of Pinker's points, but I think we can actually go further. In the introduction to this book, I suggested that long-term global history is one of our most powerful tools for making sense of the world, and I now want to suggest that by limiting his focus to western Europe and North America in the last five hundred years, Pinker actually saw only part of the picture. If we instead look at the entire planet across the last hundred thousand years, we find that the story is simultaneously more complicated and much simpler than Pinker suggests.

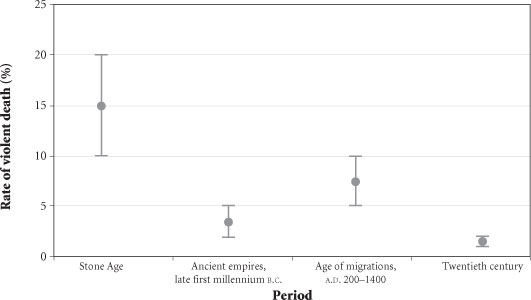

What makes the story more complicated is that the Euro-American decline in violence in the last half millennium was not a onetime event. In

Chapters 1

and

2

, we saw that rates of violent death also fell in the age of ancient empires, tumbling by the end of the first millennium

B.C.

to perhaps just one-quarter of what they had been ten thousand years earlier. Between

A.D.

200 and 1400, rates of violence then rose again in Eurasia's lucky latitudes, where the bulk of the world's population lived (

Chapter 3

), before a second great pacificationâthe one Pinker focuses onâbegan (

Chapters 4

and

5

). Well before 1900, the risk of violent death had fallen even lower than in the days of the ancient empires, and since then it has just carried on sliding (

Figure 6.9

).

Figure 6.9. The big picture: rates of violent death, 10,000

B.C.âA.D.

2000

What makes the story simpler than Pinker's, however, is that when we compare the ancient and the modern periods of declining violence and

contrast them with the intervening medieval period of rising violence, we find that we only need one factor, not five, to explain why violence declined. That factor, you will probably not be surprised to hear at this point in the book, is productive war.

Pinker recognizes that “a state that uses a monopoly on force to protect its citizens from one another may be the most consistent violence-reducer,” but the reality seems simpler to me. For ten thousand years, productive war has always been the prime mover in reducing violence, creating bigger societies ruled by Leviathans, which, to survive in competition with other Leviathans, have to turn into stationary bandits that punish unauthorized violence. Pinker's other four factorsâcommerce, feminization, empathy, and reasonâare always consequences of the peace brought by productive war, not independent causes in their own right.