Warblegrub and the Forbidden Planet (14 page)

*

Alex and the birdpeople gathered round the fire as Shmi produced wooden bowls and spoons from her bag and served them a delicious meal. The extraordinary flavours belied the meagre ingredients of weeds and fungi, and quite how the cooking pot, ladle and other kitchen tools had been carried in her little shoulder bag was yet another mystery. But Alex had given up questioning such oddities.

While they ate, the sun rose over a city on the edge of a shining sea, now all but consumed by the forest. As Shmi told them the story of that once proud capital of empires, Alex imagined the golden domes gleaming again and the slender towers casting long shadows over teeming, sprawling suburbs. Shmi pointed to a waterway winding through the city like a glorious ribbon of gold.

“That narrow strait is the boundary between two great continents and a channel between two seas, and the reason why this fair city was one of the most famous and fought over in mankind’s short history.”

In her mind’s eye, Alex saw the fleets of ships that had passed this way down the millennia: banks of long oars, blades flashing in the sunlight; booming sails like angel’s wings, tall-funnelled steamships belching smoke, huge cargo ships laden to the gunwales and nuclear warships, sleek and deadly. And while their vessels and the world around them changed, the mariners’ purpose remained constant – plying trade between far-flung lands.

“And over there,” said Shmi, pointing into the hazy distance, “not far away, was another famous city called Troy. In ancient times the Trojans controlled these prosperous waters but, as always with mankind, greed and jealousy ensued and brought about one of your first great and pointless wars. Troy was utterly destroyed, of course.” She fell silent, remembering the sack of the city and the suffering of defenceless women and children.

“I was told the Trojans kidnapped a princess of the Greeks,” Alex interrupted, “and it was for love that the war began.”

“Love!”

Shmi snorted. “When do you humans fight for anything other than wealth and land?”

Saddened by the tale, Shmi had nothing more to say. Perching in the branches of a tree just overhead, the birdpeople began to sing softly and Alex’s mind returned to the suspicion that had been nagging her since they had parted from Warblegrub.

“Am I some kind of sacrifice for this…? What’s her name?”

“Kali.”

“…this Kali?”

“Not at all!” replied Shmi brightly. “You’ll be perfectly safe, dear.”

“But she’s Fardelbear’s

wife!

”

Shmi smiled fondly. “She’s a sweetie once you get to know her.”

“But why am I here?”

“Many holy men and philosophers have asked that same question….”

“I mean – why did you bring me with you?”

“I’ll explain later,” Shmi promised and she too began to sing.

The song was a melancholy one, and in a language unknown to Alex. As she looked out over the domes and towers, she guessed it had been sung by the people who had once lived here.

Leaving the city behind, they flew over arid highlands and deep fertile valleys, crossed a great desert, then a land of broad rivers and long-dead cities. Alex’s wonder grew with every stage of their journey but she was truly astonished when they entered an enormous valley climbing hundreds of kilometres into a vast range of snow-capped mountains.

“They’re incredible!” she marvelled. “I’ve never seen anything like them.”

Shmi looked over at her, suddenly curious. “I believe your own ancestors came from this part of the world,” she said.

Alex looked pleased and surprised.

Shmi frowned. “And yet your name is Alex – hardly typical for your people!”

“It came to my mother in a dream,” said Alex. “She thought it was probably the name of a great hero, Alexander the Great, and she foresaw what a tomboy I’d be.”

Shmi shook her head. “Not he.”

“Then who?”

“It’s meaning will come clear in time,” she said with an enigmatic smile.

High in the mountains, the elements quickly turned against them. Clouds filled the upper reaches of the valley, a gale blew up and the rain came lashing down. Shmi and Alex left the birdpeople to dry their wings in the shelter of a thick pine forest.

“Follow as soon as you can,” Shmi told them, “or wait for us here if the storm doesn’t pass.”

Leaving them huddled round a small fire, they began to climb. With Shmi holding her hand, Alex was able to move effortlessly and at an incredible speed. They traversed a narrow ravine and scaled a sheer cliff with ease, and soon emerged onto a high plateau above the storm. The air was clear and cold and Alex wondered how she could even breathe at such an altitude until she remembered their flight through space. Everything she thought she had known about the nature of the Universe had been turned on its head since her arrival on Earth and she wondered whether anything would ever surprise her again. But of all the astonishing revelations she had witnessed so far, nothing had quite prepared her for what she was about to see.

As they skirted the edge of a pine-shrouded valley, through which a river cascaded over dozens of waterfalls, Shmi stopped to listen. At first Alex could only hear birdsong and the tumbling waters, though Shmi could clearly hear more. Delight lit up her face and, without a thought for the steepness of the slope or an explanation for her companion, she ran off down the hillside and vanished into the trees. Listening intently, Alex heard voices that sounded human and scrambled down the steep slope after Shmi, slipping and sliding, battered by whipping branches.

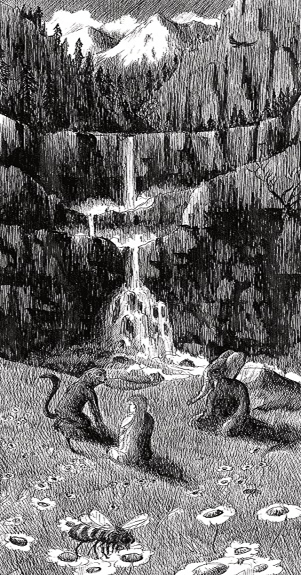

At the bottom of the slope, the trees gave way to a sunlit, grassy meadow where tiny alpine flowers grew thick as stars and a slender waterfall filled a deep pool. Shmi was sitting there, beside the pool, talking to an elephant and a large silver-grey monkey.

Chapter Fifteen

Seagulls bobbed on a gentle wave as it rolled ashore and broke leisurely over the rocks. The wave rolled back, dragging pebbles clattering down the beach, and the next advanced. Hour after hour, the waves rolled ashore, the seagulls bobbed and the morning passed uneventfully. Then, shortly before midday, a rush of bubbles broke the surface and the gulls rose screeching into the air. One after another, small black humps appeared just offshore and divers rose from the waves.

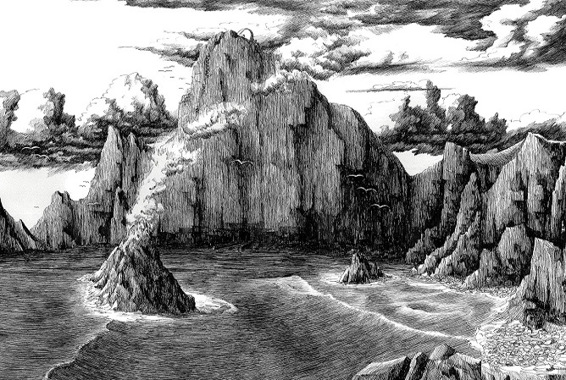

Staggering ashore at the southernmost tip of the crescent-shaped island, most of the company pulled off their masks and collapsed, sprawled over the nearest rock; but 395 and the Colonel surveyed their new surroundings, taking in the great sweeping curve of the bay, the young volcano belching smoke, the massive cliff wall, the deep space transmitter a mere dot on top.

“Almost a thousand metres,” observed 395, as the height registered on his visor.

“What about that?” the Colonel asked, indicating the young volcano.

“Smoke’s thicker than it was on the satellite image,” 395 noted.

“D’you think it’s going to erupt?”

“Can’t be sure, but I haven’t felt any earth tremors so I guess we’re safe for now. Let’s not loiter though!”

The Colonel and Sergeant 207 got most of the company on their feet but Privates 856, 1642 and Sarah remained seated. While the others ditched their diving gear and gathered their packs, the Colonel confronted the stragglers.

“Move!” he ordered, drawing a revolver.

1642 and 856 rose as quickly as they were able, saluted and joined the column, but Sarah remained seated, her back against a rock.

“We’re all tired,

soldier!

”

“I’m not tired.”

“Then it’s mutiny?”

She shrugged. “We shouldn’t be here, Colonel.”

He made no threat and gave no warning; a shot rang out and the others saw Sarah topple over and lie still. Corporal 236 reached for her sidearm but felt the barrel of a gun in her back.

“Make my day!” hissed Sergeant 207.

“Anyone else refusing to do their duty will get the same,” the Colonel warned.

Ordered to take the lead, at first 395 was unable to take his eyes off the body of his friend.

“Move it, S.O.!” barked 207.

Tearing himself away, he obeyed and, under the new Sergeant’s glare and the threat of his Redeemer, the rest fell in line. They followed the long curving shoreline towards the base of the cliff, where the entrance of a tunnel was just visible in the shadows. More deeply shaken than ever, their reserves of energy drained and their rations almost exhausted, they stumbled along the shore like raw recruits, as frightened of the Colonel as they had been of Fardelbear. Reluctantly, he permitted another rest in the warm sunlight before the shadow of the cliff fell over them, and as they nibbled the contents of their last ration packs, they craned their necks and looked up at the mountaintop, wondering whether they were truly in reach of their goal.

“So it’s the remains of a volcano?” said Private 2116, squatting next to 395.

395 nodded.

“Must’ve been one hell of an eruption!”

395 nodded again.

“And the transmitter’s up there?”

He received a grunt in reply.

“How do we get up there?”

“Over there,” 395 replied curtly, pointing in the direction of the tunnel mouth. Then, realising the young man was anxious and craved conversation, he tried to be more comradely. “According to the database this was a major deep space communications centre,” he explained. “There’s a network of tunnels and old lava passages inside the mountain.” He pointed to a peculiar little feature two-thirds of the way up the cliff wall. “See that?”

Magnified through his visor, Private 2116 saw a tiny door in the cliff and a platform at the bottom of a series of rusting stairs and walkways that climbed towards the summit. “Do you think they’ll take our weight?”

“We’ll find out soon enough.”

2116’s laughter was shrill and the silence returned with a vengeance. Feeling lonely, 395 looked round for Peter but he was nowhere to be seen. Alerted at last to his disappearance, most of the company presumed he had been killed in the undersea trench but 395 was certain he had been with them in the sunken city.

Even more disheartened by the loss of Private 585, the company crossed the beach and came to a boulder-choked canal. Following the towpath, they entered a short tunnel and found the entrance to the base. The bombproof doors were unlocked and, with an effort, they pulled them wide enough apart to reveal a huge chamber stretching away into darkness, its flat ceiling supported by a forest of pillars. There were piles of crates, boxes and drums, and forklift trucks lay abandoned in the aisles they created. Near the door there was a row of jeeps and several large amphibious vehicles, and ahead was a particularly thick pillar housing lifts and stairs.

Private 312 and Corporal 236 led the way; Sergeant 207, Science Officer 395 and the Colonel were next, then Privates 856 and 1642, with 941 and 2116 bringing up the rear; all that remained of the ninety-two men and women who had landed a few days before.

*

The elephant and monkey were sitting cross-legged among the flowers, conversing fluently with Shmi. As a child, Alex had been fascinated by the idea of creatures such as these and, having read a good deal about the natural history of Earth, she was certain they could not speak – certainly not as well as these! She was seriously concerned for her sanity but when she emerged into the sunlight, the animals were even more startled than she.