Water for Elephants (24 page)

Read Water for Elephants Online

Authors: Sara Gruen

I blink rapidly, trying to get my bearings—that skinny nurse with the horse face has dropped a tray of food at the end of the hall, and it’s woken me up. I wasn’t aware of dozing, but that’s how it goes these days. I seem to slip in and out of time and space. Either I’m finally going senile, or else it’s my mind’s way of coping with being entirely unchallenged in the present.

The nurse crouches down, collecting the spilled food. I don’t like her—she’s the one who’s always trying to keep me from walking. I think I’m just too wobbly for her nerves, because even Dr. Rashid admits that walking is good for me as long as I don’t overdo it or get stranded.

I’m parked in the hallway just outside my door, but it’s still several hours before my family comes and I think I’d like to look out the window.

I could just call the nurse. But what fun would that be?

I shift my bottom to the edge of my wheelchair, and reach for my walker.

One, two, three—

Her pale face thrusts itself in front of mine. “Can I help you, Mr. Jankowski?”

Heh. That was almost too easy.

“Why, I’m just going to look out the window for a while,” I say, feigning surprise.

“Why don’t you sit tight and let me take you?” she says, planting both hands firmly on the arms of my chair.

“Oh, well then. Yes, that’s very kind of you,” I say. I lean back in my seat, lift my feet onto the footrests, and fold my hands in my lap.

The nurse looks puzzled. Dear Lord, that’s an impressive overbite. She

straightens up and waits, I guess to see if I’m going to make a run for it. I smile pleasantly and train my gaze on the window at the end of the hall. Finally, she goes behind me and takes the handles of my wheelchair.

“Well, I must say, Mr. Jankowski, I’m a little surprised. You’re normally . . . uh . . . rather

adamant

about walking.”

“Oh, I could have made it. I’m only letting you push me because there aren’t any chairs by the window. Why is that, anyway?”

“Because there’s nothing to see, Mr. Jankowski.”

“There’s a circus to see.”

“Well, this weekend, maybe. But normally there’s just a parking lot.”

“What if I want to look at a parking lot?”

“Then you shall, Mr. Jankowski,” she says, pushing me up to the window.

My brow furrows. She was supposed to argue with me. Why didn’t she argue with me? Oh, but I know why. She thinks I’m just an addled old man. Don’t upset the residents, oh no—especially not that old Jankowski fellow. He’ll fling pockmarked Jell-O at you and then call it an accident.

She starts to walk away.

“Hey!” I call after her. “I haven’t got my walker!”

“Just call me when you’re ready,” she says. “I’ll come get you.”

“No, I want my walker! I always have my walker. Get me my walker.”

“Mr. Jankowski—” says the girl. She folds her arms and sighs deeply.

Rosemary appears from a side hall like an angel from heaven.

“Is there a problem?” she says, looking from me to the horse-faced girl and then back again.

“I want my walker and she won’t get it,” I say.

“I didn’t say I wouldn’t. All I said was—”

Rosemary holds up a hand. “Mr. Jankowski likes to have his walker beside him. He always does. If he asked for it, please bring it.”

“But—”

“But nothing. Get his walker.”

Outrage flashes across the horse girl’s face, replaced almost instantly by hostile resignation. She throws a murderous glance my direction and goes back for my walker. She holds it conspicuously in front of her, storming down the hall. When she reaches me, she slams it in front of me. Which

would be more impressive if it didn’t have rubber leg caps, making it land with a squeak rather than a bang.

I smirk. I can’t help it.

She stands there, arms akimbo, staring at me. Waiting for a thank you, no doubt. I turn my head slowly, chin raised like an Egyptian pharaoh, training my gaze on the magenta and white striped big top.

I find the stripes jarring—in my day, only the concession stands were striped. The big top was plain white, or at least started out that way. By the end of the season it may have been streaked with mud and grass, but it was never striped. And that’s not the only difference between this show and the shows from my past—this one doesn’t even have a midway, just a big top with a ticket gate at the door and concession and souvenir stand beside it. It looks like they still sell the same old fare—popcorn, candy, and balloons—but the children also carry flashing swords, and other moving, blinking toys I can’t make out at this distance. Bet their parents paid an arm and a leg for them, too. Some things never change. Rubes are still rubes, and you can still tell the performers from the workers.

“M

R

. J

ANKOWSKI

?”

Rosemary is leaning over me, seeking my eyes with hers.

“Eh?”

“Are you ready for lunch, Mr. Jankowski?” she says.

“It can’t be lunchtime. I only just got here.”

She looks at her watch—a real one, with arms. Those digital ones came and went, thank God. When will people learn that just because you can make something doesn’t mean you should?

“It’s three minutes to twelve,” she says.

“Oh. All right then. What day is it, anyway?”

“Why, it’s Sunday, Mr. Jankowski. The Lord’s Day. The day your people come.”

“I know that. I meant what’s for lunch?”

“Nothing you’ll like, I’m sure,” she says.

I raise my head, prepared to be angry.

“Oh, come now, Mr. Jankowski,” she says, laughing. “I was only joking.”

“I know that,” I say. “What, now I have no sense of humor?”

But I’m grumpy, because maybe I don’t. I don’t know anymore. I’m so used to being scolded and herded and managed and handled that I’m no longer sure how to react when someone treats me like a real person.

R

OSEMARY TRIES TO

steer me toward my usual table, but I’m having none of that. Not with Old Fart McGuinty there. He’s wearing his clown hat again—must have asked the nurses to put it on him again first thing this morning, the damned fool, or maybe he slept in it—and he’s still got helium balloons tied to the back of his chair. They’re not really floating anymore, though. They’re starting to pucker, hovering above limp lengths of string.

When Rosemary turns my chair toward him I bark, “Oh no you don’t. There! Over there!” I point at an empty table in the corner. It’s the one farthest from my usual table. I just hope it’s out of earshot.

“Oh, come now, Mr. Jankowski,” Rosemary says. She stops my chair and comes around to face me. “You can’t keep this up forever.”

“I don’t see why not. Forever might be next week for me.”

She puts her hands on her hips. “Do you even remember why you’re so angry?”

“Yes, I do. Because he’s lying.”

“Are you talking about the elephants again?”

I purse my lips by way of an answer.

“He doesn’t see it that way, you know.”

“That’s cockamamie. When you’re lying, you’re lying.”

“He’s an old man,” she says.

“He’s ten years younger than me,” I say, straightening up indignantly.

“Oh, Mr. Jankowski,” Rosemary says. She sighs and gazes toward heaven as though asking for help. Then she crouches in front of my chair and places her hand on mine. “I thought you and I had an understanding.”

I frown. This is not part of the usual nurse/Jacob repertoire.

“He may be wrong in the details, but he’s not lying,” she says. “He really

believes

that he carried water for the elephants. He does.”

I don’t answer.

“Sometimes when you get older—and I’m not talking about you, I’m

talking generally, because everyone ages differently—things you think on and wish on start to seem real. And then you believe them, and before you know it they’re a part of your history, and if someone challenges you on them and says they’re not true—why, then you get offended. Because you don’t remember the first part. All you know is that you’ve been called a liar. So even if you’re right about the technical details, can you understand why Mr. McGuinty might be upset?”

I scowl into my lap.

“Mr. Jankowski?” she continues softly. “Let me take you to the table with your friends. Go on, now. As a favor to me.”

Well, isn’t that just dandy. The first time in years a woman wants a favor from me, and I can’t stomach the idea.

“Mr. Jankowski?”

I look up at her. Her smooth face is two feet from mine. She looks me in the eye, waiting for an answer.

“Oh, all right. But don’t expect me to talk to anyone,” I say, waving a hand in disgust.

And I don’t. I sit and listen as Old Liar McGuinty talks about the wonders of the circus and his experiences as a boy and I watch as the blue-haired old ladies lean toward him and listen, their eyes growing misty with admiration. It drives me completely berserk.

Just as I open my mouth to say something, I catch sight of Rosemary. She’s on the opposite end of the room, bending over an old woman and tucking a napkin into her collar. But her eyes are on me.

I close my mouth again. I just hope she appreciates how hard I’m trying.

She does. When she comes to retrieve me after the tan-colored pudding with edible-oil-product topping has made its appearance, sat for a while, and been removed, she leans down and whispers, “I knew you could do it, Mr. Jankowski. I just knew it.”

“Yes. Well. It wasn’t easy.”

“But it’s better than sitting alone at a table, isn’t it?”

“Maybe.”

She rolls her eyes toward heaven again.

“All right. Yes,” I say grudgingly. “I suppose it’s better than sitting alone.”

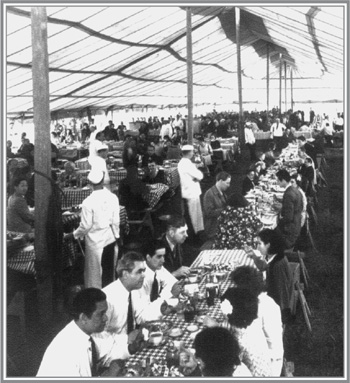

COURTESY OF THE PFENING ARCHIVES, COLUMBUS, OHIO

Fourteen

It’s been six days since Marlena’s accident, and she has yet to reappear. August no longer comes to the cookhouse for meals, so I sit conspicuously alone at our table. When I run across him in the course of looking after the animals, he is polite but distant.

For her part, Rosie is carted out through each town in the hippopotamus wagon and then displayed in the menagerie. She has learned to follow August from the elephant car to the menagerie tent, and in return for this he has stopped beating the hell out of her. Instead, she trudges alongside him, and he walks with the bull hook snagged firmly in the flesh behind her front leg. Once in the menagerie, she stands behind her rope, happily charming the crowds and accepting candy. Uncle Al hasn’t actually said so, but there don’t appear to be any immediate plans to attempt another elephant act.

As the days pass I grow more anxious about Marlena. Each time I approach the cookhouse I hope that I’ll find her there. And each time I don’t, my heart sinks.

I

T’S THE END

of another long day in some damned city or other—they all look about the same from a railroad siding—and the Flying Squadron is preparing to pull out. I’m lounging on my bedroll reading

Othello

and Walter is on his cot reading Wordsworth. Queenie is tucked up against him.

She lifts her head and growls. Both Walter and I jerk upright.

Earl’s large bald head pokes around the edge of the doorframe. “Doc!” he says, looking at me. “Hey! Doc!”

“Hi, Earl. What’s up?”

“I need your help.”

“Sure. What is it?” I say, putting my book down. I shoot a glance at Walter, who has pinned the squirming Queenie against his side. She’s still grumbling.

“It’s Camel,” Earl says in a hushed voice. “He’s got trouble.”

“What kind of trouble?”

“Foot trouble. They’ve gone all floppy. He kind of slaps them down. His hands aren’t so great neither.”

“Is he drunk?”

“Not at this particular moment. But it don’t make no difference nohow.”

“Well damn, Earl,” I say. “He’s got to see a doctor.”

Earl’s forehead crinkles. “Well, yeah. That’s why I’m here.”

“Earl, I’m no doctor.”

“You’re an animal doctor.”

“It’s not the same.”

I glance at Walter, who is pretending to read.

Earl blinks expectantly at me.

“Look,” I say finally, “if he’s in bad shape, let me talk to August or Uncle Al and see if we can get a doctor out in Dubuque.”

“They won’t get him a doctor.”

“Why not?”

Earl straightens in righteous indignation. “Damn. You don’t know nothin’ at all, do you?”

“If there’s something seriously wrong with him, surely they’ll—”

“Throw him off the train, is what,” says Earl definitively. “Now, if he was one of the animals . . .”

I ponder this for only a moment before realizing he’s right. “Okay. I’ll arrange for a doctor myself.”

“How? You got money?”

“Uh, well, no,” I say, embarrassed. “Does he?”

“If he had any money, do you think he’d be drinking jake and canned heat? Aw, come on, won’t you at least have a look? The old feller went out of his way to help you.”

“I know that, Earl, I know that,” I say quickly. “But I don’t know what you expect me to do.”

“You’re the doctor. Just have a look.”

In the distance, a whistle blows.

“Come on,” says Earl. “That’s the five-minute whistle. We gotta move.”