Water for Elephants (26 page)

Read Water for Elephants Online

Authors: Sara Gruen

“It’s not me. It’s a friend of mine. He’s having problems with his feet and hands. And other stuff. He’ll tell you when we get there.”

“Ah,” says the doctor. “Mr. Rosenbluth led me to believe that you were having difficulties of a . . . personal nature.”

The doctor’s expression changes as he follows me down the track. By the time we leave the shiny painted cars of the first section behind, he looks alarmed. By the time we reach the battered cars of the Flying Squadron, his face is pinched in disgust.

“He’s in here,” I say, hopping into the car.

“And how, pray tell, am I supposed to get in?” he says.

Earl emerges from the shadows with a wooden crate. He jumps down, sets it in front of the doorway, and gives it a loud pat. The doctor gazes upon it for a moment and then climbs up, clutching his black bag primly in front of him.

“Where’s the patient?” he says, squinting and scanning the interior.

“Over there,” says Earl. Camel is huddled against a corner. Grady and Bill hover over him.

The doctor walks over to them. “Some privacy, please,” he says.

The other men scatter, murmuring in surprise. They move to the other end of the car and crane their necks, trying to see.

The doctor approaches Camel and crouches beside him. I can’t help noticing that he keeps the knees of his suit off the floorboards.

A few minutes later, he straightens up and says, “Jamaica ginger paralysis. No question about it.”

I suck my breath in through my teeth.

“What? What’s that?” Camel croaks.

“You get it from drinking Jamaica ginger extract.” The doctor puts great emphasis on the final three words. “Or jake, as it’s commonly known.”

“But . . . How? Why?” says Camel, his eyes desperately seeking the doctor’s face. “I don’t understand. I’ve been drinking it for years.”

“Yes. Yes. I would have guessed that,” says the doctor.

Anger rises like bile in my throat. I step up beside the doctor. “I don’t believe you answered the question,” I say as calmly as I can.

The doctor turns and surveys me through his pince-nez. After a pause of a few beats he says, “It’s caused by a cresol compound used by a manufacturer.”

“Dear God,” I say.

“Quite.”

“Why did they add it?”

“To get around the regulations that require that Jamaica ginger extract be rendered unpalatable.” He turns back to Camel and raises his voice.

“So it won’t be used as an alcoholic beverage.”

“Will it go away?” Camel’s voice is high, cracking with fear.

“No. I’m afraid not,” the doctor says.

Behind me, the others catch their breath. Grady comes forward until we’re touching shoulders. “Wait a minute—you mean there’s nothing you can do?”

The doctor straightens up and hooks his thumbs in his pockets. “Me? No. Absolutely not,” he says. His expression is compressed as a pug’s, as though he’s trying to close his nostrils through facial muscles alone. He picks up his bag and edges toward the door.

“Hold on just a cotton-pickin’ moment,” says Grady. “If you can’t do anything, is there anyone else who can?”

The doctor turns to address me specifically, I suppose because I’m the one who paid him. “Oh, there’s plenty who will take your money and offer a cure—wading in oil slush pools, electrical shock therapy—but none of it does a lick of good. He may recover some function over time, but it will be minimal at best. Really, he shouldn’t have been drinking in the first place. It is against federal law, you know.”

I am speechless. I think my mouth may actually be open.

“Is that everything?” he says.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Do . . . you . . . need . . . anything . . . else?” he says as though I’m an idiot.

“No,” I say.

“Then I’ll bid you good day.” He tips his hat, steps gingerly onto the crate, and dismounts. He walks a dozen yards away, sets his bag on the ground, and pulls a handkerchief from his pocket. He wipes his hands carefully, getting in between each finger. Then he picks up his bag, puffs out his chest, and walks off, taking Camel’s last scrap of hope and my father’s pocket watch with him.

When I turn back, Earl, Grady, and Bill are kneeling around Camel. Tears stream down the old man’s face.

“W

ALTER

, I

NEED

to talk to you,” I say, bursting into the goat room. Queenie raises her head, sees that it’s me, and sets it back on her paws.

Walter sets his book down. “Why? What’s up?”

“I need to ask a favor.”

“Well, go on then, what is it?”

“A friend of mine is in a bad way.”

“That guy with jake leg?”

I pause. “Yes.”

I walk over to my bedroll but am too anxious to sit down.

“Well, spit it out then,” Walter says impatiently.

“I want to bring him here.”

“What?”

“He’s going to get redlighted otherwise. His friends had to hide him behind a roll of canvas last night.”

Walter looks at me in horror. “You have got to be kidding.”

“Look, I know you were less than thrilled when I showed up, and I know he’s a working man and all, but he’s an old man and he’s in bad shape and he needs help.”

“And what exactly are we supposed to do with him?”

“Just keep him away from Blackie.”

“For how long? Forever?”

I drop to the edge of my bedroll. He’s right, of course. We can’t keep Camel hidden forever. “Shit,” I say. I bang my forehead with the heel of my palm. And then again. And then again.

“Hey, stop that,” says Walter. He sits forward, closing his book. “Those were serious questions. What would we do with him?”

“I don’t know.”

“Does he have any family?”

I look up at him suddenly. “He mentioned a son once.”

“Okay, well now we’re getting somewhere. Do you know where this son is?”

“No. I gather they aren’t in touch.”

Walter stares at me, tapping his fingers against his leg. After half a minute of silence he says, “All right. Bring him on over. Don’t let anyone see you or we’ll all catch hell.”

I look up in surprise.

“What?” he says, brushing a fly from his forehead.

“Nothing. No. Actually, I mean thank you. Very much.”

“Hey, I got a heart,” he says, lying back and picking up his book. “Not like some people we all know and love.”

W

ALTER AND

I

ARE

relaxing between the matinée and evening show when there’s a soft rapping on our door.

He leaps to his feet, knocking over the wooden crate and cursing as he keeps the kerosene lamp from hitting the floor. I approach the door and glance nervously at the trunks laid end-to-end across the back wall.

Walter rights the lamp and gives me the briefest of nods.

I open the door.

“Marlena!” I say, swinging the door farther open than I intend to. “What are you doing up? I mean, are you okay? Do you want to sit down?”

“No,” she says. Her face is inches from mine. “I’m all right. But I’d like to speak to you for a moment. Are you alone?”

“Uh, no. Not exactly.” I say, glancing back at Walter, who’s shaking his head and waving his hands furiously.

“Can you come to the stateroom?” Marlena says. “It won’t take but a moment.”

“Yes. Of course.”

She turns and walks gingerly to the doorway. She’s wearing slippers, not shoes. She sits on the edge and eases herself down. I watch for a moment, relieved to see that while she moves carefully, she’s not limping obviously.

I close the door.

“Man, oh man,” says Walter, shaking his head. “I nearly had a heart attack. Shit, man. What the hell are we doing?”

“Hey, Camel,” I say. “You okay back there?”

“Yup,” says a thin voice from behind the trunks. “Reckon she saw anything?”

“No. You’re in the clear. For now. But we’re going to have to be very careful.”

M

ARLENA IS IN

the plush chair with her legs crossed. When I first come in, she’s sitting forward, rubbing the arch of one foot. When she sees me, she stops and leans back.

“Jacob. Thank you for coming.”

“Certainly,” I say. I remove my hat, and hold it awkwardly to my chest.

“Please sit down.”

“Thank you,” I say, sitting on the edge of the nearest chair. I look around. “Where’s August?”

“He and Uncle Al are meeting with the railroad authority.”

“Oh,” I say. “Anything serious?”

“Just rumors. Someone reported that we were redlighting men. They’ll sort it out, I’m sure.”

“Rumors. Yes,” I say. I hold my hat in my lap, fingering its edge and waiting.

“So . . . um . . . I was worried about you,” she says.

“You were?”

“Are you all right?” she asks quietly.

“Yes. Of course,” I say. Then it dawns on me what she’s asking. “Oh God—no, it’s not what you think. The doctor wasn’t for me. I needed him to see a friend, and it wasn’t . . . it wasn’t for

that.”

“Oh,” she says, with a nervous laugh. “I’m so glad. I’m sorry, Jacob. I didn’t mean to embarrass you. I was just worried.”

“I’m fine. Really.”

“And your friend?”

I hold my breath for a moment. “Not so fine.”

“Will she be okay?”

“She?” I look up, caught off-guard.

Marlena looks down, twisting her fingers in her lap. “I just assumed it was Barbara.”

I cough, and then I choke.

“Oh, Jacob—oh, goodness. I’m making an awful mess of this. It’s none of my business. Really. Please forgive me.”

“No. I hardly know Barbara.” I blush so hard my scalp prickles.

“It’s all right. I know she’s a . . .” Marlena twists her fingers awkwardly and lets the sentence go unfinished. “Well, despite that, she’s not a bad sort. Quite decent, really, although you want to—”

“Marlena,” I say with enough force to stop her from talking. I clear my throat and continue. “I’m not involved with Barbara. I hardly know her. I don’t think we’ve exchanged more than a dozen words in our lives.”

“Oh,” she says. “It’s just Auggie said . . .”

We sit in excruciating silence for nearly half a minute.

“So, your feet are better then?” I ask.

“Yes, thank you.” Her hands are clasped so tightly her knuckles are white. She swallows and looks at her lap. “There was something else I wanted to talk to you about. What happened in the alley. In Chicago.”

“That was entirely my fault,” I say quickly. “I can’t imagine what came over me. Temporary insanity or something. I’m so very sorry. I can assure you it will never happen again.”

“Oh,” she says quietly.

I look up, startled. Unless I’m very much mistaken, I think I’ve just managed to offend her. “I’m not saying . . . It’s not that you’re not . . . I just . . .”

“Are you saying you didn’t want to kiss me?”

I drop my hat and raise my hands. “Marlena, please help me. I don’t know what you want me to say.”

“Because it would be easier if you didn’t.”

“If I didn’t what?”

“If you didn’t want to kiss me,” she says quietly.

My jaw moves, but it’s several seconds before anything comes out. “Marlena, what are you saying?”

“I . . . I’m not really sure,” she says. “I hardly know what to think anymore. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about you. I know what I’m feeling is wrong, but I just . . . Well, I guess I just wondered . . .”

When I look up, her face is cherry red. She’s clasping and unclasping her hands, staring hard at her lap.

“Marlena,” I say, rising and taking a step forward.

“I think you should go now,” she says.

I stare at her for a few seconds.

“Please,” she says, without looking up.

And so I leave, although every bone in my body screams against it.

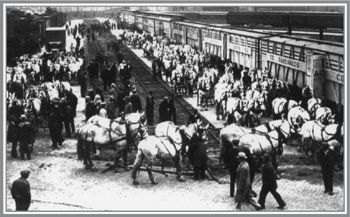

COURTESY OF THE PFENING ARCHIVES, COLUMBUS, OHIO

Fifteen

Camel spends his days hidden behind the trunks, lying on blankets that Walter and I arrange to cushion his ruined body from the floor. His paralysis is so bad I’m not sure he could crawl out even if he wanted to, but he’s so terrified of being caught that he doesn’t try. Each night, after the train is in motion, we pull the trunks out and lean him up in the corner or lay him on the cot, depending on whether he wants to sit up or continue lying down. It’s Walter who insists he take the cot, and in turn I insist that Walter take the bedroll. And so I am back to sleeping on the horse blanket in the corner.

Barely two days into our cohabitation, Camel’s tremors are so bad he can’t even speak. Walter notices at noon when he returns to the train to bring Camel some food. Camel is in such bad shape Walter seeks me out in the menagerie to tell me about it, but August is watching, so I can’t return to the train.

At nearly midnight, Walter and I are sitting side by side on the cot, waiting for the train to pull out. The second it moves, we get up and drag the trunks from the wall.

Walter kneels, puts his hands under Camel’s armpits, and lifts him into a sitting position. Then he pulls a flask from his pocket.

When Camel’s eyes light on it, they jerk up to Walter’s face. Then they fill with tears.

“What’s that?” I ask quickly.

“What the hell do you think it is?” Walter says. “It’s liquor. Real liquor. The good stuff.”