Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (12 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

It's not as though the New York waterfront ever was a place for ordinary citizens to walk much. Boys hung around it for fun and risk, jumping into the East River as their swimming hole, and those who made their living in the port felt comfortable at the river's edge. But except for the Battery, at the island's tip, there was very little opportunity along the water

for strolling or recreation. It was not until the mid-1890s that a few downtown recreation piers and the first, rough version of Riverside Park were opened.

In the twentieth century the edges of Manhattan remained remote from the average New Yorker's everyday path, for the simple reason that the rapid transit system didn't extend that far. The main subway lines traversed the finger-shaped island in a north-south direction, rather than going east-west; also, the subways generally followed the densest residential or retail patterns, which left out the waterfront. Without a subway to take you to the far western or eastern edge, any riparian encounter would have to come after an excursion on foot, making it a more intentional,

marginal

experience. You might be a solitude-loving poet or an escaping thief or someone who lived nearby in one of the reconverted warehouses, but you could not be a member of a crowd, except in those rare, fiesta-like situations when the city embraced the river, usually for its unobstructed sightlines: Fourth of July fireworks, the Brooklyn Bridge or Statue of Liberty centenary. The very avidity with which millions of New Yorkers poured into the waterfront on those occasions suggested what an anomaly it was for them to be there, and only accentuated their usual indifference to the river's edge.

NOW I PASS BY PIER 40, at West Houston Street. This enormous, fifteen-acre concrete bunker traversing three city blocks, probably the last substantial investment the Port Authority made on the island before it became crystal-clear that Manhattan's port was doomed, was built to handle cargo freight, and when it opened, in 1950, it was the largest precast structure in the world. A victim of bad timing, it sat redundant on the waterfront twenty years later. Thereafter it became a gargantuan parking lot—much-needed, by the way, in Lower Manhattan, especially for long-term commuters—that holds more than 2,000 cars and dozens of buses and trucks. It remains an immensely tantalizing site to planners, community activists, and utopian urban dreamers. The Van Alen Institute sponsored an architectural competition, which attracted 141 entries; the winning designs used all or parts of the existing structure, in some cases as a kind of picturesque scrim, leaving only the frame and opening the façade

to the river breezes. For a while it was set to house a Home Depot superstore; now all the alternatives have been put on hold.

I brood about what might have been here, the proposal to build a new satellite Guggenheim art museum on Pier 40, designed by Frank Gehry. A tour-de-force, billowy wave of a building by the maestro of Bilbao at water's edge would have been magnificently dramatic, and where more suitably than at the cusp of two art-conscious neighborhoods, Greenwich Village and SoHo?

*

But it was shot down by the local community planning board, which had long had its eye on the Pier 40 site for recreational uses (never mind that Hudson River Park and all of Battery Park City's recreation spaces were in the vicinity), and which did not appreciate the high-handed, empire-expansionist style of the Guggenheim's director, Thomas Krens, who had failed to consult the community before announcing the plan to the press. To me, the Gehry Museum proposal for Pier 40 was a casualty of a decentralized local planning process, by which what serves the city as a whole often takes a backseat to a community's parochial agenda.

I walk along the edge of Pier 40 next to the terminal building, where benches are set up and an old man is fishing. The sun flashing on the water, the sound of the slapping waves, idyllic: It does make a difference, getting a hundred feet out, away from the noise of the city. I try to think why I feel so comfortable on this pier, compared with some of the new sliver piers, which make me feel exposed and anxious. Of course! The side of the terminal building acts like a street-wall, giving the open space shape, structure, limit. All this emphasis on “open space” is not good for a native New Yorker like myself, who gets vague agoraphobia with no surroundings to hem him in.

A Gehry-designed Guggenheim at Pier 40 would have set a good precedent for a highly visible public building on the waterfront. Unlike London, with its Houses of Parliament along the Thames, or Paris, where the Louvre's palaces front the Seine, New York's waterfront has a dearth of major public buildings. Its reason for being was commerce, not imperial display, so it turned the edges over strictly to port activities. “Virtually every

foot of shoreline,” wrote Kevin Bone in his superb book

The New York Waterfront,

“was occupied by some kind of maritime building: basins, docks, piers, wharves, and seawalls, as well as the headquarters of traders, haulers, shipbuilders, blacksmiths, rope makers, riggers, oyster merchants, brewers, carpenters, and all other conceivable maritime support trades.… [A] gateway village between the metropolis and the sea, for many, this tidewater frontier town was the only New York they knew. It had its own hotels, bars, and brothels, as well as at least one floating church.”

*

It was certainly a better site than the one chosen next, near the South Street Seaport, which would never have survived an environmental review process and which has since been jettisoned.

One reason why exploring the waterfront is such a choppy, mystifying experience today is that you are walking over the bones of that commercial ghost town. There are still shards of it, in the form of the funkiest hotels and bars and (I assume) brothels you can imagine. Take the Liberty Inn Motel on Tenth Avenue and Fourteenth Street. I have always been fascinated by this modest, three-story, brick-faced, triangular structure, like a black-sheep offspring of the Flatiron Building: what is it doing out there, all by itself, near the water? It used to be known as a “hot sheet” hotel: a friend told me she would, in her youthful, promiscuous days, take her pickups from the clubs there. Today I force myself to go in and poke around, as a good reporter must. There is no lobby, just two chairs and a staircase leading up to the guest rooms; on one chair slumps an emaciated black woman, chin buried in chest, apparently nodding out; behind a Plexiglas divider an acne-faced Asian desk clerk eats a hero sandwich and chats on the phone. Misery. A set of rules posted beside the check-in desk states, “Guests must leave room together.”

“What do you want?” asks the desk clerk behind the partition.

“I'd like to see a room. Some friends of mine are coming to town and I thought I might put them up here.” The clerk looks me up and down: blue tweed jacket, white shirt, an obvious lie. She goes back to her friend on the phone. I wonder how far to push the masquerade. “I'll come back later,” I say, leaving with relief. Surely the reader can imagine the kinds of rooms upstairs, without my having to inspect the decor.

Nor do I check out the remaining S&M/gay bars in the area, though I well remember how, at the height of the Stonewall era, this whole “west coast” of Greenwich Village was turned over nightly to men having sex in beef, poultry, and pork storage trucks, the irony of the term “meat-packing district” lost on no one. The writer Michael Lassell elegized that epoch in

an essay for the anthology

New York Sex:

“Once upon a time the riverfront at the westernmost edge of Greenwich Village was a place for queer pioneers to lean between the uprights of the elevated highway, trolling for trade.… For decades, fearless, defiant men sucked dick and butt-fucked in the huge warehouses that loomed above the now-rotting planks that are off-limits big-time.… Nowadays the waterfront is ‘Hudson River Park,’ a hunk of to-be-developed green belt that is still a totally botched West Side Highway expansion. The once-dangerous turf has sprouted rules, regulations, and little green put-puts driven by dickless pissants in ugly uniforms.”

ONE OF THE THINGS I LIKE about the waterfront is that it is ill-defined and still in transition. Maybe it's not such a bad idea for New York to hold on to incomplete zones that inspire dreams and anxieties. If you walk around Manhattan's waterfront today, you encounter a bewildering mix of edge-experiences that range from the blighted to the elegant, to the postmodernist pastiche, to the unfinished, to near wilderness. The sense you most often get is that everything the city doesn't want to deal with, everything “repressed,” has been pushed to the water's edge. Salt mounds, auto salvage shops, beer-can recycling companies, defunct factories with smashed windows peeling in the sun, parking-violation tow pounds, huge parking lots for all the sanitation trucks on earth, S&M bars, public housing. Not for nothing do so many storage warehouses exist along the river, sheltering the old family dining sets, college books, and other obligations to the past that space-pinched New Yorkers think they need to hold on to, but are halfway to abandoning.

The repressed flourished best in the cracks of the decaying port, especially once it had begun to fall into ruin. The novelist Andrew Holleran once considered this phenomenon in an essay for

Christopher Street

magazine: “ ‘Why do gays love ruins?’ I said to my friends.… ‘The Lower West Side, the docks. Why do we love slums so much?’

“ ‘One can hardly suck cock on Madison Avenue, darling,’ said the alumnus of the Mineshaft, curling his lip as we strolled down that very street.… ‘When the shoreline is made pretty by city planners, and …the meatpacking district is given over entirely to boutiques and cardshops—then

we'll build an island in New York Harbor composed entirely of rotting piers, blocks of collapsed walls, and litter-strewn lots.”

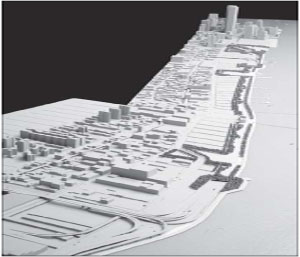

Today the meatpacking district is barely holding on, invaded as it is by boutiques and bistros. Meanwhile, the Greenwich Village waterfront is being transformed into a civic place, Hudson River Park. The Hudson River Park Trust is admirably, even radically, attempting to push forward a new public work along the water, from TriBeCa to 59th Street, a task every bit as difficult as building Central Park or Riverside Park—more so, actually, because it does not have landscape architects of genius like Olmsted and Vaux to oversee its design, or a powerful official like Robert Moses to cut through the red tape. It has only the conviction that New Yorkers want to get to the water, and that it is the city's manifest destiny to do so.

The former West Side Highway, now known as Route 9A, has been reconfigured as an “urban boulevard”—the model most often cited for it is Park Avenue—with traffic lights every three blocks and plantings in the middle. No longer a ten-lane, sixty-five-miles-per-hour speedway, now it is to be a more “diminutive,” eight-lane, optimally 25 mph glide. But it still looks and feels like a highway, not a boulevard. Nor does it resemble, in any way but the timing of its traffic lights, Park Avenue.

As I walk along the West Village section of the Hudson River Park, I find myself thinking: One of the best things you can do at the water's edge of a city is to make a street. Preferably a narrow street, providing only one car-lane apiece in each direction, so that it does not become another high-speed traffic corridor, but invites strolling, with fairly low-rise buildings that house shops on the ground floor, thereby bringing the vitality of the city to the edge. A promenade, be it in a beachside resort or a waterfront district, becomes energized when the walker can go from looking at the water to ducking into a shop or café on the street side (as in all those fatalistic French 1930s films, where Jean Gabin wanders down to the port to cast longing eyes at a ship leaving for foreign shores, then backs into a bar for a shot of

vin ordinaire

). If you look at photographs of the Manhattan dockside in the early decades of the twentieth century, what you see—and it comes as a shock—is a real street, with automobiles parked two feet from the drink.

I suppose we must concede that West Street is technically a street, just

not a very inviting, well-designed one. Certainly much of the success of the Hudson River Park, at least around SoHo and Greenwich Village, will hinge on what happens across the way, on the building side of West Street. At present it is a ragtag collection of holding-pattern uses: auto parts and garage repair shops, X-rated video stalls, printing firms on their way out, meatpacking plants in their twilight hour, next to boarded-up storefronts. The park will be served greatly if the street across from it becomes a lively area, with cafés and mixed uses and a steady stream of strollers. If it turns into nonstop luxury high-rises with private lobbies, as is already happening in parts of West Street, not so good.

7 EXCURSUS

OUTBOARD, OR THE BATTLE OF WESTWAY AND ITS AFTERMATH

If a city has a memory, then the legacy of discarded infrastructural works forms an important part of that memory.

—HAN MEYER,

City and Port

N

O UNBUILT PROJECT HAS HAD A GREATER IMPACT ON NEW YORK CITY

'

S RECENT HISTORY THAN WESTWAY, THE PLAN TO SUBMERGE THE OLD SIX

-

LANE HIGHWAY under hundreds of acres of parkland and development along the West Side waterfront. The last three decades of the twentieth century were dominated by inflamed arguments for and against it, and, as a new century opens, the consequences of its defeat continue to shape all future development on the waterfront. Westway is the road not taken, and it haunts every choice made in its stead. Which is not to say that the man in the street even remembers it. The paradox of New York is that it is at once famously destructive and forgetful of its past, and forever walking in its oversized footprints. Those who wonder how a great city, capable of doing so much more along its riverfront, came to such an uninspiring compromise—a landscaped transit corridor that calls itself a park, a highway with a non-walkable divider that styles itself a boulevard—will do well to review the history of Westway, before it slides from our memory bank.