Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (8 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

All at once, I wanted to be with my family. My cocoa-colored shirt was flecked with white ash, like birdshit, when I turned in to my daughter's school. Parents crowded the lobby, many picking up their children to take them home. To my way of thinking, school seemed as safe a place for Lily as our house; I saw no reason to take her out prematurely. Cheryl was standing by the door of the multipurpose room, waiting for Lily's class to leave at the end of dance period. When she came out, Lily seemed happily surprised to see me, in midday; I hugged her. She trooped off to her next activity. Cheryl milled around with the other mothers and some of the fathers, who had returned from the financial district: they were all comparing personal accounts, and engaging in that compulsively repetitious dialogue by which an enormity is made real.

A few days later my wife reproached me for having shown up with ash-laden clothing, my shirttails left untucked. She said I could have frightened the children. I replied that I didn't think anyone had even noticed me. But, on some level, her reproach was justified: I was indulging the fantasy of being invisible, I was not being a team player. Some sort of communal bonding had started taking place, foreign to me, beautiful in many respects, scary in others. My wife and I both felt anguished that day and all week, but it was an anguish we could not share. The fault was mine: selfishly, I wanted to nurse my grief at what had been done to

my

city. I mistrusted any attempt to co-opt me into group-think, even conjugal-think.

That New York was the primary target I had no doubt. I felt so identified with my native city that it took a mental wrenching to understand all of America considered itself assaulted. I knew, of course, that the Pentagon had been hit and another plane had gone down in a Pennsylvania field, but I chose to see it as an attack on the values of urbanism, vertical density, secular humanism, skepticism, women's rights, and mass transit. The American flags that started appearing everywhere may have been fitting ways to honor the heroic local firemen and police who died in the line of duty, but the only banner I wanted to fly from my

brownstone window was the orange, green, and white flag of New York City, with its clunky Dutchman and beaver.

People claim that the city will be changed forever by this attack. It is easy to say, less easy to understand exactly how. New York's history has not exactly been a stranger to tragedy. A few days after September 11, I did notice subway riders being unusually polite to each other, whether out of communal solidarity and respect for human life, or from wariness of the Other's potential rage, I cannot say. That nuance has faded. No New Yorker expected America's warm feelings toward the city to last very long; it was like getting licked by a large, forgetful St. Bernard dog. Meanwhile, the towers that anchored Lower Manhattan are gone,

pfft.

I ask myself how I have been changed personally. On the morning of September 12 I awoke and remembered immediately what had happened, like a murderer returning to the horror of his altered moral life. I sensed I would, perhaps, never be the same, though not necessarily better. I have never bought the idea that suffering ennobles people. Rather, I expect that this awful experience will add scar tissue to the other atrocities in life, like the death of one's parents, the illnesses of one's children, or the shame of one's nation (My Lai, for example), sorrows over which one has no control but that cause, for all that, the deepest regrets.

THE VOID LEFT in the heart of Lower Manhattan by the September 11 tragedy provoked considerable speculation about what should go there. Inevitably the discussion took on awkward tones from the start: the bad taste of dreaming design utopias or sending résumés around while bodies were still being excavated. Nevertheless, we all knew that after a suitable pause, with predictable wrangling between officials and developers, the area would have to get rebuilt. It was too important to lie fallow.

Much of the discussion seemed to me misdirected. How avant-garde the new buildings should be, what architectural brand should go on the site, mattered less to me than what sort of public environment ought to be created there. What would the streetlife be like? How would pedestrians, tourists, workers experience it on the ground? How could we most gracefully integrate the new complex into the surrounding area?

Lower Manhattan has a specific character. It is not Midtown, with its regular, flat-terrain blocks of high-rise density. It is the oldest part of New York, and the “grid” down there (if you can call it that) is more casually variable, the streets smaller and narrower, given to sudden surprises and winding perspectives. To the east are the canyons of Wall Street, a dramatic topography in itself, which it might be possible to prolong. Whatever gets built, there already seems a commendable push to extend the east-west streets river to river, as they originally ran, before the World Trade Center created an obstruction.

In many ways the World Trade Center marked a significant break with New York City's spatial form. Its superblock interrupted the circulation of pedestrians; its introverted, mall-life retail was hidden from the street; and it buried its transportation modes (the PATH and subway lines) deep within. It may have made an impressive contribution to the skyline, but it was not very effective at street level.

The design by Daniel Libeskind and Associates that was finally chosen to replace the World Trade Center, after a bitterly contested architectural competition, may or may not work better at street level, may or may not be severely compromised by the pressures of conflicting clients and a weak economy; it's too early to tell. Practically speaking, there is no reason why some of the 13 million square feet of offices destroyed in the attack shouldn't be replaced, though, partly because there is already a glut of office space downtown, I would prefer a more varied mix of office, residential, cultural (opera house or museum), retail, and transportation uses. Whatever gets built, there are better ways of doing it than towers set off in plazas.

Thousands of commuters will again pour into the area daily, as they have in the past. Some sort of terminal or overt transportation structure seems in order, to express with aplomb their entry to the city's downtown area. Ideally, you could extend commuter rail from the Midtown terminals to the Lower Manhattan area, which would greatly enhance the attractiveness of the Financial District as a working environment.

A memorial must and will go up; the area is, after all, a massive gravesite. But I confess I am leery of the aesthetic range of contemporary monuments, pulled as they are between realist kitsch and tepidly tasteful

abstraction, and I despair of any memorial doing justice to the victims and their families. As for the idea that a really spectacular memorial to September 11 would rejuvenate Lower Manhattan's tourist business by itself, that seems to me craven if not delusional.

The greatest tribute we could pay those who gave their lives on this site would be to make it into a convivial, life-affirming, urbane place, which would most aptly express New York's street-smart character. (But all such rhetoric on the subject, however well intended, finally makes one gag.)

4 EXCURSUS THE HARBOR AND THE OLD PORT

And has it really faded from the port, the painful glamour? Has it really gone from them, the fiction that was always on the movements of the liners in and out the upper bay? Or has it merely retreated for a while behind the bluffs of the New Jersey shore, to return to us again to-morrow and draw the breast away once more into the distance beneath Staten Island hill?

—PAUL ROSENFELD,

Port of New York

F

OR THE MAJORITY OF NEW YORKERS, EVEN NATIVEBORN, THE HARBOR IS AN ABSTRACTION

:

ONE WOULD BE HARD PRESSED TO SAY WHAT EXACT TERRITORY OF LAND and water it encompassed. When the state agencies promoting tourism speak of a “Harbor Park” connecting the Battery, the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, Snug Harbor in Staten Island, and Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in Brooklyn into one ferry-bound entity, they are essentially imposing a hopeful verbal scrim over what is to most people an empty stage. We know the harbor used to dominate the city's consciousness, but we don't feel it anymore. I am skeptical that tourists with limited time in New York—say, a week—would give a whole day to exploring this harbor concept, by taking ferries hither and yon to island monuments far removed from Broadway. But since there are many repeat tourists to New York, perhaps they might try it on a later visit; and happily so, less because of what they might find at the various stops than because there are few ways to experience New York as pleasurably as by looking at it from the water.

The recent proposal by the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance for a harbor loop ferry system that would make up to fifteen stops in the Upper Bay, as an extension of the mass transit system, is exciting as well as sensible. Like a set of extra highways already in place, the waterways could cut down on travel time, expense, and pollution. But beyond whatever logistical, financial, and political problems may arise in instituting such a desirable plan, the harbor would have to be understood again by the public as more than an archaic abstraction—as something functionally real.

*

I wonder what Ernest Poole would have made of such a turnabout. Poole, a journalist of the progressive camp, who wrote crusading pieces about the East Side slums, chose in his first novel,

The Harbor,

to portray the port of New York as the very symbol of reality. Poole used the terms

harbor

and

port

interchangeably, and when he wrote the novel, the port of

New York was the largest in the world, not only in the amount of commerce it handled, but also in the length of its available waterfront.

*

*

The last writer to understand it that way was probably Alfred Kazin, who penned a 1986 essay called “The Harbor Is My New York.” Can you imagine a young writer-about-town using that title today?

The Harbor

(1915) is a

Bildungsroman

about a young man, Billy, who grows up above the Brooklyn waterfront, overlooking “a harbor that to me was strange and terrible,” with its “sweaty, hairy dockers and saloons.” His father owns a warehouse on the docks, and by Oedipal extension Billy identifies everything that is patriarchal, brutal, and materialistic with the harbor. “From that day the harbor became for me a big grim place to be let alone—like my father. A place immeasurably stronger than I—like my father—and like him harsh and indifferent.” His ex-schoolteacher mother, who “had come to hate the harbor,” encourages Billy toward idealism and the finer things in life. At the same time, he is drawn to the ragged waterfront kids, and mesmerized by the sight of “a big fat girl half dressed, giggling and queer, quite drunk” who seems to represent the life-force at its greasiest and sexiest. Later, leaving no metaphor untried, Billy says, “I was a toy piano. And the harbor was a giant who played on me till I rattled inside.”

Poole works the harbor symbolism so painstakingly that there is scarcely room for the characters to come alive. Though the novel has its moments, it's not a great book. I read it twice, wanting desperately to find a lost masterpiece, so that I could rediscover and defend the neglected Ernest Poole. As it happens, he writes with florid enthusiasm, like a poor man's O. Henry or John Reed, in a boy-scoutish style (trying not to get ahead of his character's naïveté) that has aged badly. Still, I find intriguing its one-track-mind fascination with the New York harbor as an indomitable juggernaut that can never be stilled—especially since it

has

been stilled.

*

In 1910 the U.S. Treasury Department, for purposes of customs law, established its demarcations as “including all the territory lying within the corporate limits of the cities of Greater New York and Yonkers, N.Y., and of Jersey City, N.J., and in addition thereto all the waters and shores of the Hudson River and Kill von Kill in the State of New Jersey from a point opposite Fort Washington to Bergen Point Light and all the waters and shores of Newark Bay and the Hackensack River lying within Hudson County, N.J., from Bergen Point Light to the limits of Jersey City.” This area had a waterfront of 771 miles, of which 362 miles were developed with 852 piers. Manhattan alone had a developed waterfront (measuring the area around the piers) of about 76 miles.

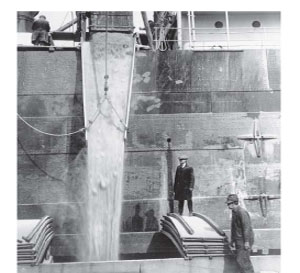

IN

1915,

THE SAME YEAR

The Harbor

appeared, the Russell Sage Foundation published Charles B. Barnes's

The Longshoremen,

probably the first in-depth study ever done of American dockworkers. The author's sympathy for the men he studied was apparent. Conveying with statistics and sober prose the dangerous, unremitting working conditions these men endured, Barnes reported that a longshoreman handled about three thousand pounds per hour, that the heavy lifting led frequently to hernias and muscular exhaustion, that the pressure to load or unload ships as rapidly as possible resulted in crews working thirty to forty hours straight, and that the ensuing fatigue increased the chances of accident.