Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (3 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

A QUICK START-UP OF MANNAHATTA

M

ANHATTAN IS SHAPED LIKE AN OCEAN LINER OR LIKE A LOZENGE OR LIKE A PARAMECIUM

(

WHAT REMAINS OF ITS PROTRUDING PIERS, ITS CILIA

)

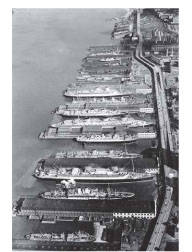

OR LIKE A GOURD or like some sort of fish, a striped bass, say, but most of all like a luxury liner, permanently docked, going nowhere.

The Japanese of the early eighteenth century had a word,

ukiyo,

for the “floating world” of courtesans, actors, and rich merchants and their spoiled progeny who made up the town's most visible element. Manhattan is a floating world, too: buoyant as balsa, heavy as granite. The reason skyscrapers developed so readily on this spit of earth is that its bedrock, composed of Fordham schist, Inwood marble, and White Mountain gneiss,

was strong enough to withstand any amount of drilling. You can still bruise your ego against Manhattan's rough cheek. Like other island or aqueous cities—Istanbul, Venice, Hong Kong—it has a brash, arrogant energy far disproportionate to its size, and an uneasiness about domination by larger forces which it always tries to conceal.

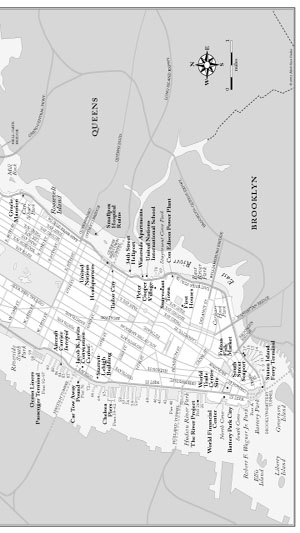

The island of Manhattan extends about thirteen miles in length, and two miles across at its widest point. It rests in the arms of the Hudson (whose lower branch, alongside Manhattan, used to be called the North River) and the East River. Properly speaking, the East River is not a river but a saltwater estuary or strait, a leg of the sea. It connects with the Harlem River (also a tidal strait), which flows between the Bronx and the northern tip of Manhattan.

Seventy-five thousand years ago the glaciers began descending into the New York area, crushing the land, scooping out valleys and depositing boulders. The Ice Age was a period that, we know of a certainty, was extremely cold. Twenty thousand years later it was still rather cold; twenty thousand years after that, not quite so cold; twenty thousand years from that point, fairly chilly but approaching a tolerable coolness, suitable for human habitation. A mere eleven thousand years ago, as the glaciers were retreating and the seas rising, the first inhabitants arrived. In the final centuries of the Ice Age, these Paleoindians, as archaeologists call them, hunted mastodons with spears. Then they disappeared. In the Early Archaic period (10,000–8,000 B

.

P.), the Hudson River was still a fjord, the city's harbor had yet to be formed; in the Middle Archaic (8,000–6,000 B

.

P.), Native Americans began settling in, making tools and harvesting oysters; this was followed by the Late Archaic (6,000–3,700 B

.

P.), by which time the harbor had been formed and the sea levels were close to their current position. Following hard on the Late Archaic was the transitional period (3,700–2,700 B

.

P.), during which nothing very exciting happened, and then the Early and Middle Woodland (2,700–1,000 B

.

P.), a period of considerable pottery-making, hunting, fishing, and trading by the Munsees (a branch of the Lenape), but not much agriculture, surprisingly. This brings us to the arrival of the first Europeans.

The name “Manhattan,” a Munsee tribe word, has been variously ascribed by linguists to mean “island,” “place of general inebriation,” or “place where timber is procured for bows and arrows.” Washington Irving

gave a more partial, tongue-in-cheek explanation in his

A History of New York:

“MANNA-HATA—that is to say, the island of Manna; or in other words—‘a land flowing with milk and honey.’”

When Henry Hudson first sailed into the Upper Bay in 1609, searching for a westerly passage to China, he and the crew of the

Half Moon,

a Dutch ship, found a fair approximation to an isle of milk and honey. The natives met them in canoes with oysters the size of trays. (Later he was murdered by hostile Indians, but that's another story.) In 1624 the Dutch established an outpost at the southeastern tip of the island. Adriaen van der Donck, an early settler, described a place of streams and waterfalls and running brooks; copious wild turkeys that slept in the trees; a multitude of trout, striped bass, shellfish, and weakfish; natives “all properly formed and well-proportioned,” who, despite their “particular aversion” to “heavy slavish labor,” managed to grow maize, squash, and watermelon; an air “so dry, sweet and healthy that we need not wish that it were otherwise”; and, most important of all, beavers.

New York was founded on animal skins and oysters.

*

The Dutch West India Company, granted a monopoly by the Netherlands government, ran New Amsterdam as a trading post, pure and simple. Almost immediately it attracted a polyglot, continental population, with forty languages spoken, and blacks, Jews, Portuguese, and Samoans intermingling. The Dutch found it a somewhat disappointing investment—less profitable, from their perspective, than Curaçao. When the British threatened in 1664, pointing cannons at Wall Street, the Dutch surrendered without a fight. Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor, had

wanted to defend it, but cooler, more mercantile heads prevailed. The next day they were doing business with the enemy.

*

One can never say enough about oysters. “The statistics on oysters alone were staggering. The area that includes New York Harbor and parts of the lower Hudson estuary had 350 square miles of oyster beds. Some biologists have argued that these beds alone produced more than half the world's supply of oysters,” write Anne-Marie Cantwell and Diana diZerega Wall, the authors of

Unearthing Gotham,

a fine book about the archaeology of New York City. They wonder, however, how important oysters were to the Native Americans in the Archaic periods, since “a pound of shelled oyster meat adds up to only 475 calories. If that is the case, and if oysters did play a major role in the Archaic diet, then an average adult would have had to eat a staggering number of oysters, about 250 a day, to maintain daily caloric requirements.” More likely, they speculate, oysters were eaten as a delicacy, or as a fallback food in starvation times.

Once upon a time, New York and New Jersey were part of the same British colony; then the Duke of York severed them—to pay off a gambling debt, according to legend. (Since then, politicians in Trenton and Albany have each tried to pretend that the Hudson River's problems affected only their own state lines.) Both the Dutch and the British did not hesitate to tinker with Manhattan's shoreline, extending the waterfront streets outward through landfill, and giving love handles to its arrowhead profile at the island's southern tip. Swamps were filled in, piers built along the East River.

Very quickly the geographical advantages of New York's port were grasped: that it had a deep channel, sheltered from the ocean's rages; that it had a choice of two river routes leading to the sea (along either shore of Long Island); that it had a fairly mild climate and was rarely ice-choked in winter, compared with the more northern Boston or Halifax; that it had potentially good access to the western territories. In spite of this superiority to other American ports, it started slowly: in 1770 it ranked fourth, behind Philadelphia, Boston, and Charleston, in total tonnage. Yet its strategic importance seemed so manifest even then that, during the American Revolution, the British sent the largest naval force ever amassed to secure it.

They secured it. Washington's troops were forced to flee under cover of night, silently rowing across the East River, then the Hudson. New York spent most of the war as a Tory port. The British army stationed itself comfortably in Manhattan, drilling on Bowling Green, holding balls and wenching, a situation that may have contributed to the lingering mistrust of New York by patriotic Americans.

An extensive fire—either from sabotage or accident; we may never know—left much to rebuild after independence.

The look of Manhattan, its aesthetic destiny, so to speak, was sealed in 1811 with the approval of the commissioners' grid plan. This arrangement laid out a pattern of crisscrossed parallel bars for all the city's future thoroughfares, from above Houston Street to just below Washington Heights, disregarding any topographical impediments that might get in the way. The prevailing wisdom among today's planners is that it is important to

honor the land's contours, which only goes to show how visionary the city fathers were: they created a New York as eccentrically “intentional” as St. Petersburg, a madly rational scheme imposed on nature. Nor did they have any use for the circles, ovals, and other geometric interventions so loved by Europeans. The commissioners loved the ninety-degree angle, the forthright, egalitarian plod of rectangle after rectangle, extended indefinitely: they would have gridded the sea and stars if given the chance.

One reason the city fathers liked the grid was that it facilitated the orderly sale and development of property. While one hears the Manhattan grid disparaged today as merely a capitalist device for real-estate speculation, to me it is a mighty form, existential metaphor, generator of modernity, Procrustean bed, call it what you will, a thing impossible to overpraise. The architect Rem Koolhaas called it “the most courageous act of prediction in Western civilization.” It inspired Mondrian, Sol Lewitt, Agnes Martin, and that's good enough for me. Those who maintain it makes for monotony are at a loss to account for the vitality of Manhattan street life. They overlook this

particular

grid's power to invoke clarity, resonance, and pleasure through its very repetitions; they ignore the role of Broadway as a diagonal “rogue” street creating dramas of triangulation wherever it intersects an avenue (think, say, of 168th Street, 72nd Street, 59th Street, 42nd Street, 34th Street, 23rd Street …); and they forget variations in block length within the grid, which differentiate the petite, elegant poodle walks of the Upper East Side, say, from the long, punishing treks between avenue corners on the Upper West Side.

The grid pulls you ever forward, along those avenues that are the only true “streams” recognized by the New York pedestrian. Interestingly, the 1811 plan had rationalized its failure to provide for parks and other recreational breathers by stating that the island's river waterfronts would yield sufficient relief.

(The creation of Central Park, which opened in 1859, compensated in part for the 1811 grid plan's failure to provide for recreational spaces. Planted in the midst of the inland crowded streets to which New Yorkers were ever drawn, Central Park was the stroke of genius needed to complete the grid, by offering a counterpoint of man-made Nature: the largest and greenest of rectangles, superimposed on the checkerboard, immeasurably boosting land values; it drew like a magnet to its edges the most prestigious

mansions and apartment buildings. “With the implantation of Central Park,” wrote the historian Richard Plunz, “the morphology of modern Manhattan was firmly established: that of a luxurious center and of a marginal periphery in terms of residential real estate, and quite the opposite in terms of commercial and industrial property. In the Manhattan psyche, Central Park became the ‘waterfront’: a kind of ‘green’ sea. Bourgeois aspirations placed Manhattan in a park, rather than in the sea. Water was its lifeblood, but not its soul.”)

To return to our chronological summary: the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 secured the triumph of New York as a great port, by connecting the Atlantic seaport with the interior, all the way to Lake Erie. While the Erie Canal undoubtedly magnified the port's commercial importance, by bringing flour, wheat, lumber and other commodities from the frontier to the city, and transporting to the hinterlands those niceties of civilization Westerners wanted, other factors besides the canal, argued Robert Greenhalgh Albion in his classic study,

The Rise of New York Port

(

1815–1860

), may have contributed as significantly to the port's ascendance. First, there was the innovation of regularly scheduled ocean liners, such as the Black Ball Line, which contracted to leave at a certain date from New York and arrive at Liverpool on schedule, instead of dawdling from port to port, picking up a full complement of cargo. (Already the city was turning its temperamental impatience, the “New York minute,” to commercial advantage.) Improvements in boat design made for faster ships, such as the famous China clippers. The East River Yards of Manhattan became a major center of quality shipbuilding. The city's banking institutions tied the hinterlands to New York as firmly as had the Erie Canal. Finally, the fact that the steamship was financed and perfected in New York gave the region a head start in that mode of traffic.