Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (53 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

*

The city and state have recently announced their intentions to fix it up as an esplanade.

AS SOON AS THE PAIN in my right thigh had abated, a few weeks later, I resolved to tackle again the Harlem River shoreline, at the same point where I had left off. Perhaps because the Great Saunter had already set the pattern for me of walking south, I decided to start at about East 160th Street and end up around East 90th Street and Gracie Mansion. But unlike the Shorewalkers, who had been forced to hike a good part of that distance on the inland side of the highway, I wanted to explore the very narrow, strange, overgrown waterfront path between the fence and the river, where no one ever seemed to go.

I took along the writer Tom Beller, my ex-student, now friend, and master of that difficult genre, the narcissistic-young-man story. Tom is in his early thirties, very tall, bicycles everywhere, and plays basketball on the playgrounds of New York. The point is, he looks intimidatingly fit, and I feel safe in his company, going into the wilds of the East Harlem water-front—safe enough, anyway, to be free of the persistent looking-over-my-shoulder fear I would feel going through these parts alone.

At the Harlem River Drive, a six-lane highway, we decided to divide our attempt into two parts: first attaining the median, and then aiming for a specific pole on the other side to break our run. We waited for a gap in the traffic and dashed across (not recommended), and climbed over a low fence, finding ourselves on a trash-strewn stretch of paved road between the highway and the river. On the Bronx side, we saw a billboard, with white letters against a black background, which said, KEEP USING MY NAME IN VAIN

.

I

'

LL MAKE RUSH HOUR LONGER

.—

GOD

.

In truth, the traffic on the Major Deegan Expressway looked slow-moving enough to suggest that some major blaspheming had transpired.

The narrow lip of land next to the river ended, and we had to hop over the fence again and walk single-file along the highway, following a narrow, two-foot-wide, raised curb against the oncoming traffic. Given my preferences, I would rather not walk into traffic (should my foot slip, I would fall into a speeding car), but I cherished the sanguine expectation that

the Department of Transportation had at least provided this curb all the way to 96th Street, a hope soon to be disabused. Meanwhile, we were having less of a river experience than an encounter with the modern highway. Tom and I couldn't even pursue a conversation, as we had to walk single-file with the noise of traffic around us. He stopped several feet ahead, and I wondered what to make of the enigmatic set of his body. When I caught up, I saw that the raised curb had given out. Were we to continue walking south, we would have had to hug the edge, facing traffic, without any protection.

We looked over at the water. There was no land alongside it, or even any riprap or rocks to cling to. Tom said it might be possible to “shimmy” for about fifty feet, holding on to the ledge while dangling over the river, until we got to some rocks or pilings. This seemed pointless to me; it hardly qualified as walking the waterfront. Maybe if there were some prize money or a medal waiting for us at the end, I would have attempted it; but this way would be a merely private daredevil stunt.

Across the river loomed Yankee Stadium. “We could swim across,” said Tom.

“I don't know. The East River current can be pretty strong.”

We backtracked to a crossing and dashed over the highway again, near the 155th Street on-ramp, to the inland side. There we found ourselves beside one of the innumerable housing projects that dot the Harlem River: the Colonial Park Houses. Just south of Public School 46, we came upon a rather nice city playground with handball and tennis courts. No one was playing handball that day, but the tennis courts were in full swing: I watched a couple gamely smacking the ball back and forth. The parked vehicles of Highway Department workers took up the last tennis court.

We looked longingly through the playground's chain-link fence toward the river. The highway rose aboveground at this point, and it seemed from our vantage-point that it should be possible to walk underneath the highway and alongside the river, if only we could get over the fence that stood in our way. I asked a middle-aged black man, sunning himself by the handball courts, if there was any opening in the fence, farther on. He seemed appalled at the implied illegality of my question and said, “No, there isn't.” Tom and I walked on a few feet, and spotted a hole in the fenc

ing, the kind that kids or vagrants make. As we were trying to measure whether it would be big enough for adults like ourselves to crawl through, Tom said excitedly, “Look at this!” He thrust his arm though the hole and fished out a pair of wire cutters. It seemed to have been left there expressly for the purpose of snipping a few more notches out of the fence. We were both vastly enthralled by this fortuitous find. One of us, I won't say who, clipped the fence wire twice, making a hole suitable for us to corkscrew our bodies through.

Tom thought about taking the wire cutters with us, but I convinced him it was better karma to leave it there for others.

We were now in a dirt enclosure underneath the highway. Seeing small, Y-shaped footprints in the earth, Tom surmised that the place was used for cockfights. I instantly began envisioning the heat and excitement of these illegal activities, men speaking Spanish, smoking cigars, and betting large bills, when he shamefacedly offered, “But they could be pigeon tracks as well.” On all sides of us, we came up against double fences with razor-wire circles at the top, to discourage climbing farther. It dawned on us that we had backed ourselves into the equivalent of a holding pen in a prison. Even if we were to squeeze our way through a narrow gap in the eastward fence, we would still be facing a sheer seawall drop over the river, with nothing to hold on to.

“We would do it if we had to,” Tom said, regretfully forgoing the challenge.

“Yes, if we were fleeing from the Nazis.”

“Precisely.”

On the southern end, we saw, through the fence, a train yard with Number 3 subway cars, there to be either repaired or turned around. I found this herd of subway cars mysterious and tantalizing. We could have climbed the fence, which was about ten feet high, to investigate them further, but to what ultimate purpose? I was reluctant to test my luck with the third rail again. And so, after the elation of finding the wire cutters, we realized we had no choice but to leave the holding pen, retrace our steps, and go back to the tennis courts.

At the edge of the playground we came into a middle-class, high-rise complex with balconies, most likely private. The grounds looked well kept,

and it had that level of comfort and elegance, including a swimming pool with the sounds of happy children rising as we passed, that you don't usually find in public housing.

Our objective being to return at the first possible opportunity to the river's edge, we luckily happened upon another narrow patch on the waterfront side. A low fence separated it from the highway—the best possible circumstance. This spit of land was quite wild, overgrown with shoulder-high grass. I suddenly remembered the pleasure I'd had as a kid, hiding in the bushes between a street and a fence, and pretending to be an Indian. Of course I was much shorter then, making it easier to conceal myself.

Tom and I plunged through pathless reeds that seemed to require a machete, passing on the way at least a hundred automobile tires that had been dumped there, for Lord knows what reason. Some looked in pretty good condition, new or almost new. Were they surplus stolen goods? Or damaged tires too tedious to dispose of in the normal recycling way? How did they end up here? I thought they must have been tossed over the fence from cars that parked on the highway in the middle of the night, while Tom conjectured that they had been brought over by boats. I did not see how or where the boats could tie up. There were also banged-up car parts strewn about, bottles, and occasionally a pair of underwear. For the most part I was wordlessly engrossed, a kid again on a hike through new and fascinating countryside that could turn up anything.

As we pushed south along the water's edge, we came upon fence after fence in which earlier pathfinders had thoughtfully cut holes for us to squeeze through. We passed an esplanade that had collapsed, many of its octagonal paving stones missing, the supporting structure having caved in from, I assume, shipworm damage. In these gaping holes of the esplanade you could see down to the black, eddying river.

Our attention was drawn to a large sign: THE CONSTRUCTION OF A PORTION OF HARLEM RIVER PRK BIKEWAY BOUNDED BY THE HARLEM RIVER AND HARLEM RIVER DRIVE BETWEEN EAST

135

TH ST AND EAST

139

TH ST

.

After listing the proposed park's features and the names of the politicians responsible, it stated: CONTRACTOR PROMISES TO COMPLETE THIS PROJECT BY JUNE 4, 2002. The deadline had already passed.

At around 130th Street, the land suddenly enlarged, or rather, the highway veered to the west, leaving a free, unimpeded walking space. I was

overjoyed to be able to saunter forward unimpeded, to stroll without interruption, flapping my arms in the afternoon sun, after hours of scratching our way through thorns, fences, and highway crossings. This promontory, delightfully spacious as it was, also looked like a wasteland, with an enormous mound of road salt, the rusting tower of an abandoned concrete batching plant, tons of asphalt chunks, and the twisted remnants of a barge gantry. It felt sinister, blasted, end-of-the-world. A homeless black couple had built an elaborate shanty out of canvas and driftwood, of the sort one might see in Soweto. I remarked to Tom that this desolate cove could be developed into a beautiful beach—it expressed the city's shameful contempt for the residents of Harlem and people of color, to have allowed their waterfront access to deteriorate into a dump, essentially. At the same time, I was unavoidably drawn to this poetic collage of industrial detritus, excited by my discovery of it, and wished there was some way of preserving these picturesque ruins, just as they were.

We came upon some workmen for a private contractor, who had set up tents to handle asbestos. The tents all bore signs warning about toxicity within. The workmen, in orange vest-jackets, seemed nervous about our traversing their area, but lacked the authority to boot us out. One said, “I just want to warn you that last week someone was stabbed to death right around here.”

“That's why I brought my friend,” I said.

Below 125th Street, we came upon the Bobby Wagner Jr. Esplanade, which wound past one public housing project after another, followed by the old parabola-shaped asphalt plant, the Richard Dattner–designed aquacenter, and Gracie Mansion. There we caught the subway downtown.

26 EXCURSUS ODE TO THE PROJECTS

It is all falling indelibly into the past.

—DON DELILLO,

Underworld

I

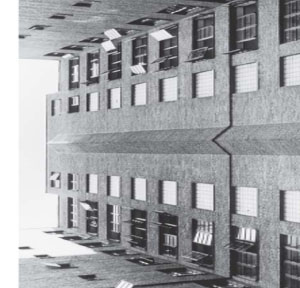

T IS REMARKABLE HOW MUCH OF THE EAST RIVER WATERFRONT IS GIVEN OVER TO PUBLIC HOUSING. WHEN FIRST APPROACHING THE ISLAND FROM THE BROOKLYN, MANhattan, or Williamsburg Bridge, the shoreline of the Lower East Side looks like a solid medieval fortification wall of brick projects. Just past the South Street Seaport starts the succession: the Al Smith Houses, the Rutgers Houses, the LaGuardia Houses, the Vladeck Houses, the Corlears Hook Houses, the Bernard Baruch Houses, the Lillian Wald Houses, the Jacob Riis Houses, up to the Con Edison power plant on East 14th Street. There follows a jump of eighty blocks, given over to hospital

complexes, the United Nations, the Gold Coast of luxury apartment towers, and Gracie Mansion, the mayor's residence. Then the parade of public housing picks up again across 96th Street and continues unabated along East Harlem's waterfront: the Stanley M. Isaacs Houses, the East River Houses, the Woodrow Wilson Houses, the Senator Robert F. Wagner Houses, the Abraham Lincoln Houses, the Harlem River Houses, the Polo Ground Houses, the Ralph J. Rangel Houses. Then a forty-block hiatus occurs for Highbridge Park, only to resume at the northern tip of the island, with the Dyckman Houses.

The sight of all this concentrated public housing on the East River polarizes me: it makes me sad, because the projects are grim-looking, penitentiary in their massive sameness, the antithesis of visual invitation, a severe welcome-mat to place on the waterfront; yet it also makes me pleased to think that there was a time when our government built thousands of units to shelter those in need, and that it continues to operate the buildings at reasonable rents for low-income occupants. I am a little in love with them—with their romantic, quixotic idealism, at least—and the fact that they still make me quiver in uneasiness whenever I brush against their perimeters does not in any way dilute my determination to love them.

At some point, public housing came to be known simply as “the projects,” a term with dementedly futuristic, monumental overtones. One thinks of a mad conceptual architect, covering page after page with drawings of columns and Piranesian spirals. Since the 1980s, there has been a bureaucratic tendency to suppress this term in favor of the more neutral “housing developments.” But proof that it still has legitimacy is that my current telephone book lists the separate estates of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) under the subheading “The Projects.” Let us hold on to this suggestive label awhile longer; it conveys the grandiose idealism present at their conception. They have since become so stigmatized as medinas of despair, that it will take all our imagination to wrench free of that summation and dream our way back to their original promise, before we can assess their current functioning properly.