Wendy and the Lost Boys (12 page)

Read Wendy and the Lost Boys Online

Authors: Julie Salamon

The pinnacle of their Amherst theater career came senior year. They became part of an of-the-moment production of

Peter Pan,

reconfigured as a radical treatise, in which the Lost Boys were hippies. Peter Pan was played by a black man, Tinker Bell by a gay man. Wendy choreographed the play; Gretchen was cast as one of the Lost Boys.

Peter Pan

had always had special significance for Wendy. There was the obvious connection of her name, the link to Sandy and childhood. She had fond memories of starring in a summer-camp production. The story’s magical quality of perpetual innocence continued to be part of Wendy’s aura, even though her perceptions about people could be ironic and quite adult.

It was during the Amherst production that Gretchen recognized Wendy’s talent—not as a writer but as a choreographer. All those years at the June Taylor dance studio had left an imprint. Gretchen was impressed by the elaborate sequences Wendy plotted out for

Peter Pan

(especially the tap routine she choreographed for a song called “Wendy”)

.

Right before graduation Gretchen was informed that Smith wouldn’t give her credit for a class she’d taken at Hampshire College, which had just opened with an experimental program. But Smith would accept credits for a dance course Gretchen found at California State University at Long Beach, California, that she could complete the summer after senior year. She asked Wendy to come along.

It didn’t take much convincing for Wendy to exchange the gloomy prospect of rattling around New York, being nagged by Lola while avoiding and pursuing James Kaplan. A summer by the beach, with a continent between all that, seemed perfect. This would become another pattern of Wendy’s. If someone invited her somewhere, she went. Like her parents, she kept in motion. (Morris was said to wear out three pairs of guaranteed-for-life ripple-soled shoes a year, probably a Wasserstein exaggeration but accurately reflecting his love of walking.)

She set out for California with Gretchen and Nancy Steele, a friend of Gretchen’s who was a dancer, too. The three of them drove across the country—or rather Gretchen and Nancy drove. Wendy didn’t have a driver’s license; this wasn’t unusual for someone raised in New York City.

Wendy was that peculiar breed, the New York provincial—the type who can rattle off the names of Broadway directors and Greek gods and has visited the major European capitals but has never ordered french fries at a drive-in window. For her the California world of fast-food joints like Taco Bell and Jack in the Box was exotic and mystifying. She had a dorm room but spent most of her time at the little apartment that Gretchen rented a block from the beach. They swam in the ocean and entered a go-go-dancing contest at a hotel. They ogled their gorgeous dance professor, William Couser, an avant-garde choreographer who blended primitive, folk, and jazz techniques and used performance to reflect on the condition of the black race.

Wendy liked Gretchen, but it was Ruth Karl who, in absentia, became her partner in misery, as well as an appreciative audience for her adventures and concerns that summer. In long letters they commiserated with each other about their failed attempts at losing weight and their lack of direction. It was hard for Wendy to talk about dieting with lithe Gretchen, who was sympathetic but who could also gorge without noticeable consequence.

When Wendy sent Ruth a detailed explanation of a lecture she’d heard about the relationship between movement, self-image, and the potential for change, Ruth gave a comforting reply:

My dearest Wendella,

Your exercise on self-image and movement was fascinating but I forget what movement means. I’ve reached unprecedented dissipation. You would have been so proud of me today. I consumed a whole 39 cent Hershey Almond Chocolate Bar, among other things. I’ve abandoned all hopes of will power. Tomorrow my 3 week supply of super duper time capsule Benzedex diet pills is arriving. Better living through chemistry.

I hope to find a waitress job tomorrow, if I can summon up the energy. Then I’ll have a little “bread” for the move to the big city. . . .

A Mini heavy

I think life is a pile of shit. I will sell my soul, body and anything else I can get my hands on to construct a safer little world of my own. I don’t think I can change the world. Even if I could and did, people would fuck it up again. Have I turned into a no-good capitalist pig? If so, do you still like me? Also, I hate men. And most women.

Love, Ruth

Wendy replied in kind:

Dear Ruth,

Got jealous of your dissipation so Gretchen and I went out and outdid you—a Hershey Almond bar and P’nut butter. Eat Your Heart Out. I am marshmallow woman. Each day I vow to the goddess of thin woman . . . that I will become asparagus queen—and then a suggestion from a friend and I’m back in candy land. To put it bluntly, Lola was right. I’m not a mensch.

D

espite her self-flagellation, Wendy enjoyed herself that summer. She said she was happy. “I

am

living the good life,” she wrote. “Protein, dance and fun in neon city. It is a bit like being in a health spa with decorations furnished by McDonald’s. . . .”

Yet she knew that her romance with L.A. was just a summer fling. As the return home to New York approached, she remained worried about her future.

“Did you ever think you could be great

if only,

” she wrote to Ruth. “I live in the fantasy where that

if only

doesn’t exist. In reality it looks larger every day.”

Part Two

BECOMING A WRITER

1971-80

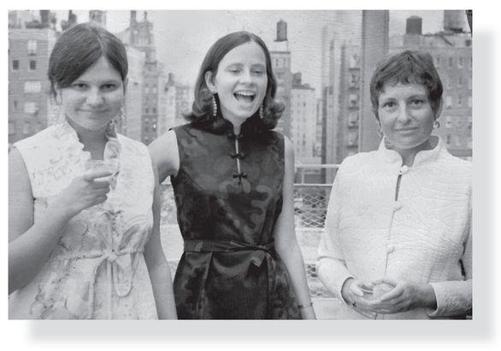

WENDY’S SIBLINGS SEEMED TO KNOW WHERE THEY WERE GOING,

BUT AFTER GRADUATING FROM HOLYOKE SHE WAS FLOUNDERING.

HERE WITH SISTERS SANDY AND GEORGETTE.

Six

THE FUNNIEST GIRL IN NEW YORK

1971-73

“Wendy, you make me want

to blechhh,” Lola said to her in exasperation one day. “You know what blechhh is?”

Wendy knew exactly what “blechhh” was, especially after Lola put her hand to her mouth and pretended to retch.

“Why don’t you do something?” Lola snapped.

Wendy decided to make a play for maternal sympathy.

“Mother, I’m not feeling well, I’ve been feeling sad lately.”

A futile gesture.

Lola turned to Wendy, ready to pounce. “What have you got to be sad about? Did your husband die? Did your son get sick?”

Up until that moment, Wendy had no idea that Lola had had a first husband, much less one who’d died.

In the torrent that followed, she forgot to ask her mother who that husband was—or knew better than to delve into family secrets, or was afraid to pursue a line of questioning whose answers might be too disturbing.

“No one has put into their children what I put into you, and this is the thank-you I get?” Lola said. “Who knows? Maybe I didn’t do the right thing. Maybe I shouldn’t have been there. You know, if I was your age—if I had been born when you were born—I could have been a dancer or a designer. I wouldn’t have wasted my life putting it all into you!”

Wendy couldn’t remember any more of the conversation, except that Lola’s hands were shaking, that she was crying, and that she grabbed her bag and slammed the door, yelling as she left, “I have to go kick-kick. I have to work you out of my system!”

It’s fair to say that in the fall of 1971, after Wendy returned from California, things were not going well. Despite her persistent self-doubt and her inability to be svelte, she had always felt she held a charmed spot in the family, the delightful child who entertained everyone else. Now she had a new role—the loser. What did she have to show for her Seven Sisters education? No prospects for a job and no husband on the horizon—or not one she wanted.

Look at her siblings! Sandy was remarried, to a man named Peter Schweitzer, who had been a fellow executive at General Foods and had movie-star looks, a Robert Redford type. She continued to rise through the corporate ranks. Wendy always said her sister had invented Tang, the powdered fruit drink the astronauts took to the moon. Actually, she’d managed the brand, less sexy but important enough, a breakthrough job for a woman. Sandy had accomplished all that and had a baby girl, Jenifer, born Thanksgiving weekend, 1969. Her second child, Samantha, was born in 1972, also during the holidays. Each time Sandy returned to work two weeks after giving birth. She subverted her company’s mandatory pregnancy leave by renting a hotel room across from General Foods headquarters and installing her secretary there, so she could keep working.

Georgette and Albert were still living in New Haven, where Georgette had provided Lola and Morris with two granddaughters, Tajlei and Melissa.

Bruce, only three years older than Wendy, already had a joint degree from Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School. While he was still in law school, he coedited a book with Mark J. Green, known as a top lieutenant in Nader’s Raiders, the collection of disciples who flocked to Washington, D.C., to work for Ralph Nader, the consumer advocate. Bruce himself had worked for Nader one summer while he was at Harvard.

The Green-Wasserstein collaboration, called

With Justice for Some: An Indictment of the Law by Young Advocates,

is an idealistic collection of thirteen essays by law students and recent law graduates, manuscript typed by Bruce’s wife, Lynne. In a passionate editors’ note, Green and Wasserstein discuss their aim: “The chapters of this book probe the failures of contemporary law, offer proposals for change, and describe some victims—blacks, women, students, servicemen, consumers, the poor.”

By the time Wendy returned from college, Bruce had changed course, moving away from worry about institutional injustices toward his future in mergers and acquisitions. He won a fellowship to study law and economics at Cambridge University and spent a year abroad with Lynne. After that he assured Lynne he would be ready to start a family. He wanted no fewer than five children—a dynasty, like the Rothschilds.

No wonder Wendy felt like taking to bed.

“I know I have to leave here,” she wrote to Ruth Karl. “The dust on the piano was shaped into ‘Wendy get married’ when I woke up this morning.”

The family got together frequently. Outsiders (and the children’s spouses fell into this category) were treated warmly but were aware that they would never be part of the inner circle. “I felt absolutely welcomed into the family,” said Peter Schweitzer, Sandra’s second husband. “But it was very difficult. You’re in a room where you’re almost constantly competing. They’re all high achievers, highly intelligent. There wasn’t a lot of goofing around playing touch football. You always had to be at your intellectual best. It can be tiring.”

None of the children were exempt from Lola’s sharp appraisals, although Wendy couldn’t help but notice that she was often criticized for flaws that went unnoticed in Bruce. Like Wendy, Bruce was overweight and sloppy, and he had the same flat feet as his younger sister. In his case these attributes—along with his poor eyesight—became pluses, exempting him from the draft. In Wendy’s case . . . blechhh.

The previous spring Wendy had been talking to David Rimmer about their post-graduation plans. They’d met at Amherst, where they both were involved in theater. He was shaggy-haired and lanky, with off-center, almost-handsome good looks. After Kent State, and the subsequent eruptions on campus, Rimmer had contacted local high schools and community colleges in the area. He offered to produce some of their Amherst plays about Vietnam and racism and other political issues. Wendy became part of the traveling consciousness-raising dramatic troupe, working as a crew member.

They became even closer friends senior year, when Rimmer directed the

Peter Pan

that Wendy had choreographed.

With graduation weighing on them, the two sat around with a group of friends wondering what they were going to do the following year. Rimmer mentioned a possibility. One of the political plays he’d taken on the road at Amherst was written by Israel Horovitz, a playwright whose work had been making a stir in New York. He’d won several prizes, including an Obie Award for

The Indian Wants the Bronx,

which starred an impressive emerging young actor, Al Pacino, also awarded an Obie for his performance. Rimmer had gotten to know Horovitz, who liked the student director’s moxie and took him under his wing. Horovitz was teaching a playwriting workshop at City College in New York in the fall, part of a new master’s program in creative writing. He told Rimmer he should sign up.

Rimmer didn’t have an agenda beyond “why not?” When Wendy told him she was going to apply to law school, he said, “I’ve got this playwriting workshop thing with Israel. You want to join me?”

It was an easy decision. She, too, had nothing else to do.

Things were looser then. The English department at City College had just announced the creative-writing program in April, five months before it was to begin. Besides Horovitz’s drama course, the teachers included Gwendolyn Brooks, the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet, and Joseph Heller, whose 1961 novel

Catch-22

had become a cultural phenomenon, its wild black humor and antiwar attitude resonating with the Vietnam generation. Only twenty students were to be admitted.

N

ew York City, 1971, was Fear City, dirty and dangerous. The crime rate had been soaring throughout the 1960s; 1,823 murders were committed the year Wendy came home, up from 548 in 1963. Racial and generational tensions were high. Two years earlier Mario Puzo’s bestselling novel

The Godfather

elevated the Mafia to mythic status, with its romantic/realistic rendering of the illicit world of drugs and racketeering. Though the story was set in the 1940s and ’50s, the book’s cynical vision of capitalism and crime meshed with the country’s general sense of unease.

As the war in Vietnam dragged on, grit and disillusion had become the cultural norms, in politics and in art. The top-secret Department of Defense documents that became known as the “Pentagon Papers”—which detailed U.S. involvement in Vietnam since 1945—were leaked to the press by Daniel Ellsberg that summer. In November David Rabe’s

Sticks and Bones

opened at the Public Theater, about a soldier’s return from Vietnam and his family’s inability to comprehend what their blinded son has gone through or who he has become. The play was a sequel to Rabe’s

The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel,

the brutal portrait of a young American soldier in Vietnam, written from Rabe’s experience. The Oscar for Best Picture that year went to

The French Connection,

William Friedkin’s streetwise, nerve-racking action movie about cops and narcotics smugglers

For the new college graduate, New York could be exciting or dispiriting, depending on the day, but in either case it was not the same place Wendy had left behind. Both she and her city had gone through sobering changes. She’d been a girl when she left; now she was supposed to be an adult, or on the way to becoming one.

Through David Rimmer, Wendy had grown somewhat friendly with Israel Horovitz. In addition to taking his playwriting seminar, a couple of times she baby-sat for his three children (one of whom was Adam Horovitz, who later became Ad-Rock, of the band the Beastie Boys). Rimmer had been living at the Horovitz house but then had a falling-out with the playwright, who was in the middle of a grim divorce—and living up to his reputation as a moody character given to tantrums. Rimmer ended up leaving New York a few months into the playwriting program.

I

n Joseph Heller, Wendy found a kindred spirit. She met him a decade after the publication of

Catch-22.

By then Heller had been declared a genius and

Catch-22

was acknowledged as a landmark work. There had been much critical revisionism since the original mixed reviews that had praised Heller’s ingenuity and questioned his craftsmanship, like the verdict issued by the

New York Times Book Review:

“Joseph Heller . . . is like a brilliant painter who decides to throw all the ideas in his sketchbooks onto one canvas, relying on their charm and shock to compensate for the lack of design.”

Heller was another Brooklyn Jew who believed that comedy—the nuttier the better—was the way to cope with distress (as well as monumental issues, like the irrational cruelty existing in man and nature). He grasped the flashes of brilliance lurking in Wendy’s writing, even though her early sketches were haphazard and occasionally incoherent.

After reading several of her papers, he told her, “Wendy this is fabulous, you’ve got a real talent here. You should stay with this.”

Heller gave Wendy something more important, perhaps, than any single lesson he might have imparted in class or perceptive comment he might have scribbled on a paper. He made her feel that she had something special to offer. This endorsement was a powerful antidote to the sense of failure that weighed on her, a load exaggerated by her having graduated without distinction and being home without any apparent goal in mind.

In future years Wendy would tell variations on an anecdote that indicated how much Heller’s approval meant to her. The story, in all its incarnations, also showed how adept she became at turning a memory—real, imagined, or embellished—into an amusing scene with a sly or outrageous punch line that simultaneously promoted and diminished herself:

Version One: Joseph Heller took her to some sort of party and introduced her as “the funniest girl in New York,” and Wendy promptly threw up.

1

Version Two: She was having lunch with Joseph Heller at a fancy restaurant. Someone stopped by the table, and Heller introduced his student. “This is Wendy Wasserstein, the funniest girl in New York.” She responded by throwing up.

2

Version Three: She was with a friend who introduced her to the novelistJoseph Heller as a brilliantly funny writer. She responded to his request, “Say something funny, Wendy,” by barfing on his coat.

3

T

he classes with Horovitz and Heller awakened something profound in Wendy. At City College she began to work on the approach that would become her signature—mingling memory, observation, reality, and fiction. The “Cuisinart method,” Bruce called it. “She had perfect-pitch memory for conversations, but then she’d put them in the Cuisinart and they’d come out in random ways,” he said. “So if you knew all these things, they’d come out having nothing to do with the particular fact lines.”