Wendy and the Lost Boys (8 page)

Read Wendy and the Lost Boys Online

Authors: Julie Salamon

Kathy worked up the courage to call him, to tell him she had a friend he should go out with. As Jimmy, who preferred James, remembered it, Kathy made certain to let him know that her friend had been dating someone and that

she

had broken up with him, not vice versa.

James agreed to meet Wendy. He wasn’t quite smitten, but he liked her. Not a beauty, he thought, but she had a cute freckle face. He liked her intelligence and sensitivity and even her insecurity, which made him feel protective. They began to date.

The boys at Horace Mann were said to believe that the girls at Calhoun were “easy,” but in 1967 it was unusual for high-school girls to “go all the way.” Fear of unwanted pregnancy was a large concern; abortion wouldn’t be legal in New York for another three years and nationwide until 1973. But that didn’t stop sex and romance from being a primary extracurricular activity for teenagers—at the very least as a major topic of conversation.

Wendy pursued James, or so he felt. “She was making a play for me,” he said. “She could be aggressive when she wanted things.”

He liked her well enough to invite her to the Horace Mann senior prom, and to make out with her, but he didn’t want to be exclusive. There was another girl he was dating at the time, whom he was more interested in, but that girl was less interested in him.

He was bothered by Wendy’s tendency to put on weight, and he told her so. In subsequent decades he recalled his rude frankness ruefully; by then he was a middle-aged man, eighty pounds heavier than he’d been in high school. He regretted calling her a “fat Polack,” a teenage boy’s cruel term of endearment.

As he saw their relationship that spring, it was an enjoyable interlude before they both left home. They experimented with sex within the zone of safety, meaning no intercourse. They went to movies and had long talks but apparently didn’t communicate as well as they might have.

“I saw her as someone I’d gone out with several times,” said James. “The prom, I guess, to her indicated something of a commitment.”

Both of them had plans to go abroad that summer. Wendy was leaving for the World Youth Forum trip, to represent American teenagers, an idea she took seriously but also found amusing.

James was heading for Turkey, to be part of the Experiment in International Living, another idealistic program meant “to foster peace through understanding, communication, and cooperation.” Young people were dispersed to other countries, to immerse themselves in foreign cultures for a few weeks, a process that included living with local families.

In a later generation, participation in such programs would become more common. In 1967 not many teenagers, even from upper-middle-class families, traveled abroad on their own. For Wendy the fact that she and James had chosen similar ways to spend their summer demonstrated a commonality of spirit and purpose. Besides, he was the perfect specimen to bring home to Lola: a bright, Yale-bound Jewish boy with prospects—and she had caught him without being thin. They had similar backgrounds—fathers in the textile business, mothers with artistic urges (his mother was a sculptor). Wendy believed she wanted a family; Jimmy Kaplan was a viable candidate, if and when she decided to marry.

For James their summer plans simply provided a fortuitous opportunity to bring a casual relationship to an end.

They both managed to be wrong.

T

he summer of 1967 was hot and hateful. Dozens of American cities—including Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Newark—erupted in violence, called “riots” or “uprisings,” depending on one’s perspective. Three years earlier Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964; people living in inner-city slums failed to see racial progress. Martin Luther King Jr. preached nonviolence, but the street wanted action, not words. The system, springboard to success for the Wasserstein family, oppressed the black community, descendants of slaves, the immigrants who had made the journey against their will.

The American heartbreak spread around the world. America, slayer of Hitler, defender of freedom, had become the racist imperialist, mired in the Vietnam War.

White children whose families had prospered in the United States began reassessing. Was everything they’d been taught an illusion?

Summer of hate, “Summer of Love.” Tens of thousands of young people converged on Haight-Ashbury, the “hippie” section of San Francisco, for a giant be-in. The counterculture rebellion was on, celebrating LSD, free love, universal harmony, tie-dye, and youth. The national media acted as public-relations operative, setting in place the mythology of a generation.

For Wendy, it was Summer Abroad with the World Youth Forum, whose participants were hardly rebels. If anything, this group of earnest, open-minded young Americans provided good public relations toward Europeans growing more and more disillusioned with U.S. foreign policy. The trip was grueling and exhilarating, densely scheduled with meetings and activities.

They toured factories and strolled through gardens in Germany, visited salt mines and got drunk at a folk festival in Austria. They ate Sabbath dinner with Jews in Nuremberg, after attending a service, not in a synagogue but a small room on the ground floor of an apartment house. Behind the Iron Curtain, in Yugoslavia, they met contemporaries in a youth work camp and interviewed the editor-in-chief of the

Vjesnik

newspaper agency in Zagreb. They missed a scheduled lecture at the Institute for the History of the Workers’ Movement, but did meet with labor leaders at a factory that manufactured radios and televisions, to discuss the self-management of Yugoslavian workers. They saw

La Bohème

in Venice, where they also ate lunch with an Italian countess, who was an avid environmentalist. Their photograph appeared in a German newspaper. They were introduced to mayors and other politicians everywhere they went.

Wendy made an important connection on the trip. Abigail J. Stewart of Staten Island, another World Youth Forum winner, was attending Mount Holyoke College that fall. When Abby and Wendy discovered they were both going there—Wendy had been taken off the waiting list before graduation—they became fast friends.

“That trip was a very big experience for most of us,” said Abby, speaking as the adult she became, a professor of psychology and women’s studies. “None of us had experienced that kind of independence, in terms of being served wine and making decisions of where to go and what to do. There was the freedom, dealing with other languages and cultures and each other. . . . We saw ourselves as the intelligentsia. That was all our self-construction, but we were very involved in our self-construction.”

Before they made their farewells, she and Wendy agreed to write to Mount Holyoke, to ask if they could be roommates. They got along well, and neither of them knew anyone else at Holyoke. The age of the computerized roommate match hadn’t yet arrived. They wouldn’t know if their request had been granted until they arrived on campus a few weeks later.

THE 1960S SEEMED TO HAVE BYPASSED MOUNT HOLYOKE, OR SO IT SEEMED TO WENDY WHEN SHE ARRIVED IN THE FALL OF 1967.

Four

GRACIOUS LIVING

1967-68

The four-year period that encompassed

Wendy’s years as a student at Mount Holyoke College, 1967 to 1971, would be remembered by a generation as a transformative period when attitudes seemed to change overnight.

From Wendy’s vantage point—South Hadley, Massachusetts, autumn 1967—it seemed that overnight was taking forever.

She and Abby Stewart arrived at Mount Holyoke primed for experience, pumped by their summer adventures abroad, invigorated by the larger events that had turned the evening news into a nightly drama filled with war, riots, and sexual revolution.

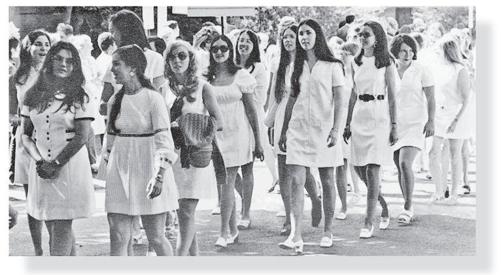

It didn’t take them long to realize they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. They didn’t find the all-female intellectual citadel they had anticipated, and certainly not a campus fomenting radical thought. Instead they encountered a hothouse of girlieness, stuck in the 1950s, filled with bright women who seemed desperate to land a husband. In class it was sometimes hard to pay attention to the professor because of all the knitting needles clicking, as girls made sweaters for their boyfriends. Seniors didn’t obsess about graduate school much; most were far more concerned about whether they would be leaving Holyoke with engagement rings on their fingers.

On their first day of school, the entering freshman heard this piece of advice when they gathered in the gymnasium: “This is where you can take sports, and you might want to think about golf and tennis, games you can play that would be good for your husband’s business.”

They were assigned Big Sisters to counsel them, as well as Elves, anonymous sprites who would leave the occasional gift for them, small tokens like candy.

Wendy and Abby were taken aback, though they shouldn’t have been. The freshman handbook for the Class of 1971 offered incoming students a guide to the rules and customs that Mount Holyoke “girls” were meant to respect. Nothing epitomized the mind-set better than the section on “Gracious Living”:

On Wednesday evening and Sunday noon, the scene is set. . . . For these two meals, girls dress up more than usual and wear stockings and heels. “Gracious” provides a break in the everyday routine—gives you a chance to discard those Levi’s and sweatshirts in favor of a paisley hostess skirt or a knit suit. Dinner is by candlelight, and coffee is served in the living room afterwards.

In addition, there were instructions on how much to eat, what to wear, how to behave, and whom to date.

MEALS: . . . Some are so adept at this that they soon gain the proverbial “freshman ten” pounds and find that that new silver lamé mini-dress is a bit too skimpy after all.

ATTIRE: Robes and curler caps may be worn to breakfast. Skirts are required for dinner with the exception of Sunday supper.

DORM LIFE: . . . The Work Chairman . . . coordinates and assigns the “chores” each student is expected to do once a week. The jobs are small and easily performed: helping out with the dishwashing at one meal, or sitting bells, which involves being on hand at the front desk to answer the telephone and receive callers. . . .

DATING: During the week the Mount Holyoke world is books and classes, coffee at the C.I., bridge when you should be studying, and staying up all night talking to the girl down the hall. It’s a girl’s world where no one really cares if you don’t have time to set your hair. Come Friday, however, it’s a different scene. The social whirl begins as suitcases are snapped shut and girls take off for Amherst, Williams, Wesleyan, Yale, Dartmouth, Princeton, Harvard, Brown, Trinity, Cornell and Colgate among others. At the same time boys begin arriving from these places for mixers and parties. From Friday to Sunday, it’s a man’s world.

Advance warning or not, Wendy and Abby felt gypped.

Wendy had been drawn to the school’s pedigree as one of the Seven Sisters. Abby had succumbed to the romance of Emily Dickinson, who’d been a student there.

Both of them had been seduced by Mount Holyoke’s picture-postcard New England campus, located in the tiny town of South Hadley, tucked in the hills of western Massachusetts, part of the lush Connecticut River Valley. They’d heard the history, of how the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary was started in 1837 by Mary Lyon, a remarkable schoolteacher who’d crusaded to make higher education available to women. It was crucial, she felt, that the curriculum be as rigorous as those in men’s colleges, and available to women of all backgrounds.

The fantasies they had conjured didn’t include Gracious Living and being handed cloth napkins with instructions to fold them at the end of each meal and tuck them into an assigned cubbyhole.

They lived in 1837 Hall, the dormitory named for the year of the college’s founding. Despite its historic name, the dorm was another disappointment, a boxy modern rectangle, overlooking the Lower Lake. Soon everything that had lured them became suffocating. With its old-fashioned brick architecture, nestled in a landscape of lovely wooded paths and secluded ponds, the college was a portrait of rural civility that quickly felt too snug, too staid.

Wendy and Abby became closer than they might have, bonded by their feelings of being outsiders.

They understood that the Ivy League and the Seven Sisters emphasized academic excellence but hadn’t quite grasped the way the schools perpetuated class preservation. There was an unstated expectation that students would form the old-boy and old-girl networks that would, after graduation, become advantageous connections in business, academia, politics, and high society. Mount Holyoke did have a long history of social responsibility—the school graduated its first African-American student in 1883. Yet diversity hadn’t advanced past tokenism. In 1967 there were a handful of African Americans—eighteen “Negro” freshmen out of a class of 486—and not many Jews. The latter fact was unsettling to Wendy, who’d been surrounded by Jews throughout her education.

The college was more traditional than any school she had attended. Abby had already become politicized and was beginning to develop a strong feminist point of view. She found the idea of Gracious Living ridiculous.

The two girls, united by alienation, responded in very different ways. Abby, the future academic, took refuge in her studies. Wendy, the future playwright, entertained the other “misfits” who gathered in her room to listen to her vast record collection of Broadway show tunes and eat and talk. She seemed to live in her flannel nightgown and never to comb her hair. Everything became grist for a funny story, even her grades, which were the worst she’d ever had, C’s and D’s, even in the subjects she liked, English and history.

She made it all seem like a lark. When she and Abby took zoology together, they invented songs to help them memorize things. In the middle of the night, Abby watched Wendy tap-dance the sixteen functions of the liver (with a nod to Mrs. Janovsky, her dance teacher at Ethical Culture).

Abby was in awe of Wendy’s sophistication. For Abby, a girl from Staten Island, Manhattan was the celestial city and Wendy lived there. She knew rare things. In her nimble way, she dropped references that were foreign to Abby: the music of Benjamin Britten, the medieval mystery

Play of Daniel.

Despite the frustrations she’d caused her teachers at Calhoun, Exeter, and Andover, Wendy had been paying attention.

It never occurred to Abby that her roommate was seriously struggling. Wendy joked about her bad grades, but she didn’t seem that upset. Only once did Abby glimpse real distress, when Wendy got back a paper she’d labored over, an analysis of the William Faulkner short story “The Bear.” After all her hard work, she received a D.

Abby also didn’t notice they were drifting apart. In the spring they decided to room together again sophomore year. One day, without telling Abby why, Wendy said she’d changed her mind. She would be living in Pearson Annex, with a group of their friends from 1837. Abby was hurt and perplexed.

More than thirty years would pass before Abby learned the reason Wendy had reneged. The celebrated playwright had recently published a collection of essays,

Shiksa Goddess,

and sent the book to her former roommate, with whom she’d stayed in touch over the years. Abby had remained true to her academic interests. She earned her Ph.D. in psychology at Harvard and was a professor at the University of Michigan, in psychology and women’s studies, as well as the director of the Institute for Research on Women and Gender.

Too busy to read Wendy’s book when it arrived, she then forgot about it for several months.

One day she remembered

Shiksa Goddess.

She was about halfway through when she began to read the opening paragraph in an essay called “Women Beware Women.”

“Women are the worst,” Wendy wrote. “I will rot in hell for saying that. My toes will gnarl inward into tiny hooves, and I’ll never dare to get another pedicure. All right. All right. Women are kind, decent, nurturing, the best friends women could ever have—until they’re not. Then women can be the absolute worst.”

Abby continued until she reached page 117 of the book, the middle of the essay. She stopped abruptly, feeling the years vanish. Once again she was a freshman at Mount Holyoke, wondering what she’d done to upset Wendy.

Two sentences explained everything.

“I moved out on my college roommate at a time when she thought we were the closest of friends,” wrote Wendy. “She was too smart; I was flunking.”

Then Abby realized how hard it must have been for Wendy to admit how bad she’d felt about her grades. Her nonchalance had been an act.

Abby called Wendy and apologized for taking so long to get to the book. She added, “Wendy, I didn’t know you had something in there about us.”

Wendy laughed and said, “I wondered if you’d ever notice.”

S

oon after they’d met, Abby had become aware of what she thought of as Wendy’s “precocity worship.” She often mentioned that Sandy and Bruce had entered Michigan when they were sixteen.

Franny and Zooey

came up in conversation more than once, Wendy consciously comparing her family to J. D. Salinger’s fictional whiz kids. She told Abby how much she admired Bruce, who was a senior at Michigan, heading for Harvard Law School in the fall, and only twenty years old. He was the executive editor of the

Michigan Daily

and had his own column called “Publick Occurrences,” after the independent newspaper published in Boston in 1690 and shut down by the British after one edition.

He and Sandy were the smart ones, Wendy said. She couldn’t measure up to them.

Wendy depended on her sisters, frequently calling them to chat. Staying in touch required some effort in the era before cell phones and e-mail. In conversations with her roommate, Wendy was reverent toward Sandy, reciting her achievements as a woman executive, in awe of her independence, talent, toughness—the sum of which spelled success. Toward Georgette, Wendy was affectionate but critical of her conventional path. Sandy represented accomplishment, Georgette represented family happiness. Wendy said she felt pulled in both directions, but it was Sandy whom she idolized.

Abby had gotten a hint of the family’s complexity during the World Youth Forum trip. There were those strange postcards from Lola—“Eating and thinking of you,”—which were funny and affectionate in one way, needling in another.

Wendy helped the long train and bus rides pass effortlessly, with her humorous tales of Lola and Morris and her siblings. She referred to another brother, Abner, who was sick and had been sent away. Wendy called him a “family secret.” She said she didn’t understand why he had essentially been obliterated by the family, who never referred to him. Abby saw that Wendy was troubled by this, but she didn’t press for details, and none were offered.

When the girls returned from Europe, before college began, Abby visited Wendy at her apartment and met Lola and Morris. Abby felt she had stepped inside a vaudeville routine. There was no food in the house; Lola was always going off to dance class. Even their Thanksgiving meal was ordered in. The Wassersteins were different from Abby’s parents, a lawyer father and a housewife mother.

Nothing about their behavior helped Abby understand Wendy’s focus on her siblings’ achievements—not at the time. “Morris was very, very sweet,” said Abby. “It was very hard to get past sweet. He was a very lovely man who was very loving.” Lola seemed more critical, Abby observed, but she found Wendy’s mother “more strange than driven.”

C

amilla Peach, the head of hall for the 1837 dorm, was not amused by Wendy. In her evaluation she noted:

Responsibility toward work in hall—poor

Offices held in hall—none

Qualities of leadership observed—none

“Wendy is a problem,” Mrs. Peach wrote. “She is unkempt to say the least. Defiant when spoken to. I understand she’s very bright. Her cooperation in the Hall is nil.”