What If? (11 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

- 1

Th

ough not necessarily those plugged into a second device. If a charger is connected to something, like a smartphone or laptop, power can be flowing from the wall through the charger into the device.

- 2

Note: If you’re ever trapped with me in a burning building, and I suggest an idea for how

we could escape the situation, it’s probably best to ignore me.

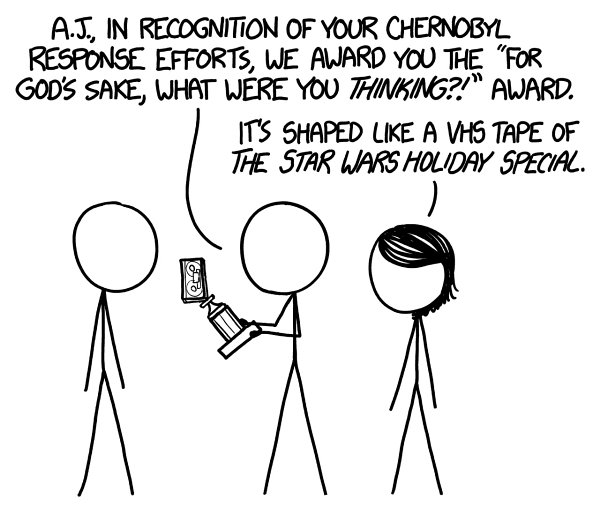

weird (and worrying) questions from the what if? INBOX, #2

Q.

Would dumping anti-matter into the Chernobyl reactor when it was melting down stop the meltdown?

—AJ

Q.

Is it possible to cry so much

you dehydrate yourself?

—Karl Wildermuth

Th

e Last Human Light

Q.

If every human somehow simply disappeared from the face of the Earth, how long would it be before the last artificial light source would go out?

—Alan

A.

Th

ere would be a

lot of contenders for the “last light” title.

Th

e superb 2007 book

Th

e World Without Us,

by Alan Weisman, explored in great detail what would happen to Earth’s houses, roads, skyscrapers,

farms, and animals if humans suddenly vanished. A 2008 TV series called

Life After People

investigated the same premise. However, neither of them answered this particular question.

We’ll start with the obvious: Most lights wouldn’t last long, because the major power grids would go down relatively fast. Fossil fuel plants, which supply the vast majority of the world’s electricity, require a

steady supply of fuel, and their supply chains do involve humans making decisions.

Without people, there would be less demand for power, but our thermostats would still be running. As coal and oil plants started shutting down in the first few hours, other plants would need to take up the slack.

Th

is kind of situation is difficult to handle even

with

human guidance.

Th

e result would be a rapid series of cascade failures, leading to a blackout of all the major

power grids.

However, plenty of electricity comes from sources not tied to the major power grids. Let’s take a look at a few of those, and when each one might turn off.

Diesel generators

Many remote communities, like those on far-flung islands, get their power from diesel generators.

Th

ese can continue to operate until they run out of fuel, which in most cases could be anywhere from

days to months.

Geothermal plants

Generating stations that don’t need a human-provided fuel supply would be in better shape. Geothermal plants, which are powered by the Earth’s internal heat, can run for some time without human intervention.

According to the maintenance manual for the Svartsengi Island geothermal plant in Iceland, every six months the operators must change the gearbox

oil and regrease all electric motors and couplings. Without humans to perform these sorts of maintenance procedures, some plants might run for a few years, but they’d all succumb to corrosion eventually.

Wind turbines

People relying on wind power would be in better shape than most. Turbines are designed so that they don’t need constant maintenance, for the simple reason that there are

a lot of them and they’re a pain to climb.

Some windmills can run for a long time without human intervention.

Th

e Gedser Wind Turbine in Denmark was installed in the late 1950s, and generated power for 11 years without maintenance. Modern turbines are typically rated to run for 30,000 hours (three years) without servicing, and there are no doubt some that would run for decades. One of them

would no doubt have at least a status

LED

in it somewhere.

Eventually, most of the wind turbines would be stopped by the same thing that would destroy the geothermal plants:

Th

eir gearboxes would seize up.

Hydroelectric dams

Generators that convert falling water into electricity will keep working for quite a while.

Th

e History Channel show

Life After People

spoke with an operator at

the Hoover Dam, who said that if everyone walked out, the facility would continue to run on autopilot for several years.

Th

e dam would probably succumb to either clogged intakes or the same kind of mechanical failure that would hit the wind turbines and geothermal plants.

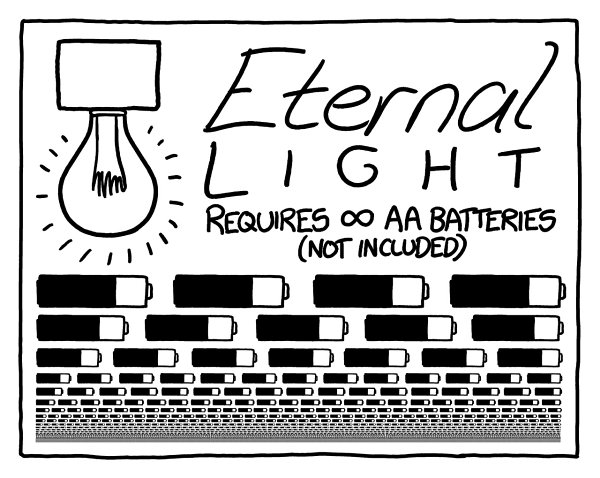

Batteries

Battery-powered lights will all be off in a decade or two. Even without anything using their power, batteries

gradually self-discharge. Some types last longer than others, but even batteries advertised as having long shelf lives typically hold their charge only for a decade or two.

Th

ere are a few exceptions. In the Clarendon Library at Oxford University sits a battery-powered bell that has been ringing since the year 1840.

Th

e bell “rings” so quietly it’s almost inaudible, using only a tiny amount of charge with every motion of the clapper. Nobody knows exactly what kind of batteries it uses because nobody wants to take it apart to figure it out.

Sadly, there’s no light hooked up to it.

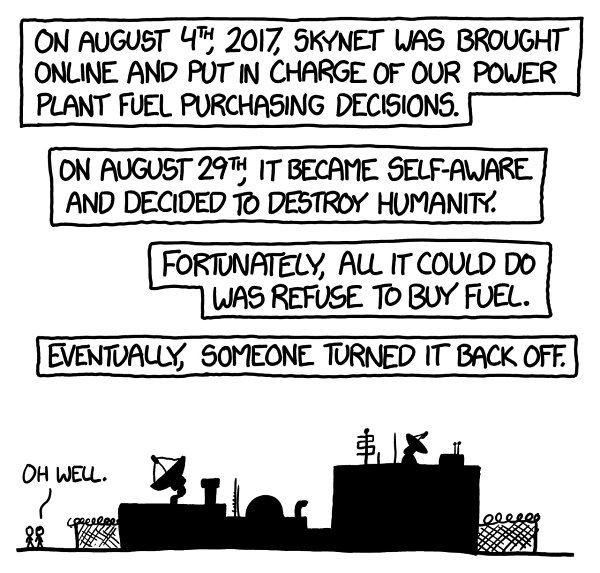

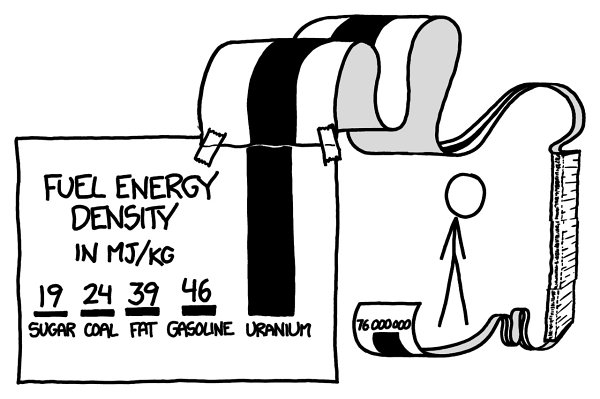

Nuclear reactors

Nuclear reactors are a little tricky. If they settle into low-power mode, they can continue running almost indefinitely; the energy density of their fuel is just that high. As a certain webcomic put it:

Unfortunately, although there’s enough fuel, the reactors wouldn’t keep running for long. As soon as something went wrong, the core would go into automatic shutdown.

Th

is would happen quickly; many things can trigger it, but the most likely culprit would be a loss of external power.

It may seem strange that a power plant would require external power to run, but every part of

a nuclear reactor’s control system is designed so that a failure causes it to rapidly shut down, or “

SCRAM

.”

1

When outside power is lost, either because the outside power plant shuts down or the on-site backup generators run out of fuel, the reactor would

SCRAM

.

Space probes

Out of all human artifacts, our spacecraft might be the longest-lasting. Some of their orbits will last for millions

of years, although their electrical power typically won’t.

Within centuries, our Mars rovers will be buried by dust. By then, many of our satellites will have fallen back to Earth as their orbits decayed. GPS satellites, in distant orbits, will last longer, but in time, even the most stable orbits will be disrupted by the Moon and Sun.

Many spacecraft are powered by solar panels, and others

by radioactive decay.

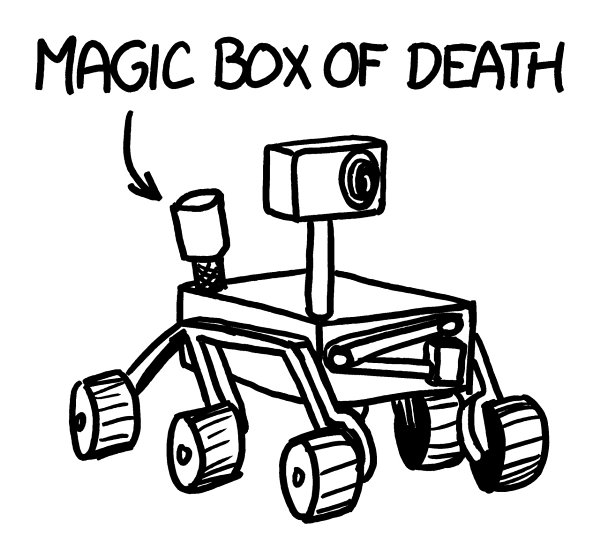

Th

e Mars rover

Curiosity

, for example, is powered by the heat from a chunk of plutonium it carries in a container on the end of a stick.

Curiosity

could continue receiving electrical power from the RTG for over a century. Eventually the voltage will drop too low to keep the rover operating, but other parts will probably wear out before that happens.

So

Curiosity

looks promising.

Th

ere’s one problem: no lights.

Curiosity

has

lights; it uses them to illuminate samples and perform spectroscopy. However, these

lights are turned on only when it’s taking measurements. With no human instructions, it will have no reason to turn them on.

Unless they have humans on board, spacecraft don’t need a lot of lights.

Th

e

Galileo

probe, which explored Jupiter in the 1990s, had several

LED

s in the mechanism of its flight data recorder. Since they emitted infrared rather than visible light, calling them “lights”

is a stretch

—

and in any case,

Galileo

was deliberately crashed into Jupiter in 2003.

2

Other satellites carry

LED

s. Some

GPS

satellites use, for example,

UV

LED

s to control charge buildup in some of their equipment, and they’re powered by solar panels; in theory they can keep running as long as the Sun is shining. Unfortunately, most won’t even last as long as

Curiosity

; eventually, they’ll

succumb to space debris impacts.

But solar panels aren’t used just in space.

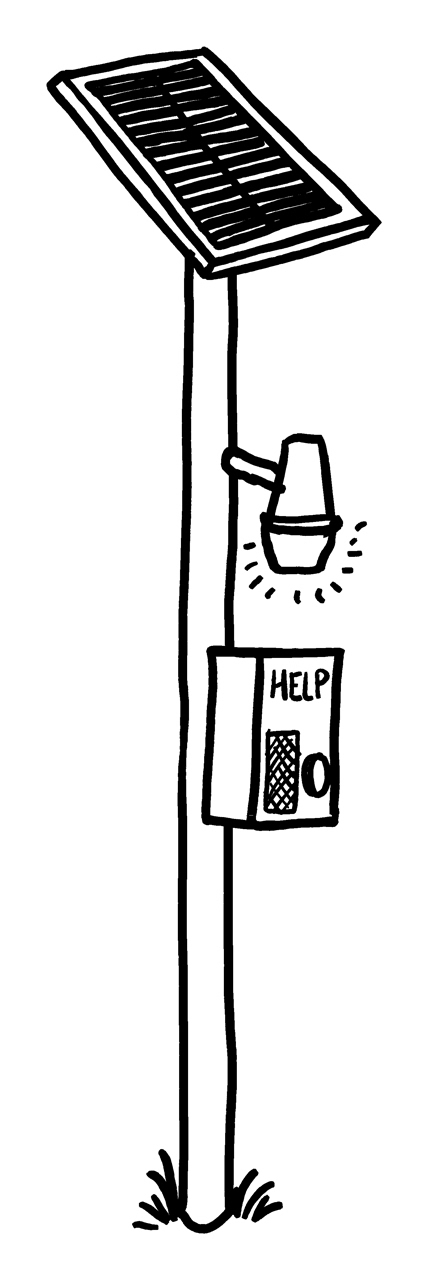

Solar power

Emergency call boxes, often found along the side of the road in remote locations, are frequently solar-powered.

Th

ey usually have lights on them, which provide illumination every night.

Like wind turbines, they’re hard to service, so they’re built to last for a long time. As long as they’re kept free of dust and debris, solar panels will generally last as long as the electronics connected to them.