Wheel of Stars (3 page)

Authors: Andre Norton

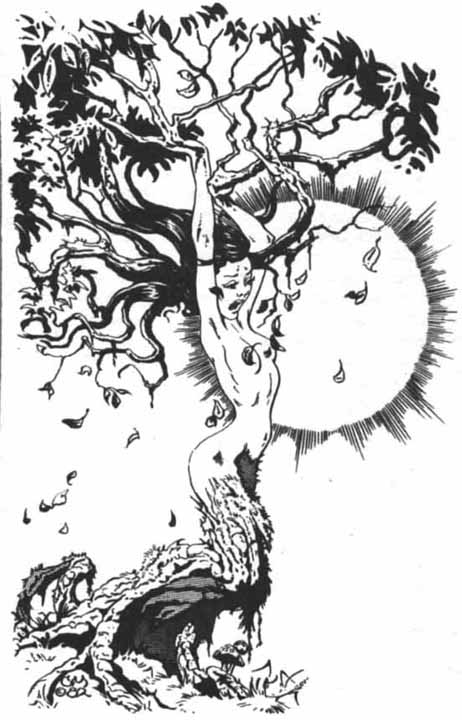

The whole was in soft color, the leaves green with a faint sheen of gold at their edging, while the body, in its most human part, was wholly of that precious metal yet with a ruddiness added. The tiny eyes in the female’s oval face were open, and some trick of the niche light caught a glint there, gem-hard in brilliancy—while the features of her near-human countenance held an expression mingling wild ecstacy with age-old sadness.

Gwennan stared, caught by all the imagination which she had so suppressed through the years from childhood. To her—though it was undoubtedly done by some trick of the clever lighting—there was a suggestion that those leaves trembled, that there was a faint rippling of the hair. It was as if she looked through a window or peephole into another world where abode forms of life far removed from all which she knew, yet in its way life which was permanent and intelligent.

“Ah, so you like Myrrah?” That question broke the spell the figure had laid on her. Gwennan blinked, flushed. She had allowed her naivete to show—which was irritating and she disliked him the more for reading her so quickly, for his subtle mockery at her open wonder. There was something in him which she continued to sense as vaguely wrong, slanted, which, in a way she did not understand, threatened her. But she was not able yet to define her emotions. Rather she shied from this unusual probing which part of her mind appeared to want to do.

“Myrrah?” She made a question of that name.

“Fair daughter of trees—what men once called a nymph.” Tor Lyle turned his attention apparently wholly to the figurine, for which Gwennan was glad. “A fine piece of work, is it not? We do not even know the artist. However, viewing it one can believe those old legends that once even trees possessed souls (if one might term them that) and could manifest another identity at will. You have viewed Myrrah—now come and tell me what you think of Nikon. They may not have been modeled by the same artist—but there is a kind of likeness in technique—yes, there is a decided likeness.”

She followed him to the next niche. There was a second figure, not this time half rooted in a massive trunk of wood. Instead its lower limbs were well apart, bisected in an entirely human fashion. Only where the feet might have been there were elongated appendages—toeless—resembling broad flippers. The skin was silver in hue and the concealed light skillfully revealed tiny overlapping scale which clothed it. It leaned a little forward, its arms outstretched in a curve as if to embrace something. Those slender arms ended in paws from which extended huge claws, cruelly displayed as if preparing to rend what the creature strove so to reach. To add to the impression of menace, the head was also hunched between the wide shoulders and the whole impression was one of avid desire to attack.

The head was a troubling mingling of caricature of human and simian. There was no hair, but rather a ragged crest of skin running from the mid point of the low forehead to the nape of the neck, standing erect. Those eyes were bulbous,

the nose flat, with only a hole to mark its position. While the slightly gaping mouth, above a nearly chinless jaw, was open to show white points of teeth which gathered and reflected the light with unwholesome clarity. It was monstrous, a nightmare thing, alien as the nymph, but wholly evil in its aspect.

“Nikon,” again Gwennan repeated the name. She frowned, trying not to look too closely, even though it drew her. If these were legendary creatures of mythology it was a series of legends new to her. She recognized neither name.

“Yes,” once more mockery was in his voice. The girl half expected him to break into laughter at her ignorance. “Now there is—”

“Miss Daggert—” The cool, yet welcome sound of her own name was like a small, clean breeze in that dark place. It banished the influence she was half aware Tor Lyle could exert at will.

Gwenan turned, relieved, on the verge of a small new happiness, to greet her hostess.

As the young man, who now actually appeared a little diminished in his glitter, the mistress of the house wore a long velvet gown. The robe-like garment was simply cut, without any ornamentation. Still it added to her stature—almost having the character of the classic garb of a priestess far removed from the world in which Gwennan moved—the world which lay outside these thick walls around her now.

It was grey and caught in about her waist by a twisted cord of tarnished silver. Around Lady Lyle’s neck a chain of the same dulled metal supported a disc surmounted by the upturned horns

of a crescent—both lacking the intricate embellishment which complicated the pattern of a sun disc worn by Tor.

“So—” she glanced beyond Gwennan now at her young kinsman. The girl who had never considered herself particularly observant, nor attuned to others’ moods, was aware of a strain. As if, between these two, there was discord which could only be feebly sensed, perhaps never open to such action as she herself might understand.

Now Tor appeared to yield ground willingly, though Gwennan was still convinced that the mockery had not vanished from either his eyes or the curve of his mouth. He stepped back, allowed Lady Lyle to sweep the girl with her into an adjoining room. Biding his time—why had that particular thought crossed her mind now? Gwennan had only an instant or so to question before she became the willing guest — the ensorcelled visitor.

For ensorcelled she was, dazzled, charmed as never before. They dined, Lady Lyle at the head of a dark, old table, seated in a chair with a tall carven back, seeming more and more to wear the guise of a queen enthroned. Gwennan felt lost in a similar chair, her fingers now and then slipping along its arms, aware of the twisting of carvings she did not have a chance to see plainly.

Tor Lyle was opposite her across that spread of wood on which crystal and fragile china, silver, cobweb lace and linen made islands. Nor did he once break into the conversation which Lady Lyle maintained, though he drank constantly from a tall stemmed goblet, small sips of an amber-colored

wine, which Gwennan had tactfully refused. From Miss Nessa’s household all such indulgences had been banished and she mistrusted her own reaction to that particular offering.

At her refusal Lady Lyle had nodded, almost as if she had approved and Gwennan noted gratefully that she herself had riot allowed her own waiting goblet to be filled.

No, Tor Lyle did not speak. His eyes, a little narrowed as they had been at their first meeting by the mound, went from Gwennan to Lady Lyle and back again. He might be a man confronted by some puzzle which it was very necessary that he solve.

Having finished their meal, the mistress of the house once more led the way into another room, again wall-panelled. The wood had been painted, and the colors were freshly bright as if age had never touched. A brush, wet-tipped, might just have been raised from a last curve. There were figures pictured, which were wholly human, behind them the rise of cities and towns—some drawn with that lack of perspective which had never troubled artists of the past. They seemed to flow from one stretch of wall to the next, and Gwennan guessed that all were meant to follow the thread of some story, for she marked one of the same figures in action from one panel to another.

Only she was not given any time to study this, for what Lady Lyle promptly laid out on another table were very modern photographs. These looked starkly bare when one had seen the walls.

At a glance Gwennan recognized the places which had been so filmed. Three were of rocks which she had noted on her own one short trip of exploration.

Lady Lyle nodded, studying the girl’s face closely.

“Yes,” her voice was eager, alive. “These are what we should seek. See, these lie directly on a path which is laid so—” With an impatient whisk of the hand she brushed the pictures to one side, producing a map on which was drawn a scarlet line, so deeply red as to seem alive. Still the rest of the map was brown with age, other lines on it much faded. Gwennan had to peer very closely to make out a few landmarks she recognized. This was certainly a section of the valley—but one which showed nothing of dwellings and farms with which she was familiar.

“Drawn so,” her hostess was continuing. “It intersects with another from the north—”

Yes, there was a second line, again much faded, its color a palish pink.

“And so you see where is their intersection? It lies at the stones—the meadow stones!”

“I never looked to the north.” Gwennan dared to put out a finger tip to trace that other, much older, faded line. “These marks—” surely those dots were not age spots but had been set there for a purpose—"they are also stones?”

“At this hill notch there is a triangular rock. It is mounted to point so—” Now it was Lady Lyle’s finger which stabbed down at the old map. “It is supported upon three small stones and the balance is correct. Let your experts who talk of

glacier deposits make what they can of that!”

“Leys—” Gwennan’s interest was caught now. “And where they intersect—”

“Places of added force! Just so. There are such sites—much greater perhaps. Stonehenge is one, Canterbury with all its legends as a sacred place. Even more—Glastonbury. All these mark interceptions of the leys. This one is but a simple conjunction compared to those. The leys are lines of magnetic force—that is already halfway proven—or relearned. Eventually those who have argued this truth for years will be vindicated. Once, we believe, men and women knew how to summon such forces, to harness them. They controlled powers of which men today cannot begin to conceive.” Her words came faster and faster, her pale face showed a small flush as if blood gathered there in proof of her earnest belief in what she said. “Lost—” her hand no longer moved across the map, but lay limply, palm down upon its edge. She drew back a little in her chair, her eyes closed, and she breathed quickly, short panting breaths.

Gwennan was on her feet, alarmed, reaching for those limp hands, grasping their chill flesh quickly. It was plain that Lady Lyle was ill. She looked beyond the half-fainting woman to where Tor Lyle had lounged, taking no part in their inspection of the map. Nor did he move now—even when it was so apparent that his kinswoman needed help.

“She is ill! Dr. Hughes should be called!”

The young man shook his head. That smile was back, shadowy about his lips, and his eyes remained

half veiled. She longed to shout at him.

When he got to his feet it was not to come to the woman whose labored breathing was now harsh in the room. Rather he went to pull a cord which hung near the huge fireplace. Lady Lyle stirred a little, opened her eyes to look straight into Gwennan’s. There was no color in her face, while in the girl’s hold her two hands were colder, seemingly more limp. The older woman drew a deeper breath—then another. She smiled, a small ghost of her earlier welcoming smile.

“Did I alarm you, child? This is nothing. When one has lived as long as I, sometimes even a small indulgence in excitement brings its toll. Do not worry—I shall quickly be myself again—”

Gwennan released her hands as one of the dark, silent serving women entered. She placed before her mistress on the table a tray bearing a single cup—one which appeared fashioned from a curved horn, so small that the beast from which it had been taken could not have been larger than a cat. Lady Lyle put forth her hand slowly, picked up the unusual cup and drank its contents. When she put it down empty she sat up with energy, looking fully alive and able again.

A wild crack of thunder sounding directly overhead sent Gwennan cowering among the bed covers. Outside the window a flash of lightning followed. Then came another sound not unlike an explosion. That bolt must have struck some tree not too far away. Again thunder rolled.

Only it was not the fury of the storm which had awakened her. She had come instantly out of sleep, as if summoned by a call. Just as it was more than thunder and lightning for which she listened—or tried not to listen—now.

She swallowed. A stronger sense of fear than she had ever known kept her taut and tense. Fighting against rigid terror, Gwennan was able at last to move, to sit up in the midst of her tangle of covering, to reach out to switch on the bed lamp—fervently thankful when it worked. She feared that storm damage might have left her in the dark.

Rain beat against the walls. She sat, shoulders hunched, still listening, pulling the upper quilt shawlwise around her. It was very cold. In the fall she always closed off the upper rooms of the old house, moving into the small downstairs bedroom which shared a wall with the kitchen.

Lightning—another crash of thunder. There was something else—for which she could not find words. Gwennan slipped from the edge of the bed, not pausing to put on her waiting scuffs, padded across the rag carpeting towards the bathroom, her guide the faint glow of the night light there. As she switched on a second lamp, there came another fierce roll of thunder.

Water flowed as she filled the drinking glass, looked at the mirror above the washbasin. Her hair hung in limp, sweaty strands. The flesh of her face looked both puffy and unusually pale. Gwennan drank and wondered if now, when she was so thoroughly awake, it might not be well to heat some milk.

Bad dreams. It must have been the building, the breaking of this storm which had given her the one from which she had so suddenly roused. She could not remember any details now. Only that she had awakened gasping, her nightgown sweat-dampened, her body aching. Her heart still beat fast, and all the rationalizing she tried to summon could not banish the remains of pure terror.

Fear—of what? She had known such storms all her life—though this one was late in the year. Suddenly she gripped the edge of the washbasin, holding to it tightly as an unexpected dizziness struck her. The sensation went as quickly as it had come, but left her weak and unsteady—and more afraid.

“There is nothing wrong—” she told herself, trying to speak calmly. “Just a storm—There is nothing wrong!”

Steadying herself with one hand against the wall, fearful of a return of that strange giddiness, she made her way back to the bedroom. But not to bed. Instead she stood just within the circle of light thrown by the reading lamp, staring about her at all the familiar things which loomed half in, half out of the shadows. There were her clothes laid out on a chair, ready for morning—the book she had nodded herself to sleep over—her small clock, its hands pointing to the hour, just hard on three.

Nothing was out of place, nothing different from what it was every night of the winter season while she used this room. Why should there be? Now she settled herself on the edge of the bed, pulled absently at the covers about her.

Fancies—not to be trusted. She had deliberately allowed too much to stimulate her imagination lately. Gwennan jerked up a pillow to support her back, unable as yet to lie down, having no desire to turn out the lamp. The book—perhaps if she read for awhile—

Only a part of her mind was too alert, had already turned in another direction. She was thinking of the acquaintanceship which had begun so abruptly and in its way altered the stolid round of her existence. Her first visit to Lyle House had not been the last, and each time she went there it was like being drawn deeper into enchantment.

For some reason Lady Lyle had fostered a relationship

which surprised Gwennan. What had the girl to offer in return which would be of any interest to a woman whose world was so far removed from hers—so utterly alien to everything Gwennan had ever known?

A village girl of very limited formal education—one without any claim to easy manners, certainly nothing beyond the very ordinary. It would appear to anyone that Lady Lyle would consider her the last person to cultivate. Looking back now, Gwennan could hardly believe that it had been only three weeks since she had first walked into the treasurehouse the Lyles had so long made their headquarters. She had seen much there since, marveled at all those grey stone walls sheltered. Each room she had been invited to enter had been a new revelation—such as the library with more ancient maps, older books—even illuminated parchments which had been freely unrolled for her to marvel over—volumes so old that they had been fastened with locks of rust-pitted iron or tarnished silver. A drawing room with glass walled cases, chests, cabinets—holding great and small rarities so crowded together that it was difficult to distinguish one from the other. She had been fascinated, completely captivated—yes—enchanted in the old sense of that word.

Though in fact she had never been given much time to do more than attend to Lady Lyle herself, her attention claimed fully by her hostess every time she passed through that fortress-like doorway. She answered questions, was skillfully drawn out to talk. It was never until she was once

more free of that house that she even realized how skillfully and fully details of her life had been confided to Lady Lyle, and how very little of her hostess she ever learned in return.

There had been questions about her parents—and for those she had had little straight answers. Miss Nessa, as Gwennan had early learned, had possessed very little liking for the man her much younger sister had married. He was a footloose wanderer Miss Nessa had insisted in a few rare outbursts. That he and his wife had died in the far southwest on their way to some foolish piece of desert exploration was no more than was to be expected. She had done her duty in accepting the child of that misalliance and making very sure that Gwennan was not encouraged in any ways which approached such shiftlessness.

From that patchy knowledge of her own origin, Gwennan had been led, by astute and compelling conversation, to enlarge on her private interests. Finding for the first time someone who shared, or seemed to, her secret and timid attempts to learn things which no one in the village would understand, Gwennan talked and talked—sometimes, she was sure afterwards, uncomfortable with a sense of shame, far too much—being too assertive. It was as if when she was with the mistress of Lyle House she was being offered a key which would unlock a door she had long sought.

Luckily, for she still distrusted and disliked him, Tor Lyle was not there. He had vanished without any explanation on his kinswoman’s part shortly after Gwennan’s first visit. Probably he had departed on one of those journeys to which

men of his blood were so addicted. Lady Lyle appeared in no way to miss him.

Tor Lyle. Gwennan slid down farther on her pillow support—she knew she had no talent for social graces. Everytime she had met him she had been more and more painfully aware of her failing. Not only that she was physically plain, overgrown, awkward, a nonentity, but he mocked her silently. She was also very sure that he disliked his aunt’s continued interest in her. However, it was also plain that Lady Lyle was ruler in that household and only her desires were of importance.

So—well, even if it ended tomorrow and Lady Lyle would be gone also, she had had this much—so much to think about. She was—

Gwennan stiffened, sat tense, one hand going to her mouth, her eyes wide. The storm had blown itself away to a distant muttering now. But the window was still tightly closed. Then how could she hear that—a strange shuffling as if feet never quite lifted from the ground broke into those branches so carefully banked just last week about the foundations of the house as insulation against the winter—the generations-old system the village followed from fall until spring. She turned her head slowly. Fear was with her again—stronger—weakening—flooding her mind, affecting even her body. The window—a square of dim light—

There—

Gwennan could not move, to draw the shallowest of breaths was an effort. She learned then that there is a terror so great that the edges of it

mercifully cloud the mind. Maybe she actually blacked out for a moment—she could never afterwards be sure. Slowly she became conscious of her sweating body rigid and chill, her hands gripping the edge of the quilt so tightly that her fingers ached.

Red—red

eyes!

Yes—she was sure of the eyes. The head in which they were set—that remained only a hazy, darkish mass. But those eyes—like the coals of a hearth fire blazing steadily—fastened on

her.

She shivered, her body yielding to the ice of pure terror. Horror—a hatred so raw it was never meant for any human being to front, that—all of that—was in those flame eyes!

This was no dream. Out there in the night hunched something which was not of a normal world. Bears had been reported seen in the woodlands—even a cougar had been sighted last year—This was no animal—it was more—apart from anything she knew—or could sanely believe in.

Gwennan uttered a small sound, close to a moan. The unknown creature was watching her—it must be—she was fully exposed to sight by the light of the lamp. She listened for more crackling of the foundation brush, for the sound of splintering glass as it broke its way in to her. That—that thing was a hater. She had no doubt of that.

How long Gwennan huddled there waiting for attack to follow she did not know. At first she could not even move, the threat of the eyes held her motionless. Then, making the greatest effort she had ever known in her life, she started to crawl down the other side of the bed, as far as she

might get from the window. Afraid to try to stand lest her legs buckle under her, she reached one of the bedposts, clung to it.

The telephone—help—She tried to think, as, with a second great surge of effort, she made herself look away from the window. To reach the phone she would have to get across the short hall, into the kitchen which was also, country-fashion, the sitting room.

Gwennan crumpled forward, on hands and knees now. She put all her strength into crawling across the cold floor, winning inches at a time. Then the darkness of the hall enfolded her. She had to heave herself up to claw at the latch of the kitchen door before she could fall through into that other room, still warmed by a well-banked wood fire.

Sobbing for breath, she used the edge of the much worn old sofa as a support, lurched from that to the chair by the small window table. Collapsing into that, her hands shook so she could not at once drag the phone to her. Nor could she at first discipline her fingers to dial—making three vain tries before she managed in the dark the combination which meant an emergency call.

“Sure was somethin’ out there all right, Gwen—smashed all those branches under the window flatter’n a wheat cake. No rain did that, and I never heard of no bear comin’ this far into town—not in years anyhow.” Deputy Hawes leaned against the table while Gwennan poured a second brimming mug of coffee. “Trouble is the ground’s

just too hard hereabouts since that last frost—even after the rain—to show us a good print. Sam is goin’ to bring over the dogs come sunup. What gets me is that stink—never smelled anything to match it before. ‘Nough to churn a man’s insides crossways, that is. Never heard as bears stunk like that—worse’n any skunk as got his dander up. You know, Gwen, t’aint safe maybe you livin’ here all alone. Kinda cut off, too. The Newton place is a good bit away and there’s that there big hedge between you, cuttin’ off a good sight of your place. You can’t even see their house—” He gestured at the window where the gray light of morning showed now.

“An’ if we’ve got a bear roamin’ around—”

Gwennan pulled her flannel robe tighter about her throat. She had made a great effort and regained outward control before Ed Hawes had arrived. At least he had not seen her near-reduced to idiocy as she had been earlier. He was two years older, but they had ridden together on the school bus to the high school at the center. Ed Hawes did not possess much in the way of imagination as she well knew, but perhaps that was a quality one was better off without in the present instance.

She had been most careful in her report. The red eyes—yes—but she had kept quiet about the abject terror those had awakened in her and the feeling of utter evil which she had afterwards recognized as part of that fear. Now she was thankful that there did remain physical traces of the prowler and she had not been wrong in calling for aid against something which was not

— Not what? Gwennan refused to allow herself to follow that train of thought.

“Why would a bear look into a window?” she wondered aloud.

“Well, now, that maybe ain’t as queer as you’d think, Gwen. Some bears are curious. I heard of one two summers ago that prowled around a camp up near Scott’s woods—gave a tourist a scare when he poked his head in to watch her dress just as calm as you please. Could be it was attracted by your light and just took a look-see. Sam’s hounds, they’ll pick up its trail—They are smart dogs. Mighty good coffee, Gwen, I’m obliged. Got to call in from the car now. I’ll wait around for Sam—gettin’ so much lighter now maybe I can see somethin’ more myself. That stink—that’s what really gets me. Bears maybe ain’t rose bushes but they don’t never smell

that

bad!”