White and Other Tales of Ruin (21 page)

Read White and Other Tales of Ruin Online

Authors: Tim Lebbon

She was in her garden again, stubbornly wheeling herself between fruit bushes, plucking those that were ripe, cleaning the others of the greasy dust that hung constantly in the atmosphere. I was following on behind her, bagging the fruit and wondering what she was going to do with so much. There were only so many pies she could make.

“

I can’t see how any good has come of the Ruin. Millions have died. The world’s gone to pot.” I thought of the marks on my chest, slowly growing and expanding. I had still not told her. “Millions more are going to die.”

She looked up at me from her wheelchair. “If you see no good in the Ruin, it’s ‘cause you’re not meant to. Me, I see plenty of good in it.”

“

What? What good?”

Della sighed. I wanted to hold her, comfort her, protect her. But I knew I never could. “Look at all that,” she said, indicating the basket of fruit I carried. “I’ll never use all that. A few pies, a tart, a fruit salad. All that’s left will turn brown, decay, collapse in on itself. Then I’ll spread it on the ground and it’ll give new life to the seedlings I plant next year. New from old. Good fruit from bad flesh.” She took a bite from a strawberry, cringed and threw it to the ground. “So, in years to come, when all the mess of the Ruin has cleared up or rotted down, the world’s going to be a much safer place.”

I did not understand what she meant. I still do not understand now. But I like to think she was right.

ii

We arrive back in the town and make straight for the harbour. There is a ship at anchor there, a large transport with paint peeling from its superstructure and no visible emblem or flag of any kind.

“

Pirates?” I guess.

“

That’s all there are nowadays, I suppose.” Jade has become quiet, withdrawn, but I am uncertain as to the cause. We made the journey from String’s in one go, travelling through the night and keeping a close look-out for roaming gangs of bandits. I’m still not sure whether I believe the cannibal yarn Jade spun when I first arrived here, but I kept my eyes wide open on the way down. Wide, wide open.

I wasn’t about to be eaten after receiving a miracle cure.

“

I suppose I could find out where it’s heading.”

“

Good idea,” she says. “I’ll try to get us some food.”

There is a subject that we are both skirting around, though I can tell by the air of discomfort that she is as aware of it as I: Where are we going, and are we going together?

iii

“

When you’ve got a tough decision to make, don’t beat around the bush. That’ll get nothing sorted, and it’s prevarication that’s partly responsible for the mess the world’s in. Remember years ago, all the talk and good intentions? Farting around, talking about disarmament and cleaning up the atmosphere and helping the environment, while all the time the planet’s getting ready to self-destruct under our feet.”

Della threw another log on the fire, popped the top from a bottle with her teeth and passed it to me, laughing as it foamed over the lip and splashed across her old carpet. It was an Axminster. I wondered what it was like in Axminster now, how many people were living in the carpet factory, whether it was even still there.

“

Take that Jade. Now, whatever it is she wants she’s already made up her mind, she’s that type of woman. So why piss around when time’s getting on? Ask her what’s up, tell her what you’re up to. That’ll solve everything.”

She scratched at her stump, drawing blood. Not for the first time I wished I could write down everything she said, record it for future use. But somehow, I thought I’d remember it all the same.

“

If there’s a problem there, with you and Jade, it’ll be there whether you confront it now or in a week’s time. Pass me another chicken leg.”

I passed her the plate. She laughed at my retained sense of etiquette. “Manners maketh fuck-all now, Gabe. Faith maketh man. Just you remember.”

iv

I open my eyes, the remnants of a daydream fading away. I wonder how Della could have known about Jade all that time ago. I wonder how she could have known about String. I realise that, in both cases, it was impossible.

Faith maketh man. I certainly have faith. Whether it’s fed from somewhere or I make it myself, I possess it. And it possesses me.

I move away from the bench as I see a uniformed man come down the gangplank from the ship. There is a noisy crowd on the mole, trying to get a glimpse of what is being unloaded from the hold. A few men in army uniforms lounge around, cradling some very unconventional fire-arms. I guess they could wipe out the town within an hour or two with the hardware they’re displaying.

I approach the man, hoping the uniform is not a lie. “Could you tell me where this ship has come from? Where it’s going?”

He spins sharply, hand touching the gun at his belt, but his expression changes when he sees me. Perhaps he thinks I may have some money because I’m a European. I prepare to run when I have to disappoint him.

“

Came from Australia. Goes to Europe. Take you home, eh?” He rubs his fingers together and I back away, nodding.

“

Hope so.”

Jade is sitting on a wall near a row of looted, burnt shops. She has some fruit, and is surreptitiously nibbling at a chunk of pink meat.

“

How did you get that?”

She smiles. “Used my guiles and charm. Made promises I can’t keep. Just hope I never see him again.”

I frown. “Well, maybe it won’t matter.”

“

What do you mean?” she says, but I think she knows.

“

The ship’s going to Europe. Are you coming with me?” There, right out with it. No beating around the bush. No prevarication.

“

No,” she says. I feel myself slumping with sadness. She hands me some meat, but I do not feel hungry. “Have you got someone there?”

I look at her, thinking, trying to decide whether or not I have. “Not as such,” I say. “Not really. I don’t think so.”

“

And what does that mean?”

I shrug. “I’ve got faith in someone, but I don’t really think she exists.” If you know someone’s faith, you know their soul. I feel that Jade has always known my soul, and I think I may love her for that.

“

I can’t come, Gabe,” she says. “It’s not too bad here. I know a few people. I’ll survive.” She nibbled at some fruit, but I could tell that she was less hungry than me. “You could stay?”

“

You could come.”

We leave it at that.

v

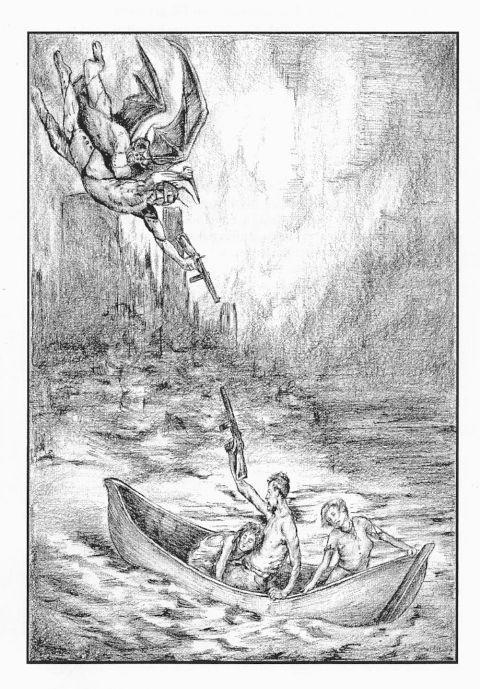

As I board the ship, a roll of Jade’s bribe money sweating in my fist, I hear a sound like a swarm of angry bees. I glance up and see the flash of sunlight reflecting from one of the Lord Ships. It is at least two miles out to sea, drifting slowly across the horizon, but it provokes the reaction I expect.

The whole harbour side drops to its knees. Soldiers go down too, but they are soon on their feet again, kicking at the worshipping masses, firing their guns indiscriminately into huddled bodies. I search the crowd for Jade, then look for the alley she had pulled me into on that first day. I see the smudge of her face in the shadows, raise my hand and wave. I think she waves back.

The ship remains at anchor long enough for me to see the bodies piling up.

* * *

Hell

“

May you live in interesting times.” — Anon

When she was thirteen, religion found Laura. She didn’t go looking for it, of that I was sure, but just as an insidious cancer had taken my wife seven years before, so religion stalked my lovely daughter and eventually stole her away. At least, that’s what I thought at the time. God is always so easy to blame.

She left in the night without saying goodbye.

The day before, we’d taken a trip to the local park. Laura wanted to find a suitable location for a photo shoot — she had dreams of becoming an actress and was slowly composing a most impressive portfolio — and I had a day owed to me at work, so we agreed to make an afternoon of it. I carried the picnic hamper and Laura nattered every step of the way, her non-stop chat and nervous laughter inherited from the mother she had barely had time to know. The hamper was heavy and the day was hot, we had jam tarts and cheese and cucumber sandwiches and bottles of beer for me and orangeade for Laura. She spoke of her hopes for the future, while my thoughts drifted to the past. I’d often come to the park with Janine, my wife, Laura’s mother. I smiled inside, a sort of comfortable melancholy that had all but replaced the raging grief. Then Laura tripped me and stole a bottle of beer from the spilled hamper, I ran after her and tackled her onto the grass, and the afternoon turned into one of those times you never forget, taking on a hue of perfection that cannot be eroded by the tides of time. For those few hours everything was faultless. Bad news was something that happened to unknown people in far-away lands. On the way home Laura hugged me and kissed my sunburned cheek, and she told me she loved me. And I knew that I’d be fine because in her voice I heard Janine. In her smile I saw my wife.

She left in the night without saying goodbye.

There was a note in her room to tell me why she’d gone. She’d scribbled it in a hurry as if afraid the dawn would find her out. It spoke of God and fear and faith and perfection and guilt and envy, and I thought she meant that she felt bad living as she did. But in truth, that note only went to confuse me more.

If only I’d known then that she had not even written it.

I tried to cope, I did my best, but in the end I went the only way I could to survive. I turned to Hell.

It had been a terrible six weeks since Laura had gone. I hadn’t heard a word from her, and although the police stressed that they were hunting high and low, they drew a blank. The International Police Force had been notified and her details had gone onto their database … although in a way I hoped I’d never hear from them. If I did, it may mean that her genetic fingerprint had been matched with that of a body pulled from the Volga in Moscow, or her dental records related to what was left of a car crash victim in France, a million possibles snicking and snacking through the organisation’s computers until

match

was found,

match

, a convergence of information that would mean a lifetime of misery for me instead of a vain, empty hope.

So they searched, and I searched, but all the while hope was slipping through my fingers. Whichever radical cult she’d hooked up with, they would have taken her far away from me. Already I would be little more than a vague memory in her mind, a confusing image of what a father should have been, an unbeliever, a waste. I sent out a plea over the net

there were groups that provided a search service, both electronically and, more expensively, physically

but even they admitted that the chances were slim. Most of the religious groups that had sprung up over the past decade eschewed technology, and it was already likely that Laura was essentially removed from existence.

All she’d have left would be herself, and whatever skewed faith she had found.

More than me, at least.

The route to Hell can only be found by those who need it the most. It is never advertised or discussed openly in public — there are no books about it, no documentaries — but just as the true reality of things is hidden beneath the manufactured patina of everyday life, so most people know about Hell. They know about it and believe in it, but they never honestly feel that they need it.

Things can never get

that

bad

, they think.

My life can’t drop to

those

depths, surely.

I went looking without knowing what I was looking for. I’m sure that’s how I discovered Hell so easily. I was wandering the streets one evening, listening out for anything that sounded like a religious meeting. There were many gatherings in the city, many religions, all of them right and all of them wrong, as ever. My walk took me along one street, down the next, across open shopping plazas and through a park. There were a lot of people around now that the sun had gone down, and all those I saw appeared to have somewhere to go. I was aimless, and I stuck out like a gorilla with blue hair. My face was slack, my eyes wide and demanding, my mouth moving silently, betraying my encroaching madness. Because I truly believed that’s where I was: at the edge of madness. Janine was seven years in her grave, her perfume as fresh in my nostrils as ever. And now Laura was gone, stolen from me by the perverted followers of some god that had never and could never existed, her mind probably taken from her, twice removed from me. My memories of her were beginning to feel unfair. They should have been

her

thoughts, not mine. It seemed so wrong that I should have more recollections of my daughter’s life than she, had the brainwashing gone as far as I feared.