White Bicycles (19 page)

Bob Squire, Beverley and John Martyn, Hastings, 1970

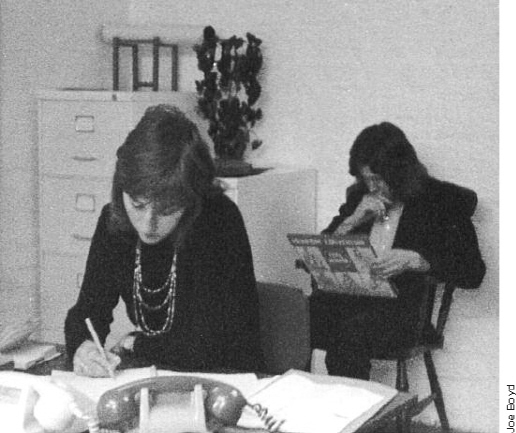

Marian Bain and Nick Drake, Witchseason office, 1970

Blue Notes, ICA, 1965: Dudu Pukwana, Mongezi Feza, Johnny Dyani, Chris McGregor

Incredible String Band on tour, 1969: Joe Boyd, Rose Simpson, Mike Heron, Christina McKechnie and Walter Gundy

Linda Peters (later Thompson), 1971

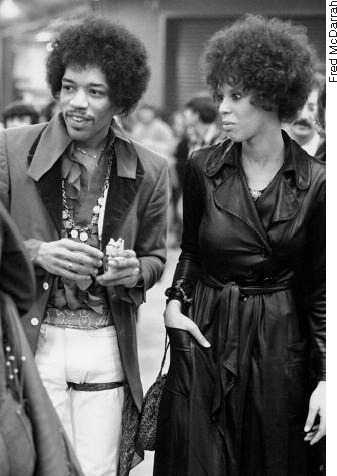

Jimi Hendrix and Devon Wilson, New York, 1970

Fairport Convention, rehearsals for Liege and Lief: Ashley Hutchins, Dave Swarbrick, Sandy Denny, Richard Thompson, Simon Nicol, Dave Mattacks

Jenner rang the next day to say that Morrison had looked over the Polydor/Witchseason contract, found it wanting and proposed a Plan B. His agency would put up the money to record the single, then shop it to EMI or Decca as a finished master. Based on what he had heard in the studio, he was certain they could get a £5,000 advance for it. They wanted me to produce it, but as the Floyd’s employee, rather than the other way around. After kicking the wall a few times and cursing, I rang back and said I would agree so long as I was guaranteed the right to produce the first album. Bryan said he understood my feelings but was concerned that EMI wouldn’t like having their hands tied and we’d just have to play it by ear. For a couple of days I held out, then buckled, naïvely assuming that if the record was a hit, it would be in everyone’s interest to keep a winning team together.

In early February we went into Sound Techniques, where we recorded and mixed ‘Arnold Layne’ and the B-side, ‘Candy And A Currant Bun’, over two nights. I liked the Floyd and the atmosphere was good. Even with a four-track machine, the mix was tricky. These days computers remember every movement of the faders so you can get the balance on one section just right, then go on to the next part. In ’67, mixes were like recording takes; you had to get it in one pass or go back to the top and start again. While engineer John Wood and I controlled most of the balances, Roger leaned over my shoulder extending his big index finger on one of the faders to ensure that the surge of volume at the start of Rick’s organ solo was just right. It was a nice team effort and we all felt good about the results.

As Bryan predicted, EMI loved the single and offered £5,000 to sign the group. The royalty rate was far lower than Polydor’s, but the group needed the cash to buy a van. On the subject of producer, EMI stood firm. They wanted the group to use Abbey Road Studios and their staff man, Norman Smith, who had just had a novelty hit as a recording artist with ‘I Was Kaiser Bill’s Batman’. We had one final session together when Peter Whitehead filmed the band recording ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ at Sound Techniques as part of the

Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London

documentary. The result is probably the closest you can get to hearing what the original Pink Floyd sounded like live.

I went to the launch party for the single and wistfully wished them well. Witchseason Productions would have to get along without the Floyd. ‘Arnold Layne’ got into the Top Twenty despite a BBC ban for ‘indecent lyrics’. Norman Smith produced

The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn

, but John Wood and I were gratified that they had to come back to Sound Techniques to get the ‘“Arnold Layne” sound’ for the second single.

One evening in May I ran into Syd and his girlfriend in Cambridge Circus. It is strange to recall that early on a weekday evening there was almost no traffic in the heart of London. Syd was sprawled on the kerb, his velvet trousers torn and dirty, his eyes crazed. Lindsey told me he’d been taking acid for a week. A few weeks later Floyd fans were lined up three deep along Tottenham Court Road for their return to UFO. There was no artists’ entrance, so one by one they squeezed between me and the crowd, heading for the tiny dressing room in the back. I had exchanged pleasantries with the first three when Syd emerged from the crush. His sparkling eyes had always been his most attrac- tive feature but that night they were vacant, as if someone had reached inside his head and turned off a switch. During their set he hardly sang, standing motionless for long passages, arms by his sides, staring into space. Dave Gilmour was added to the group soon afterwards to cover for him and by the end of the year Syd was gone.

I remember the UFO crowd sitting on the wooden dance floor in front of the stage, completely engrossed as the Floyd played those early gigs. Pete Townshend came down one evening and spent the whole night at the right-hand corner of the stage by Roger’s amp, tripping on something. When I came by, he pointed at Roger’s open mouth and told me it was going to swallow him. There were many pilgrimages to those shows: Hendrix, Christine Keeler and Paul McCartney on the same night (but not together), German TV shooting UFO’s only surviving film clip. Hearing the descending opening chords of ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ takes me immediately back to those nights, when the lights would pulse and bubble against the stage, the crowd would cheer the familiar melody, the four of them would stare intently at their instruments and we would be off. The jaunty choruses of Syd’s songs were like fertile planets in a void of spaced-out improvisation: returning to the theme after a ten-minute excursion was both exhilarating and reassuring. Even today, with Syd’s era a dim memory and Roger off sulking on his own, there is something about a Pink Floyd song no one has ever been able to emulate.

Jenner and King were – like me – out of their depth once the Morrison Agency came on board and it was only a matter of time before they, too, would walk the plank. None of us imagined that decades later you could go to the remotest parts of the globe and find cassettes of

Dark Side

Of The Moon

rattling around in the glove compartments of third-world taxis along with Madonna and Michael Jackson. Pink Floyd’s success is difficult to analyse or explain. What they brought with them from Cambridge was all their own; London in 1967 just happened to fall in love with it first.

HOPPY AND I STARTED UFO because we were both broke. I had decided to stay in London and start my production company while Hoppy had given up his career as a photographer to launch the

International Times

. Neither venture was likely to yield much cash in a hurry.

We spent an early afternoon in December 1966 speeding around London in the purple Mini, looking at derelict cinemas and nightclubs fallen on hard times. (In those days, you

could

speed around London on a weekday afternoon.) Our last stop was a Tottenham Court Road basement next to the Berkeley and the Continentale cinemas (all now buried under concrete) with a small sign outside reading THE BLARNEY CLUB. A wide stairway with faded red carpet bolted to cement steps led down to a gloomy, low-ceilinged ballroom with a tiny stage and a smooth wooden dance floor. To the left was a fluorescent-lit hallway opening on to a seedy bar area. The owner, Mr Gannon, was slinging around soft-drink crates, counting under his breath between puffs on a Woodbine. We enquired whether the club might be for rent on a weekend evening. ‘I suppose I could let you have a Friday night for fifteen pounds,’ he said, ‘but I’d have to sell the soft drinks.’ Since most of our customers were likely to suffer from dry-mouth syndrome or tight-throat syndrome and we knew nothing about the soft drinks business, we shook on the deal and booked the last two Fridays in December. Pink Floyd was engaged as the house band. We couldn’t decide between Night Tripper and UFO, so we put both on the flyers handed out in Portobello Road market the previous Saturday. We had no idea who would turn up that first night, 23 December 1966, but freaks came out of the woodwork from all over the city and we made a profit. There was a general feeling of surprise and recognition; few had any idea there were so many kindred spirits.

Over the coming months, UFO introduced London to Pink Floyd, the Soft Machine, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, light shows, tripping en masse and silk-screened psychedelic fly-posters. We opened every Friday at 10.30 and closed around 6 a.m. when the Tube started running. Indica Books sold posters from the Fillmore and Family Dog ballrooms in San Francisco so we decided to create some of our own. My friend Nigel Waymouth was a partner in Granny Takes a Trip, King’s Road’s most extreme boutique, where they sold floral jackets and mattress-ticking suits and shirts with collars that drooped to the nipples. Nigel had painted their shop window in a post-Beardsley acid-dream style with the front end of a car protruding on to the pavement. I nominated him for the task of creating our first poster.