White Bicycles (21 page)

As UFO’s popularity grew, so did the conflict between me and the revolutionary vanguard who staffed it. Hoppy was the beloved leader whose heart was clearly on their side; I was the breadhead who cared only about his music business career. The majority of the UFO crowd just wanted to get high and laid and listen to great music. They believed in the social and political goals of the movement, but weren’t prepared to dig a trench on the front line to achieve them. For those who were ready to live in squats, fight policemen and radically alter their lives, music was important more for its message than its artistic qualities. Their spiritual (and perhaps literal) progeny reappeared in England in the late ’70s during the punk movement and again in the late ’80s with the New Age travellers and crusties.

Leading the radical faction was Mick Farren. Hoppy had dragged me to Shoreditch one snowy night in January to hear Mick’s group, the Social Deviants. I hadn’t much liked Hoppy’s description of them and when we entered the damp, chilly basement and got a glimpse of Mick’s gigantic white-boy Afro and his glum band-mates, I viewed the audition as even less promising, if that were possible. There is no twist in this tale; they were as bad as they looked. Mick’s singing was devoid of melody and his group could barely play their instruments. Hoppy conceded the point, but his unerring nose had spotted a willing and able trooper in Farren. I said the Deviants would play UFO over my dead body.

As predicted, Mick made himself indispensable. He saw that the girls handling UFO’s door money were in over their heads and took over the box office while fellow Deviants helped out as guards at the back door. Every week, he would ask me when they could have a booking. In unguarded moments he acknowledged that musically they were crap, but in his mind that detail was outweighed by their

commitment

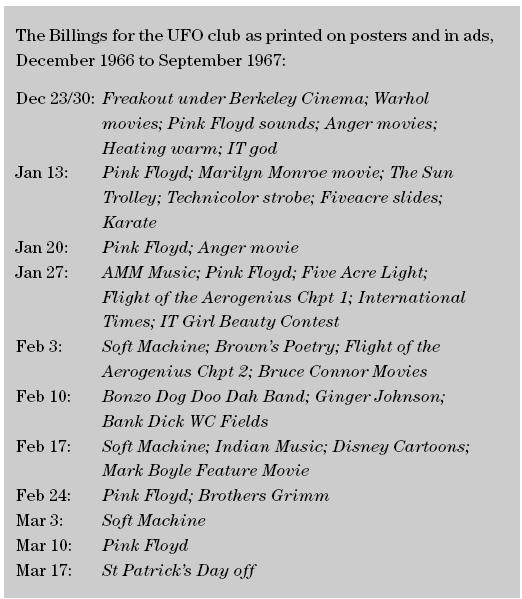

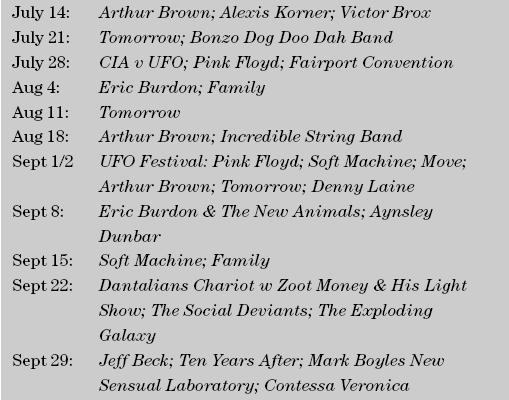

. I think he also imagined that once he strutted his tight jeans and mega-hair on the UFO stage, female adulation would be his. Despite my continued refusal to sully our stage with them, Mick and his boys became a key part of my support team. Eventually, after some sterling work coping with bigger and bigger crowds, I gave in. You can see them in the list of billings on 14 April 1967. At least I held out for three months.

Despite differing notions of what the revolution was about, an atmosphere of

agape

was pervasive in 1967: people were fundamentally quite nice to each other. Most hippies pitied, rather than hated, the ‘straights’. I suppose it helped that we were stoned much of the time. Another factor was Hoppy. Most movements are unified behind an inspiring leader at the outset and ours was no exception. It is difficult to over-emphasize the effect Hoppy had on the Underground community from the launch of the London Free School in October 1965 until his jailing in June 1967. At the LFS, then

IT

and UFO, his enthusiasm for music

and

revolution smoothed over most disagreements. He would propose an elegant compromise or point out the solution with such good-natured clarity that the corrected party never felt humiliated.

Gathered behind each of us were the massed ranks of our respective constituencies: his radicals who did so much of the hard work at both

IT

and UFO; my music fans ready for any new challenge to their eyes and ears. Hoppy and I saw this dichotomy as a source of strength rather than a problem and always had complete confidence in one another.

Tensions mounted as the regulars got crowded out of the increasingly popular club and Hoppy’s June trial date approached. Nothing so symbolized my apostasy in radical eyes as booking The Move. Ever since the club had become successful, I was determined to introduce our audience to my favourite

faux

psychedelics. When the staff heard about it, they were horrified. We were already swamped by ‘weekend hippies’ who were more likely to have downed a beer than a tab of Sandoz’s best before setting out. When the night arrived, the club was packed and the band played well enough, but the small stage inhibited them and perhaps the crowd did as well. It was a good, but not a great, night.

Hoppy’s role as Pied Piper of the Underground meant that policemen, journalists and outraged parents became aware of him. It has been suggested that the search warrant for his flat was triggered by a phone call from the worried and titled parent of a teenager who was dancing in the UFO lights, but it could have come from any one of a number of sources. We all assumed he would get off with a fine, but as the trial date approached the prosecution appeared to be playing for keeps. At a South London magistrates’ court in early June, we heard the eight-month sentence handed down. Everyone was devastated. Hoppy handed full control to me and I decided to try to make the club as commercially successful as I could. Half the profit would still go to Hoppy and he would need it when he came out.

THE SURGE IN ATTENDANCE and publicity UFO experienced during its first six months may have been in keeping with the

annus mirabilis

1967, but it was also part of a historic pattern. No matter how pure and impassioned the intention, the inevitable effect of most artistic or cultural revolutions is to feed the public’s appetite for titillation. London’s first commercial ‘hit’,

The Beggar’s Opera

(which ran almost continuously from 1721 to 1790), was based on the gallows confessions of highwaymen and cutpurses and the broadsheets that memorialized them. Clergy and Tory politicians were furious at its success; they felt it undermined all that was good and proper in English society. Which, of course, explains its popularity.

In the nineteenth century, the French refined the process by which the newly enlarged bourgeoisie avoided boring itself to death. Adventurous sons left the safety of the middle-class hearth, lived in sin with seamstresses in garrets, took to drugs or drink and espoused radical philosophies. They would then create a daring novel/ play/painting/poem/opera to provide vicarious thrills for those still working at their respectable jobs, earning enough as a result to reassume the trappings of bourgeois life in their old age. These rituals, speeded up and modernized (and extending now to daughters), can currently be followed in the popular press.

The twentieth century’s new twists to the old formulae involved drawing the audience farther into the subversive worlds celebrated by the artists. Few in the crowds attending

The Beggar’s Opera

dreamt of hanging out with thieves and murderers. Nineteenth-century audiences loved reading

Scènes de la Vie Bohème

and going to the opera, but would never trade their comfortable homes for garrets. And most wouldn’t tolerate their children getting up to any such behaviour.

White New Yorkers taking the A-train to Harlem in the ’20s to catch Duke Ellington at the Cotton Club demonstrated that audiences were becoming as interested in experiencing the dangerous ambience as they were in listening to the dangerous music or reading the dangerous book. When preachers fulminated against rock’n’roll for luring innocent white teenagers into sexually subversive black lifestyles or – heaven forfend! – dancing with black folk, they knew what they were talking about. Fifties teenagers were pushing the boat out that much farther than slumming jazz fans thirty years before.

What London witnessed in the spring of ’67 was more than an endorsement of a new musical style, it was a mass immersion in the sub-culture that gave rise to it. We saw them pour down the stairs week after week in search of a transcendent experience. Thanks to the chemistry in the back pockets of my security staff (freelance, of course, nothing to do with the club), they often found it. Drugs meant there was less of the toe-in-the-water tentativeness of the A-train passengers in 1928: at UFO, the grinning crocodile of psychedelics wrapped its lips around your ankle, dragged you in and licked you all over. Such experiences began to transform society, but not as we had hoped. By the summer, kaftans and beads were everywhere and UFO was swamped by tourists and weekend hippies. But were we anything more than the latest in a line of English style tribes, following Teddy boys, Rockers and Mods? We had aspired to greater things: to be as threatening to the good order of society as the authorities had feared.

The march to Fleet Street and Tomorrow’s dawn call to revolution ushered in July, but the month passed relatively calmly as our crowds continued to grow. When the

News of

the World

spiced the nation’s Sunday breakfast at the end of the month with shocking tales from the ‘Hippie Vice Den’, Mr Gannon got a call from a local policeman: if UFO opened that weekend, a warrant would be sought for a raid and his licence could be lost. Our Blarney Club days were over.

I persuaded Centre 42, playwright Arnold Wesker’s foundation for the encouragement of ‘workers’ theatre’, to rent us the Roundhouse, a magnificently decaying brick hulk at the edge of the railway yards in Camden Town. That Friday we handed out leaflets in front of the Blarney Club telling punters they could find UFO – starring the newly mind-blown Eric Burdon – a few stops away on the Northern Line. In some respects, the Roundhouse UFO was glorious. Its extraordinary space and huge stage were liberating after the cramped confines of the Blarney Club. I looked forward to a future of big crowds and soaring profits. One problem, however, was barely noticed that first night: after eleven, the local pubs filled the streets with their inebriated Irish and skinhead patrons. A few of our customers got hassled, but we thought little of it.

By the following week, word had spread. Skinheads hadn’t had too much contact with hippies up to then, but they could smell a natural enemy. The minute our audience arrived in the neighbourhood, they were under attack. Bells were snatched from around necks, handbags stolen, eyes blacked. A group of skins charged through a fire door and started hitting anyone they found, myself included. A few police came but they seemed to enjoy seeing the hippies getting a kicking.

Our door staff were useless against the thugs, so I turned to Michael X and his Black Nationalists to provide a security patrol. He showed up the following week with seven big, mean-looking guys in black turtlenecks, tight black trousers and shaved heads. I got to know a few of them later: an actor, a film director and a writer, and they could not have been gentler souls. But when they scowled and struck karate poses, the skinheads weren’t to know that, were they? Their services, however, didn’t come cheap.

Everywhere I turned, costs soared. The rent was far more than we had been paying Mr Gannon and I could no longer use the tiny capacity of my venue as an excuse for keeping musicians’ fees down. More lighting was needed and more staff. Commercial promoters, now regularly booking the Floyd, Soft Machine or Arthur Brown, had become competitors. The eager idealists who had worked long and hard began to fade away without Hoppy to inspire them. Week after week I paid out the door cash to musicians, staff and to cover expenses with little or nothing left for my rent or Hoppy’s nest egg. For the first time, UFO began to lose money.

There were some high points amid the gloom. The balcony platform that circled the Roundhouse halfway up the high brick walls inspired me to track down the company that had ‘flown’ Peter Pan during a recent production in the West End. Arthur Brown made his first Roundhouse entrance high over the audience, his head in the trademark halo of flame, with another novel device – a radio microphone – amplifying his vocal. For a moment, I thought the Roundhouse might be worth it after all.