Why Diets Fail (Because You're Addicted to Sugar) (26 page)

Read Why Diets Fail (Because You're Addicted to Sugar) Online

Authors: Nicole M. Avena

Cues can be visual, mental, auditory, or even olfactory (smelled). So, if you get the hankering for a can of soda while watching a movie, it may be the result of a cleverly placed product that is serving as a cue. If you get an urge to eat apple pie when you get to Grandma’s house, it may be your surroundings acting as a mental cue of the many pies that she has baked for you in the past. If you hear the music of the ice-cream truck coming down the road, you might suddenly be dying for a cone. If you are trying to cut down on sugar- and carbohydrate-rich foods, it’s important to recognize these powerful cues so that you can minimize the effect they may have on your food choices.

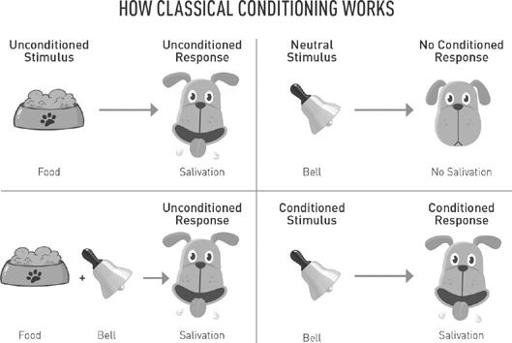

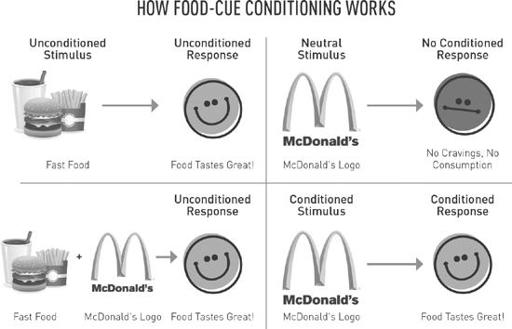

Let’s say you’re driving on the highway and see the logo of your favorite fast-food chain. You suddenly sense an urge to consume a certain food or drink from that place and decide to go there. This behavior is a typical example of classical conditioning. Classical conditioning is a learning technique first discovered by Ivan Pavlov, who is best known for his work conditioning dogs. Classical conditioning involves an unconditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, neutral stimulus, and conditioned response. An unconditioned stimulus triggers an unconditioned response naturally; it does not need to be learned. For instance, if you smell your favorite

food and then find yourself feeling hungry, the food’s flavor is serving as the unconditioned stimulus and your feeling of hunger is the unconditioned response. During classical conditioning, an unconditioned stimulus is associated with a neutral stimulus so that the neutral stimulus is able to elicit the unconditioned response, which is then called the conditioned response because it has been learned.

This is what happens when we see a food logo. We have become conditioned such that when we see the neutral stimulus of a logo (which is merely an image with which we associate meaning), we feel the urge to consume some food or drink. This is why when you see the McDonald’s arches, you can almost taste the french fries, and you may suddenly want to stop in and get some even if you aren’t hungry. This is also why McDonald’s has had the same basic logo since the company’s inception and has it advertised in as many places as it can: the arches are a cue that signals the availability of french fries. In fact, we are so programmed to want to obtain this

food reward that when we see the food cue, we anticipate the pleasure of eating. This anticipation helps to reinforce this association and behavior.

As a side note related to fast-food logos, there is evidence that children recognize these logos at a higher frequency than other food logos,

20

and scientists suggest that this increased recognition could lead children to influence their parents’ buying behaviors.

21

Numerous studies have also shown the effect that certain cues can have on our brains. Scientists have found that cues associated with drug use can elicit similar neurochemical responses as actual drug use. For instance, in rats, it has been shown that just being exposed to stimuli related to previous cocaine use can result in a release of dopamine in the brain,

22

and in humans, heightened neural activation in reward-related brain regions is seen in human drug addicts who are shown drug cues, like heroin paraphernalia.

23

Interestingly, studies reveal that people who are obese show stronger neural activation in response to food cues and seem to exert more effort to control their appetite when encountering these cues.

24

People who are overweight also tend to view pictures of food more readily than lean people, especially when they report having a food craving. Thus, when experiencing a food craving, an individual who is overweight may have a heightened awareness of the food cues around him. Being overweight has also been associated with greater snack food intake after viewing food cues than healthy-weight controls.

25

Cues do their job: they make us want to eat foods. And unfortunately, if you are overweight or obese, they may be even more effective.

So what can we do to control any programmed response we may have when we see, smell, hear, or are reminded of such food cues? The first and most important step is to recognize what these cues are doing. The second step is to recognize what

you

need, or do not need, to eat or drink in that moment. By being mindful of your own needs, instead of what corporations may try to encourage you to eat, you can make smart decisions regarding your diet despite exposure to food cues. Would you agree to buy something from a telemarketer who calls you persistently, even if you did not need the product they were selling? No. The same concept applies to food stimuli and rewards. With a telemarketer, you evaluate what you have and realize that you do not need what he is trying to sell you, despite his incessant attempts to convince you that you do, so you decline, hang up the phone, and move on with your day. Likewise, with food cues, you can move past them or change the channel and continue to stay on track with your long-term goals.

Have a Plan

As mentioned in Step 6, strategies that are recommended to help people successfully cope with cigarette cravings when trying to quit smoking may also be helpful when conquering an addiction to sugar, and especially when trying to avoid cravings for certain foods.

26

These include setting a time frame, such as fifteen minutes, when you first get a craving. Try to go for fifteen minutes without indulging the craving. At the fifteen-minute point, your craving may be less strong and easier to avoid, or you may have become engaged in or distracted by something else and forgotten about it altogether. If you experience a craving, it may be helpful again to list and reflect upon your long-term goals: why you are not indulging in these foods. Try to keep these long-term goals in mind when you find yourself craving an unhealthy food that will probably only satisfy you temporarily and, in the long run, may maintain a cycle of addiction.

When trying to conquer an addiction to sugar, cravings may threaten to hinder progress and long-term success. With a better understanding of what contributes to our cravings, however, we’re better prepared to handle them more effectively. This chapter has emphasized the importance of understanding why you crave certain foods versus others, when you tend to crave these foods, the influence of food cues in eliciting cravings, and the importance of variety when it comes to cravings. With this information and some of the suggestions included above, you should be better able to handle these cravings if they arise.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

• Are there any foods or drinks that you commonly crave?

• What is it about these foods or drinks that you find appealing or appetizing?

• Knowing this, what are some healthier foods or drinks that you may be able to use as substitutions? (You may want to use the

Sugar Equivalency Table

in the appendix as a guide.)

• Do you find that you tend to crave foods or drinks in certain circumstances (for example, when you are stressed, sad, or excited)? Aside from eating, how else might you respond to or cope with these situations or moods when they arise?

STEP 8

Avoiding a Relapse (and What to Do If One Occurs)

“

Always bear in mind that your own resolution to success is more important than any other one thing

.”

—

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

For some people, this might be the most important chapter in this book. Maybe you’ve been excited and committed to starting other diets before, but one poor food choice, one slipup that you regretted the minute you made it, left you feeling disappointed in yourself and discouraged about your ability to stick to a diet plan, and ultimately derailed you from continuing. This process of events—eating a certain food or more food than planned, which leads to negative thoughts and emotions (such as frustration, disappointment, and guilt), which leads to throwing in the towel—is

precisely what this chapter has been designed to help safeguard against.

First, let’s briefly describe how a

relapse

is defined. As mentioned in earlier chapters, sugars and other carbohydrate-rich foods are almost everywhere. In fact, they are even contained in many drinks and food items that people often consider healthy options (such as dried fruit, trail mixes, and protein or granola bars), so totally eliminating sugar from your diet would be nearly impossible. The goal of this plan is to eliminate the major sources of excess added sugars and other carbohydrates from your diet, such as sugary beverages and junk foods like candy bars and various desserts, as a way to reduce your overall sugar intake. So it isn’t as though if you consume some sugar you are relapsing or breaking the rules of this plan; consumption of a high amount of sugar, however, would constitute a regression, and if this continued over a longer period of time, this would constitute a relapse.

Before discussing what to do if a relapse occurs, it’s important to talk about some factors that can aid in preventing a relapse from occurring in the first place. The withdrawal symptoms and cravings discussed in Steps 6 and 7 represent possible risk factors for relapsing, but hopefully with the information covered in those chapters, you are better equipped to handle these challenges. Understanding the process and some of the symptoms associated with withdrawal can help you to identify and contextualize them as temporary indications that your body is adjusting to a new way of eating. Additionally, having an awareness of the types of foods you tend to crave, when you tend to crave them, and what function they serve for you can help you to develop alternative strategies that do not include giving in to food cravings. The concept of food cues has also been discussed in previous chapters, and it is important to be aware of these and to be confident about how you can handle them, as they

may also contribute to a relapse. In this chapter, several other factors that may be associated with relapse will be discussed.

Make Sure That You Are Thinking Straight