Why Growth Matters (24 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

Finally, it will be best to make the transfers unconditional except in the cases of elementary education and major illnesses. We lean in favor of vouchers for education and insurance for major illnesses. Given the limited administrative ability of the Indian government at all levels, adding conditions to the transfers will only result in corruption without delivering the desired outcome. The objective of influencing the consumption basket except in the case of elementary education and major illnesses should, instead, be pursued through alternative instruments. For example, nutrition improvement can be achieved through requiring fortification of key foods and informing the public on the necessity of nutritious foods and the dangers of alcohol, tobacco, and cigarette consumption. Education being a social goal, vouchers offer the best compromise between empowering the beneficiary and ensuring that the resources offered through education do get used for that purpose. It being relatively difficult to transfer the voucher or to sell in the open market, it is not likely to lead to large-scale corruption. Likewise, insurance is the most cost-effective instrument of assisting poor families in case of a major illness and is less likely to be abused.

Attacking Poverty by Guaranteeing Employment

T

he principal instrument of direct attack on poverty in India has been schemes providing employment to the poor in the rural areas. While the central and state governments have sponsored a variety of these schemes over the past decades, the central government-sponsored scheme launched under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) of 2005 eclipses them all in magnitude and scope.

1

Implemented over the entire country, this scheme is the principal vehicle for placing minimum purchasing power in the hands of rural households today. Therefore, we must examine the weaknesses in its design and functioning, and suggest reforms that would achieve the scheme's objective at lower cost and with greater effectiveness.

The NREGA has been implemented in three distinct phases. Under Phase I, which began February 2, 2006, it was implemented in the two hundred poorest districts nationwide. Under Phase II, an additional 130 districts were covered beginning April 1, 2007. The remaining 274 districts came under the scheme as part of Phase III, implemented with effect from April 1, 2008. Therefore, the scheme has been in operation over the entire country for four full financial years ending on March 31, 2012.

The broad contours of the NREGA are easily defined. The program guarantees one member of every rural household, whether poor or not, 100 days' worth of unskilled manual employment at a wage no less than

that specified by the central government. Originally specified at 60 rupees per day, the wage was revised to 100 rupees per day in January 2009. Beginning January 1, 2011, the wage has been linked to the consumer price index.

2

If an applicant is not provided employment within fifteen days of seeking it, the state is obliged to compensate him or her at a rate no less than one-fourth of the specified rate for the first thirty days and at no less than half of the wage rate for the rest of the period. The state is required to bear the burden of this compensation. At least one-third of the beneficiaries are required to be women who have registered and have requested work.

Labor hired as a part of the program is to be employed in public works and other activities specified in the legislation, such as water conservation and water harvesting; drought proofing, including forestation and tree planting; irrigation canals; land development; flood control; and rural connectivity. The cost of the material component of projects including skilled and semiskilled workers is capped at 40 percent of the total cost. The central government covers only 75 percent of the material cost, with the state having to fund the remaining 25 percent. The legislation makes very detailed provisions for creating the implementation machinery at the center, state, district, block, and village levels.

The closest parallel to the NREGA in developed countries is the massive employment program overseen by the Works Progress Administration (renamed Works Projects Administration or WPA in 1939) under President Franklin Roosevelt in the United States. The WPA employed millions of unskilled workers to carry out public works projects that included the construction of roads and public buildings. The scale of the program can be judged by the initial appropriation of the WPA at $4.9 billion in 1935, which amounted to a gigantic 6.7 percent of the GDP in that year.

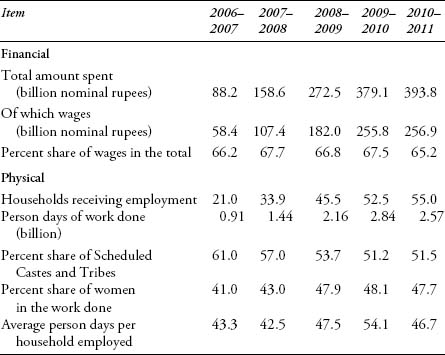

Table 14.1

reports the key achievements of the NREGA in terms of financial and physical indicators, as officially reported. Beginning with the total expenditure of 88.2 billion rupees ($1.9 billion) in 2006â2007, the program spent a total of 393.8 billion rupees ($8.6 billion) in 2010â2011. Of this, approximately two-thirds was spent on wages and the rest went to materials.

3

The number of households benefiting from the program rose from 21 million to 55 million over the same period. After the program peaked in 2009â2010, the total person days and person days per week declined slightly to 2.57 billion and 46.7 days, respectively, in 2010â2011. Clearly the average person days per household receiving employment under the program is well below the maximum one hundred days offered under the program.

Table 14.1. Key achievements of the NREGA as officially reported

Source: For years 2006â2007 and 2007â2008, see

www.nrega.net/csd/Forest/field-initiatives/Sustainable%20Developemnt.pdf

(accessed November 18, 2011) and for the last three years, see “DMU Report” at

http://nrega.nic.in/netnrega/home.aspx

(accessed November 18, 2011)

Going by just the wages paid, the NREGA program placed 4,671 rupees per household on average in 2010â2011 in the hands of the households covered by the program. But this average masks one key implication of

Table 14.1

: the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes benefited disproportionately from the program. According to the 2001 census, the Scheduled Castes and Tribes account for 24.4 percent of the

Indian population. But their share in the days worked in 2010â2011, shown in

Table 14.1

, was 51.5 percent. If we assume that the distribution of households by caste in the beneficiary population mirrors that in the general population, we would conclude that the Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) households received 2.2 times the average sum or approximately 10,275 rupees per household in 2010â2011. Of course, to the extent that the SC and ST households were represented more than proportionately among the beneficiary households, this figure would be lower. Whatever one assumes, the data do seem to point to a proportionately larger part of the benefit going to the SC and ST households that also happen to have a higher incidence of poverty.

Few critics would consider the scheme so counterproductive as to advocate its elimination even if no other antipoverty scheme replaced it. Indeed, most would agree that the NREGA has done more to transfer purchasing power to the poor than almost all existing redistribution programs, which include food, fertilizer, water, and electricity subsidies and even education and health expenditures. Even accepting that the NREGA is subject to significant leakages as the money flows from the center all the way down to the actual beneficiary, and that it has contributed to larger fiscal deficits and inflation and has adversely impacted economic activity by distorting the labor market, it is to be viewed positively vis-Ã -vis a situation without the NREGA insofar as it has placed a significant sum of money in the hands of poor households, at least going by the official statistics reported in

Table 14.1

.

But the picture looks much bleaker when we instead compare the situation with the NREGA to the one in which it is replaced by an

alternative

policy of making direct transfers to poor households. Advantages of such a transfer scheme over the NREGA are many, with almost no disadvantages.

First and foremost, transfers will virtually eliminate the leakages. The precise volume of leakages under the NREGA is not known but even the proponents of the scheme do not deny that they are significant. A study

by Sharma (2009), jointly sponsored by the National Council on Applied Economic Research and the Public-Interest Foundation, observed that leakages in Jharkhand, Orissa, and Uttar Pradesh went up to “one-third to half of the stipulated wages,” adding that since the leakages are disguised through the addition of fictitious names to the muster rolls, employment generation is also overstated. Sharma (2009) writes, “All three states have what is referred to as the PC or âpercentage' system in which bribes have to be paid according to fixed percentages to the whole hierarchy of staff up to the block level, and sometimes going higher” (p. 128, footnote 7). For Orissa, Sharma is able to provide more precise estimates. He notes, “The study estimates that only 58 percent of wages disbursed in sample works during the first two years of the program reached workers listed in the muster rolls, the proportion being only 26 percent in KBK [Kalahandi Balangir Koraput] region” (p. 129, footnote 8).

Cash transfers should substantially eliminate these leakages. Advances in technology now allow an official in New Delhi to deposit money into the bank account of the beneficiaries held in a distant village, using just a few keystrokes. The states of Rajasthan and Karnataka have recently experimented with cash transfers to widows and the elderly with strikingly positive results. Summarizing their study of these experiences, “Small But Effective: India's Targeted Unconditional Cash Transfers,” Dutta, Howes, and Murgai (2010) note:

India's approach to social security stresses the provision of subsidized food and public works. Targeted, unconditional cash transfers are little used, and have been hardly evaluated. An evaluation of cash transfers for the elderly and widows, based on the national household survey data and surveys on social pension utilization in two [states], Karnataka and Rajasthan, reveals that these social pension schemes work reasonably well. Levels of leakage are low, funds flow disproportionately to poorer rather than richer households, and there is strong evidence that the funds reach vulnerable individuals. A comparison with the public distribution system reveals that the main strength of the social pensions scheme is its relatively low level of leakage.

The authors are careful to note that the study is not decisive, since it relates to small-scale programs. Nevertheless, it greatly strengthens the case for giving cash transfers a further play rather than acquiescing to knee-jerk assertions by critics that they are not feasible or that they, too, will be subject to corruption equal to that in the existing schemes. The central government, which has repeatedly shied away from carrying out proper pilot projects, needs to evaluate the feasibility of the cash transfers on a larger scale.

Second, even assuming equal volume of leakages as under the NREGA, which is highly implausible, cash transfers will place a greater volume of purchasing power in the hands of the poor for other reasons. Thus, while NREGA gives the beneficiary a wage that is higher than what would prevail in the market absent this scheme, it takes away his or her labor in return. Under a cash transfer, the beneficiary will receive the equivalent amount of public money and will also get to keep his labor, for which he can earn additional wage in the market. Moreover, NREGA ends up spending 35 percent of the expenditures on materials. Under cash transfers, these funds will be available for distribution to the poor.

Furthermore, cash transfers will not suffer from an important regressive feature plaguing the NREGA. The NREGA provides that the labor of a worker can be used in the

provision of irrigation facility, horticulture plantation and land development facilities to land owned by households belonging to the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes or below poverty line families or to beneficiaries of land reforms or to the beneficiaries under the Indira Awas Yojana of the Government of India or that of the small farmers or marginal farmers as defined in the Agriculture Debt Waiver and Debt Relief Scheme, 2008.

4

Surely most workers offering their labor under the program are even poorer than some of the entities entitled to or benefiting from their free labor under this provision. In contrast, under a cash transfer, the workers retain the right to sell their labor at the market wage.

Then again, NREGA has also led to severe distortions in the labor market that cash transfers would avoid. Three such distortions are worth emphasizing. One, by diverting a fraction of the labor force from its productive private-sector deployment to public works projects, it has replaced genuine value added by projects likely to be of dubious value. Because NREGA funds can be accessed only for prespecified activities considered to serve public interest, local authorities have an incentive to come up with projects fitting this list even when the social return on them is low, possibly even minuscule. Normally it is the social return that drives the search for resources to finance a project. But NREGA reverses this process: the availability of the funds drives the search for projects.