Why Growth Matters (20 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

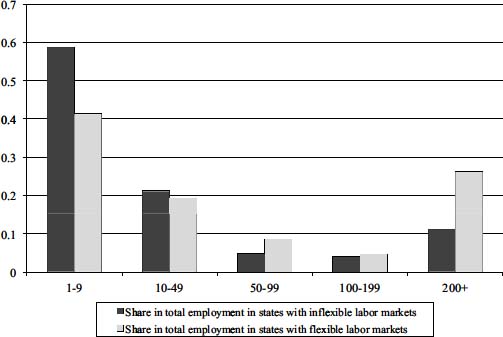

Figure 8.4. Firm-size distribution in labor-intensive manufacturing in states with flexible versus inflexible labor laws

Source: Hasan and Jandoc (2012)

To be sure that other factors are not behind the state-level differences, Hasan and Jandoc also compare states with good infrastructure to those without. But this comparison yields no real differences in the employment shares of large and small firms across states.

Almost all labor laws in India are more than four decades old, with the 1970 Contract Labor (Regulation and Abolition) Act being the last major labor legislation passed by an Indian parliament. At the time, these laws perhaps had some rationale in terms of redistribution in favor of the worker. Investment and import licensing gave guaranteed profits to the domestic firms that were lucky enough to get the licenses. Therefore, forcing them to share those profits with the workers through ultrahigh protection to the latter was defensible.

But with the investment and import licensing abolished and trade opened up, domestic firms are subject to intense competition. The same ultrahigh protection to workers in certain dimensions under these circumstances has only prevented the economy from specializing in the goods in which India enjoys comparative advantage. If India is to move its economy toward specialization in labor-intensive products, which is essential to creating far more formal-sector jobs, and therefore for making growth more inclusive, reform of the labor laws is urgent.

Ideally, India needs to reform the labor laws wholesale. But labor legislation is among the toughest to manage politically. So reform may well have to focus first on the most damaging laws on the books. The law in the most urgent need of reform is the 1947 Industrial Disputes Act. This legislation is stacked too heavily against the employers to leave sufficient incentive for a massive expansion of employment-intensive sectors. With the wages in China reaching levels at which it is likely to be forced out of these sectors, India is well positioned to become the world's manufacturing hub. But if the costs of employment remain as they are, that opportunity is likely to be seized by a large number of smaller countries, such as Vietnam and Bangladesh. These countries allow firms to hire and fire workers under reasonable conditions and maintain a balance between the rights of both workers and employers. As a result, large firms in sectors such as apparel can be found aplenty in both countries and both have also seen significantly faster growth of the sector and done extremely well on the export front.

Several changes in the IDA would be enormously helpful. First, the definition of retrenchment for purposes of industrial disputes (in firms of all sizes) needs to be tightened. The IDA defines retrenchment as “the termination by the employer of the service of a workman for any reason whatsoever” other than a punishment inflicted by way of disciplinary action; voluntary retirement; retirement upon reaching the age stipulated in the contract; and termination due to nonrenewal of a contract after it expires or failure of the worker to meet conditions stipulated in the contract. Under this definition, even a discharge of employees due to declining sales or unanticipated change in technology would be interpreted as retrenchment. Debroy (2001) laments that under this definition, Indian courts have even gone on to interpret as retrenchment the discharge of an employee on probation and nonconfirmation of an employee failing a test required for confirmation. The provision has naturally resulted in the multiplication of industrial disputes as well as a disincentive to hire workers. A tighter definition of retrenchment for purposes of industrial disputes would clearly bring down the number of such disputes and encourage more hiring of workers.

16

Second, the IDA allows every single industrial dispute to go to the labor courts and tribunals. This practice should be replaced by one under which an independent authority is empowered to deliver a time-bound and final verdict in a designated class of cases. At least in cases in which the basis of retrenchment is not in dispute (for example, in the Nakate case), the independent authority can be authorized to give a final verdict within the rules under which retrenchment is permitted.

Third, Section 9A of the IDA, which imposes a heavy burden on an employer wishing to reassign a worker to an alternative task, needs to be replaced by one that gives the employer greater flexibility. Minimally, the employer should be permitted to reassign the worker to a set of prespecified tasks on short notice and without challenge. For example, if a change in technology renders the task of an existing employee redundant, the employer should have a clear right to assign him or her to an alternative task for which he or she is qualified. More broadly, the employer should have the right to reassign workers within a broad set of prespecified tasks.

Fourth, while the IDA prohibits strikes by public utility services without notice, no such restrictions apply to strikes in other industrial establishments except during conciliation or arbitration proceedings. Nor does the law require a secret ballot by trade union members to call a strike. This state of affairs encourages wildcat strikes that can be very harmful to the health of the establishment. Change in the IDA in this regard is necessary.

Fifth, Chapter VB of the 1947 IDA, which makes it nearly impossible to lay off workers in a factory with one hundred or more workers under any circumstances, needs to be repealed. Interestingly, this chapter was added only in 1976; the IDA had existed for twenty-nine years without it, and India needs to return to the pre-1976 IDA. With careful steering, this may be politically doable. For example, the government could begin the process by changing the law for a handful of labor-intensive sectors in which there are only a few large firms in the first place. For instance, if the apparel distributions shown in

Figures 8.2

and

8.3

are still valid, repeal of chapter V-B in this sector will impact only a small number of employees who could be exempted. If even this is politically difficult, the initial change could be started with exemption for apparel factories with one hundred to five hundred workers, which account for a tiny proportion of the employment in the sector, making it even easier to exempt the existing employees.

Among other labor laws, the 1948 Factories Act should be revisited to see if it contains provisions that are too onerous for firms with ten or even twenty workers. Our own reading of the act is that small firms are unlikely to have the staff and expertise to understand and ensure fulfillment of the myriad regulations in the act. If this reading is correct, there is a need for an alternative set of fewer and more manageable regulations applicable to firms that employ fewer than fifty workers. Successful large firms often emerge from smaller firms and a case is to be made for giving greater leeway to the latter.

The 1926 Trade Unions Act also needs to be modified. It has led to a proliferation of trade unions in larger firms. Originally this law allowed any seven workers to form a trade union. A 2001 amendment introduced the qualification that those forming the trade unions should minimally

include 10 percent of the workforce or one hundred workers. But even this amendment leaves room for a large number of trade unions in larger firms. As a result, we find that the Neyveli Lignite Corporation Limited has as many as fifty trade unions and associations.

17

This organizational feature makes the collective-bargaining process highly problematic since an agreement reached with one union does not automatically apply to another. There needs to be further reform of the act that would limit the number of trade unions to a manageable level.

Is there any way to provide minimal social protections to the myriad workers in the informal sector, often consisting of establishments of fewer than ten workers? Such protection seems impractical in view of their extremely large number. In our view, the solution must be indirect and lies in the labor-market reforms we have proposed, which should accelerate the growth in formal-sector employment, skill creation that will make workers employable in better-paid jobs, and strengthening the Track II redistributive programs (discussed in depth in

Part III

of this book) that enhanced growth from Track I reforms make possible through increased revenues.

Land Acquisition

L

ike labor, land represents yet another factor that has remained largely untouched by the post-1991 reforms. The antiquated and dysfunctional state of regulations concerning land acquisition creates serious economic inefficiencies.

The 1894 Land Acquisition Act, which lays out key regulations, is more than a century old. Though the act has been amended several times, with the last major amendment in 1984, its basic provisions remain intact and the process of land acquisition continues to be archaic.

At least two issues need to be addressed in the matter of land acquisition. First, if land is to be acquired from a private party, the government must define the “social purpose” for which it can be so acquired. Second, the price at which the owner is to be compensated must be calculated.

The definition of “social purpose” to acquire land is not an exclusively economic issue. In the United States, the Supreme Court recently allowed “taking” private property for social purpose to include building a mall on the grounds that, without the mall, the town would not be able to raise enough revenue to survive. The judgment had the support of liberal (i.e., progressive) judges, such as Justice Stephen Breyer. Yet, there was a hue and cry in several states, and legislation was advanced to overturn the judgment.

Ultimately the decision on what is legitimate social purpose for acquiring land has to be democratically determined. The Indian experience has been disruptive because the government has acquired privately

owned land at below-market prices and handed it over to industrialists in Special Economic Zones and for housing projects by private builders and large-scale industrial projects by private businesses. Violence erupted in the case of the Tata Nano project in Singur in West Bengal, which eventually had to be moved to Gujarat, and in the case of the Orissa Steel project proposed by the Korean firm POSCO.

The original intention behind compulsory land acquisition was to prevent a few holdouts from delaying a “socially necessary” project, such as the building of a highway or a railroad. No such acquisition was to be undertaken on a massive scale at less than market-value prices, which amounts to a levy on the private owners whose land was being acquired. This original purpose needs to be restored. Any significant acquisition of land cannot be at less than market prices, especially since this also amounts to a regressive tax whose proceeds typically are shared between the government and the beneficiaries who usually are substantial private parties.

Instead, the current legislation enables a rip-off of private landowners by unscrupulous state governments and large industrialists who offer to bring their projects to these states. For example, as Panagariya (2008b) has recounted, the conflict in Singur, West Bengal, surrounding the Nano car project of Tata Motors had its origins in a secret tripartite agreement in March 2007 between the latter on the one hand and the West Bengal government and West Bengal Industrial Development Corporation on the other. While floating its plans for this small-car project, Tata Motors had pitted the states of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and West Bengal against one another in a bidding war. In the end, West Bengal won by promising the company prime land at a throwaway price in Singur, a town just thirty miles northwest of Calcutta, and substantial other subsidies at the cost of the general taxpayer.

The corporation did not finance the extraordinarily cheap land with a subsidy. Instead it forcibly acquired the land for a pittance in the most opaque manner, asking farmers to transfer their land even before it told them the price! The mobilization of farmers by the opposition politician Mamata Banerjee against the heavy-handed tactics of the government

and the meager compensation it offered for the land eventually forced Tata Motors out of Singur.

1

Therefore, there is much to be said for leaving the purchase of land to be undertaken at market prices. Is there still a rationale, which underlies the origin of the forced acquisition legislation, for the government to intervene because some private owners might hold out to extract exorbitant prices? The representatives of business interests as well as landowners have argued that the government must remain involved to resolve this problem. But to our knowledge, this is an infrequent, even rare possibility in practice. In states such as Gujarat, Punjab, and Karnataka, land acquisition for numerous projects has been accomplished smoothly through direct negotiation between private parties. With land costs being a tiny proportion of the total costs, industrialists have been in a good position to make the deal attractive to the sellers.

2