Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (16 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

I took a few other seminars from Jack and since this was before I was a "skeptic," I can honestly say I tried to experience what others seemed to— but it always eluded me. In retrospect, I think what was going on had to do with the fact that some people are fantasy-prone, others are open to suggestion and group influence, while still others are good at letting their minds slip into altered states of consciousness. Since I think near-death experiences are a type of altered state of consciousness, let us examine this concept next.

What Is an Altered State of Consciousness?

Most skeptics would agree with me that mystical and spiritual experiences are nothing more than the product of fantasy and suggestion, but many would question my third explanation of altered states of consciousness. James Randi and I have discussed this subject at length. He, along with other skeptics like psychologist Robert Baker (1990, 1996), believes that there is no such thing as an altered state of consciousness because there is nothing you can do in a so-called altered state that you cannot do in an unaltered state (i.e., normal, awake, and conscious). Hypnosis, for example, is often considered a type of altered state, yet hypnotist "The Amazing" Kreskin offers to pay $100,000 to anyone who can get someone to do something under hypnosis that they could not do in an ordinary wakeful state. Baker, Kreskin, Randi, and others think that hypnosis is nothing more than fantasy role-playing. I disagree.

The expression

altered states of consciousness

was coined by parapsychologist Charles Tart in 1969, but mainstream psychologists have been aware for some time of the fact that the mind is more than just conscious awareness. Psychologist Kenneth Bowers argues that experiments prove that "there is something far more pervasive and subtle to hypnotic behavior than voluntary and purposeful compliance with the perceived demands of the situation" and that "the 'faking hypothesis' is an entirely inadequate interpretation of hypnosis" (1976, p. 20). Stanford experimental psychologist Ernest Hilgard discovered through hypnosis a "hidden observer" in the mind aware of what is going on but not on a conscious level, and that there exists a "multiplicity of functional systems that are hierarchically organized but can become dissociated from one another" (1977, p. 17). Hilgard typically instructed his subjects as follows:

When I place my hand on your shoulder (after you are hypnotized) I shall be able to talk to a hidden part of you that knows things are going on in your body, things that are unknown to the part of you to which I am now talking. The part to which I am now talking will not know what you are telling me or even that you are talking... . You will remember that there is a part of you that knows many things that are going on that may be hidden from either your normal consciousness or the hypnotized part of you. (Knox, Morgan, and Hilgard 1974, p. 842)

This dissociation of the hidden observer is a type of altered state.

What exactly do we mean by an altered state or, for that matter, an unaltered state? Here it might be useful to distinguish between

quantitative

differences—those of degree—and

qualitative

differences—those of kind. A pile of six apples and a pile of five apples are quantitatively different. A pile of six apples and a pile of six oranges are qualitatively different. Most differences between states of consciousness are quantitative, not qualitative. In other words, in both states a thing exists, just in different amounts. For example, when sleeping, we think, since we dream; we form memories, since we can remember our dreams; and we are sensitive to our environment, though considerably less so. Some people walk and talk in their sleep, and we can control sleep, planning to get up at a certain time and doing so fairly reliably. In other words, while asleep we just do less of what we do while awake.

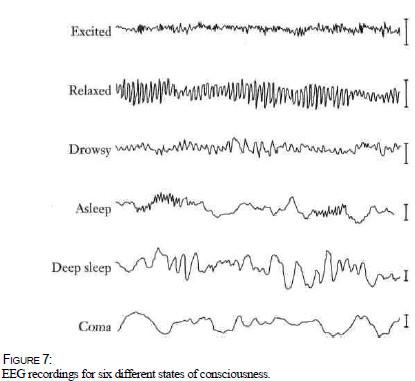

Still, sleep is a good example because it is so different that we do not normally mistake it for a waking state. The quantitative difference is so great as to be qualitatively different and thus count as an altered state. Though the EEG readings in figure 7 are only quantitatively different, they are so much so that the states they represent may be considered as different in kind. If a coma is not an altered state, I do not know what is. And it cannot be duplicated in a conscious state.

Consciousness has two characteristics: " 1.

Monitoring

ourselves and our environment so that perceptions, memories, and thoughts are accurately represented in awareness; 2.

Controlling

ourselves and our environment so that we are able to initiate and terminate behavioral and cognitive activities" (Kihlstrom 1987, p. 1445). Thus, an altered state of consciousness would have to interfere with our accurate monitoring of percepts, memories, and thoughts, as well as disrupt control of our behavior and cognition within the environment.

An altered state of consciousness exists when there is significant interference with our monitoring and control of our environment.

By significant, I mean a dramatic departure from "normal" functioning. Both sleep and hypnosis do this, as do hallucinations, near-death experiences, out-of-body experiences, and other altered states.

Psychologist Barry Beyerstein makes a similar argument in defining altered states of consciousness as the modification of specific neural systems "by disease, repetitive stimulation, mental manipulations, or chemical ingestion" such that "our perception of ourselves and the world can be profoundly altered" (1996, p. 15). Psychologist Andrew Neher (1990) calls them "transcendent states," which he defines as sudden and unexpected alterations of consciousness intense enough to be overwhelming to the person experiencing them. The key here is the

intensity

of the experience and the

profundity

of the alteration of consciousness. Do we do anything in an altered state that we cannot do in an unaltered state of consciousness?

Yes. For example, dreams are significantly different from waking thoughts and daydreams. The fact that we normally never confuse the two is an indication of their qualitative difference. Further, hallucinations are not normally experienced in a stable, awake state unless there is some intervening variable, such as extreme stress, drugs, or sleep deprivation. Near-death experiences and out-of-body experiences are so unusual that they often stand out as life-changing events.

No. The differences are only quantitative. But even here, it could be argued that the differences are so great as to constitute a qualitative difference. You can show me that the EEGs recorded when I am normally conscious and when I am hallucinating severely are only quantitatively different, but I have no trouble experiencing and recognizing their dramatic difference. Consider the near-death experience.

The Near-Death Experience

One of the driving forces behind religions, mysticism, spiritualism, the New Age movement, and belief in ESP and psychic powers is the desire to transcend the material world, to step beyond the here-and-now and pass through the invisible into another world beyond the senses. But where is this other world and how do we get there? What is the appeal of some place we know absolutely nothing about? Is death merely a transition to this other side?

Believers claim that we do know something about the other side through a phenomenon called the

perithanatic

or

near-death experience (NDE).

The NDE, like its related partner the

out-of-body experience (OBE),

is one of the most compelling phenomena in psychology. Apparently, upon a close encounter with death, some individuals' experiences are so similar as to lead many to believe that there is an afterlife or that death is a pleasant experience or both. The phenomenon was popularized in 1975 substantiated by corroborative evidence from others. For example, cardiologist E Schoonmaker (1979) reported that 50 percent of the more than two thousand patients he treated over an eighteen-year period had NDEs. A 1982 Gallup poll found that one out of twenty Americans had been through an NDE (Gallup 1982, p. 198). And Dean Sheils (1978) has studied the cross-cultural nature of the phenomenon.

When NDEs first came into prominence, they were perceived as isolated, unusual events and were dismissed by scientists and medical doctors as either exaggerations or flights of fantasy by highly stressed but very creative minds. In the 1980s, however, NDEs gained credibility through the work of Elisabeth Kiibler-Ross, a medical doctor who publicized this now-classic example:

Mrs. Schwartz came into the hospital and told us how she had had a near-death experience. She was a housewife from Indiana, a very simple and unsophisticated woman. She had advanced cancer, had hemorrhaged and was put into a private hospital, very close to death. The doctors attempted for 45 minutes to revive her, after which she had no vital signs and was declared dead. She told me later that while they were working on her, she had an experience of simply floating out of her physical body and hovering a few feet above the bed, watching the resuscitation team work very frantically. She described to me the designs of the doctors' ties, she repeated a joke one of the young doctors told, she remembered absolutely everything. And all she wanted to tell them was relax, take it easy, it is all right, don't struggle so hard. The more she tried to tell them, the more frantically they worked to revive her. Then, in her own language, she "gave up" on them and lost consciousness. After they declared her dead, she made a comeback and lived for another year and a half. (1981, p. 86)

This is a typical NDE, characterized by one of the three most commonly reported elements: (1) a floating OBE in which you look down and see your body; (2) passing through a tunnel or spiral chamber toward a bright light that represents transcendence to "the other side"; (3) emerging on the other side and seeing loved ones who have already passed away or a Godlike figure. It seems obvious that these are hallucinatory wishful-thinking experiences, yet Kiibler-Ross has gone out of her way to verify the stories. "We've had people who were in severe auto accidents, had no vital signs and told us how many blow torches were used to extricate them from the wreck" (1981, p. 86). Even more bizarre are stories of an imperfect or diseased body becoming whole again during an NDE. "Quadriplegics are no longer paralyzed, multiple-sclerosis patients who have been in wheelchairs for years say that when they were out of their bodies, they were able to sing and dance."

Memories from a previously whole body? Of course. A close friend of mine who became a paraplegic after an automobile accident often dreamed of being whole. It was not at all unusual for her to wake in the morning and fully expect to hop out of bed. But Kiibler-Ross does not buy the prosaic explanation: "You take totally blind people who don't even have light perception, don't even see shades of gray. If they have a near-death experience, they can report exactly what the scene looked like at the accident or hospital room. They have described to me incredibly minute details. How do you explain that?" (1981, p. 90). Simple. Memories of verbal descriptions given by others during the NDE are converted into visual images of the scene and then rendered back into words. Further, quite frequently patients in trauma or surgery are not totally unconscious or under the anesthesia and are aware of what is happening around them. If the patient is in a teaching hospital, the attending physician or chief resident who performs the surgery would be describing the procedure for the other residents, thus enabling the NDE subject to give an accurate description of events.

Something is happening in the NDE that cries out for explanation, but what? Physician Michael Sabom, in his 1982

Recollections of Death,

drew on the results of his correlational study of a large number of people who had had NDEs, noting age, sex, occupation, education, and religious affiliation, along with prior knowledge of NDEs, possible expectations as a result of religious or prior medical knowledge, the type of crisis (accident, arrest), location of crisis, method of resuscitation, estimated time of unconsciousness, description of the experience, and so on. Sabom followed these subjects for years, re-interviewing them as well as members of their families to see whether they altered their stories or found some other explanation for the experience. Even after years, every subject felt just as strongly about his or her experience and was convinced that the episode did occur. Almost all stated that the experience had a definite impact on their outlook on life and perception of death. They were no longer "afraid" of dying nor did they "mourn" the death of loved ones, as they were convinced that death is a pleasant experience. Each felt that he or she had been given a second chance and, although not every subject became "religious," they all felt a need to "do something with their lives."

Although Sabom notes that nonbelievers and believers had similar experiences, he fails to mention that we have all been exposed to the Judeo-Christian worldview. Whether or not we consciously believe, we have all heard similar ideas about God and the afterlife, heaven and hell. Sabom also does not point out that people of different religions see different religious figures during NDEs, an indication that the phenomenon occurs within the mind, not without.