Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (17 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

What naturalistic explanations can be offered for NDEs? An early, speculative theory came from psychologist Stanislav Grof (1976; Grof and Halifax 1977), who argued that every human being has already experienced the characteristics of the NDE—the sensation of floating, the passage down a tunnel, the emergence into a bright light—birth. Perhaps the memory of such a traumatic event is permanently imprinted in our minds, to be triggered later by an equally traumatic event—death. Is it possible that recollection of perinatal memories accounts for what is experienced during an NDE? Not likely. There is no evidence for infantile memories of any kind. Furthermore, the birth canal does not look like a tunnel and besides the infant's head is normally down and its eyes are closed. And why do people who are born by cesarean section have NDEs? (Not to mention that Grof and his subjects were experimenting with LSD—not the most reliable method for retrieving memories, since it creates its own illusions.)

A more likely explanation looks to biochemical and neurophysiological causes. We know, for example, that the hallucination of flying is triggered by atropine and other belladonna alkaloids, some of which are found in mandrake and jimsonweed and were used by European witches and American Indian shamans. OBEs are easily induced by dissociative anesthetics such as the ketamines. DMT (dimethyltryptamine) causes the perception that the world is enlarging or shrinking. MDA (methylene-dioxyamphetamine) stimulates the feeling of age regression so that things we have long forgotten are brought back into memory. And, of course, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) triggers visual and auditory hallucinations and creates a feeling of oneness with the cosmos, among other effects (see Goodman and Gilman 1970; Grinspoon and Bakalar 1979; Ray 1972; Sagan 1979; Siegel 1977). The fact that there are receptor sites in the brain for such artificially processed chemicals means that there are naturally produced chemicals in the brain that, under certain conditions (the stress of trauma or an accident, for example), can induce any or all of the experiences typically associated with an NDE. Perhaps NDEs and OBEs are nothing more than wild "trips" induced by the extreme trauma of almost dying. Aldous Huxley's

Doors of Perception

(whence the rock group The Doors got its name) has a fascinating description, made by the author while under the influence of mescaline, of a flower in a vase. Huxley describes "seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation—the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence" (1954, p. 17).

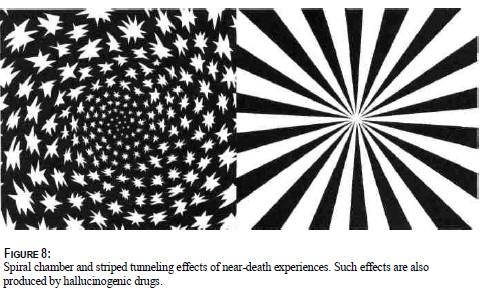

Psychologist Susan Blackmore (1991, 1993, 1996) has taken the hallucination hypothesis one step further by demonstrating why different people would experience similar effects, such as the tunnel. The visual cortex on the back of the brain is where information from the retina is processed. Hallucinogenic drugs and lack of oxygen to the brain (such as sometimes occurs near death) can interfere with the normal rate of firing by nerve cells in this area. When this occurs "stripes" of neuronal activity move across the visual cortex, which is interpreted by the brain as concentric rings or spirals. These spirals may be "seen" as a tunnel. Similarly, the OBE is a confusion between reality and fantasy, as dreams can be upon first awakening. The brain tries to reconstruct events and in the process visualizes them from above—a normal process we all do when "decenter-ing" ourselves (when you picture yourself sitting on the beach or climbing a mountain, it is usually from above, looking down). Under the influence of hallucinogenic drugs, subjects saw images like those in figure 8; such images produce the tunneling effect of the NDE.

Finally, the "otherworldliness" of the NDE is produced by the dominance of the fantasy of imagining the other side, visualizing our loved ones who died before, seeing our personal God, and so on. But what happens to those who do not come back from an NDE? Blackmore gives this reconstruction of death: "Lack of oxygen first produces increased activity through disinhibition, but eventually it all stops. Since it is this activity that produces the mental models that give rise to consciousness, then all this will cease. There will be no more experience, no more self, and so that... is the end" (1991, p. 44). Cerebral anoxia (lack of oxygen), hypoxia (insufficient oxygen), or hypercardia (too much carbon dioxide) have all been proposed as triggers of NDEs (Saavedra-Aguilar and Gomez-Jeria 1989), but Blackmore points out that people with none of these conditions have had NDEs. She admits, "It is far from clear, as yet, how they are best to be explained. No amount of evidence is likely to settle, for good, the argument between the 'afterlife' and 'dying brain' hypotheses" (1996, p. 440). NDEs remain one of the great unsolved mysteries of psychology, leaving us once again with a Humean question: Which is more likely, that an NDE is an as-yet-to-be explained phenomenon of the brain or that it is evidence of what we have always wanted to be true—immortality?

The Quest for Immortality

Death, or at least the end of life, appears to be the outer limit of our consciousness and the frontier of the possible. Death is the ultimate altered state. Is it the end, or merely the end of the beginning? Job asked the same question: "If a man die, shall he live again?" Obviously no one knows for sure, but plenty of folks think they do know, and many of them are not shy about trying to convince the rest of us that their particular answer is the correct one. This question is one of the reasons that there are literally thousands of organized religions in the world, each claiming exclusive knowledge about what follows death. As humanist scholar Robert Ingersoll (1879) noted, "The only evidence, so far as I know, about another life is, first, that we have no evidence; and secondly, that we are rather sorry that we have not, and wish we had." Without some belief structure, however, many people find this world meaningless and without comfort. The philosopher George Berkeley (1713) penned this example of such sentiments: "I can easily overlook any present momentary sorrow when I reflect that it is in my power to be happy a thousand years hence. If it were not for this thought I had rather be an oyster than a man."

In one of Woody Allen's movies, his physician gives him one month to live. "Oh, no," he moans, "I only have thirty days to live?" "No," the doctor responds, "twenty-eight; this is February." Are we this bad? Sometimes. It might be splendid if we were all to adopt Socrates' reflectiveness just before his state-mandated suicide: "To fear death, gentlemen, is nothing other than to think oneself wise when one is not; for it is to think one knows what one does not know. No man knows whether death may not even turn out to be the greatest of blessings for a human being; and yet people fear it as if they knew for certain that it is the greatest of evils" (Plato 1952, p. 211). But most people feel more like Berkeley and his oyster, and thus, as Ingersoll

was fond of pointing out, we have religion. But the quest for immortality is not restricted to the religious. Wouldn't we all like to live on in some capacity? We can, indirectly, and, if science can accomplish what some hope it will, perhaps even in reality.

Science and Immortality

Because purely religious theories of immortality—based on faith, not reason—are not testable, I will not discuss them here. Frank Tipler's

Physics of Immortality

is the subject of chapter 16 of this book, as Tipler's work requires extensive analysis. Suffice it to say that by "immortality" most people do not mean merely living on through one's legacy, whatever it may be. As Woody Allen said, "I don't want to gain immortality through my work; I want to gain immortality through not dying." Most people would not be content with the argument that parents are immortal in the sense that a significant part of their genetic make-up lives on in the genes of their offspring. From an evolutionary viewpoint, 50 percent of a person's genes live on in their offspring, 25 percent in their grandchildren, 12.5 percent in each great grandchild, and so on. What most of us think of as "real" immortality is living forever, or at least considerably longer than the norm. The rub is that it seems certain that the process of aging and death is a normal, genetically programmed part of the sequence of life. In evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins's (1976) scenario, once we've passed reproductive age (or at least the period of intense and regular participation in sexual activity), then the genes have no more use for the body. Aging and death may be the species' way of eliminating those who are no longer genetically useful but are still competing for limited resources with those whose job it now is to pass along the genes.

To extend life significantly, we must understand the causes of death. Basically there are three: trauma, such as accidents; disease, such as cancer and arteriosclerosis; and entropy, or senescence (aging), which is a naturally occurring, progressive deterioration of various biochemical and cellular functions that begins early in adult life and ultimately results in an increased likelihood of dying from trauma or disease.

How long can we live? The

maximum life potential

is the age at death of the longest-lived member of the species. For humans, the record for the oldest documented age ever achieved is 120 years. It is held by Shigechiyo Izumi, a Japanese stevedore. There are many undocumented claims of people living beyond 150 years and even up to 200 years; these frequently involve such cultural oddities as adding the ages of father and son together. Data on documented centenarians (people who live to be 100 years old) reveal that only one person will live to be 115 years old for every 2,100 million (2.1 billion) people. Today's world population of slightly over five billion is likely to produce only two or three individuals who will reach 115 years old.

Life span

is the age at which the average individual would die if there were no premature deaths from accidents or disease. This age is approximately 85 to 95 years and has not changed for centuries, and probably millennia. Life span, like maximum life potential, is probably a fixed biological constant for each species.

Life expectancy

is the age at which the average individual would die when accidents and disease have been taken into consideration. In 1987, life expectancy for women in the West was 78.8 years and for men 71.8 years, for an overall expectancy of 75.3 years. Worldwide, in 1995 life expectancy was estimated at 62 years. The numbers are continually on the rise. In the United States, life expectancy was 47 years in 1900. By 1950 the figure had climbed to 68. In Japan, the life expectancy for girls born in 1984 is 80.18 years, making it the first country to pass the 80 mark. It is unlikely, however, that life expectancy will ever go higher than the life span of 85 to 95.

Though aging and death do appear to be certain, attempts to extend the biological functions of humans for as long as possible are slowly moving away from the lunatic fringe into the arena of legitimate science. Organ replacements, improved surgical techniques, immunizations against most major diseases, advanced nutritional knowledge, and the awareness of the salubrious effects of exercise have all contributed to the rapid rise in life expectancy.

Another futuristic possibility is

cloning,

the exact duplication of an organism from a body cell (which is diploid, or has a full set of genes, as opposed to a sex cell, which is haploid, or has only a half set of genes). Cloning lower organisms has been accomplished but the barriers to cloning humans are both scientific and ethical. If these barriers go down, cloning may play a significant role in life extension. One of the major problems with organ transplantation is the rejection of foreign tissue. This issue would not exist with duplicate organs from a clone—just raise your clone in a sterile environment to keep the organs healthy, and then replace your own aging parts with the clone's younger, healthier organs.

The ethical questions associated with this scenario are challenging, to say the least. Is the clone human? Does the clone have rights? Should there be a union for clones? (How about a new ACLU, the American Clone Liberties Union?) Is the clone a separate and independent individual? If no, then what about your individuality, since there is one of you living in two bodies? If yes, then are there two of "you"? For that matter, if you replace so many organs that all your original organs are gone, are you still "you"? If you believe in the Judeo-Christian form of immortality and you clone yourself, is there one soul or two?

Finally, there is the fascinating field of

cryonic suspension,

or what Alan Harrington calls the "freeze-wait-reanimate" process. The principles of the procedure are relatively simple, the application is not. When the heart stops and death is officially pronounced, all the blood is removed and replaced with a fluid that preserves the organs and tissues while they are in a frozen state. Then, no matter what kills us—accident or disease—sooner or later the technologies of the future should be equal to the task of reviving and curing us.

Cryonics is still so new and experimental that the ethical questions have yet to come to public attention. For now, cryonic suspension is considered by the government as a form of burial, and individuals are frozen after they are declared legally dead by natural means, never by choice. If cryonicists could succeed in reviving someone, the distinction between the living and the dead would blur. Life and death would become a continuum instead of the discrete states they have always been. Certainly, definitions of death would have to be rewritten. And what about the problem of the soul? If there is such a thing, where does it go while the body is in cryonic suspension? If an individual chooses to be put into cryonic suspension before he is actually dead, then is the technician committing murder? Would it be murder only if the reanimation procedure failed to revive this suspended individual?