Why We Love Serial Killers (13 page)

Read Why We Love Serial Killers Online

Authors: Scott Bonn

Psychopathic serial killers do not value human life and they are insensitive and brutal while interacting with their victims. This is particularly evident in sexually motivated serial killers who stalk, assault, and kill their victims without any sign of remorse. Some derive great pleasure from spending time with and torturing their victims for lengthy periods before killing them. Such behavior extends and heightens the excitement and gratification for a psychopathic serial killer. Dennis Rader (BTK) is a classic example of a psychopathic power/control serial killer who did this. In truly psychopathic fashion, Rader has compared himself to a venomous snake or scorpion. He rationalizes his killings as the rational acts of a natural born predator. Rader has said that his control over the life and death of his victims made him God.

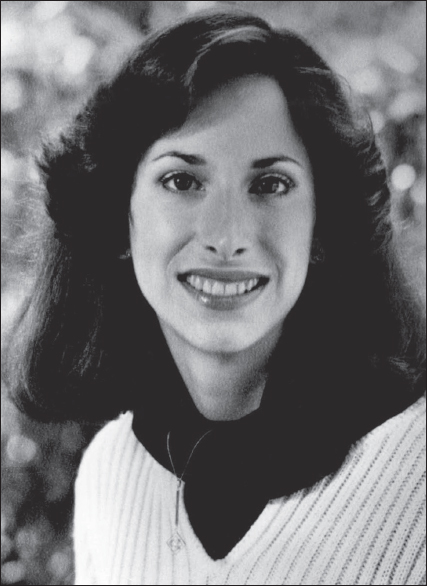

Margaret Bowman, age 21, was murdered by Ted Bundy in Florida in 1978. (photo credit: Associated Press)

Borrowing from Andrew “Ender” Wiggin, a fictional character in Orson Scott Card’s science fiction story

Ender’s Game

, psychopathic killers such as BTK believe that the power to cause pain, kill, and ultimately destroy is the only thing that matters because if you cannot kill, then you are at the mercy of those who can and nothing and no one will save you from them. In the mind of a psychopath such as BTK, torture and killing become the only means to achieve the feeling of domination and control that he craves above all else in life. In a similar expression of psychopathy, Ed Kemper the “Co-ed Killer” was quoted as saying, “It [killing] was an urge. . . . A strong urge, and the longer I let it go the stronger it got, to where I was taking risks to go out and kill people . . . risks that normally, according to my little rules of operation, I wouldn’t take because they could lead to arrest.”

Diagnosing and Treating Psychopathy

While the concept of psychopathy has been known for centuries, there has been considerable research attention paid to it in recent years. In particular, Dr. Robert Hare, a prominent researcher in the field of criminal psychology, has led research efforts to develop a series of assessment tools to evaluate the personality traits and behaviors attributable to psychopaths. Dr. Hare and his associates developed the Psychopathy Check List Revised (PCL-R) and its derivatives which provide a clinical assessment of the degree of psychopathy that an individual possesses.

41

Based on forty years of intensive empirical research, the PCL-R has been established as a powerful tool for the assessment of this serious and dangerous personality disorder. Specific scoring criteria rate twenty separate items on a three-point scale (0, 1, 2) to determine the extent to which they apply to a given individual.

The instruments developed by Dr. Hare and his colleagues attempt to measure a distinct cluster of personality traits and socially deviant behaviors which fall into four factors: interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and antisocial.

42

The

interpersonal

traits include glibness, superficial charm, grandiosity, pathological lying, and manipulation of others. The

affective

traits include a lack of remorse and/or guilt, shallow affect, lack of empathy, and failure to accept responsibility. The

lifestyle

behaviors include stimulation-seeking behavior, impulsivity, irresponsibility, parasitic orientation, and a lack of realistic life goals.

Antisocial

behaviors include poor behavioral controls, early childhood behavior problems, juvenile delinquency, probation violations, and committing a variety of criminal and deviant acts.

An individual who possesses all of the interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and antisocial personality traits measured by PCL-R is considered a psychopath. A clinical designation of psychopathy in the PCL-R test is based on a lifetime pattern of psychopathic behavior. The results to date suggest that psychopathy is a continuum ranging from those who possess all of the traits and score highly on them to those who also have the traits but score lower on them.

43

This PCL-R allows for a maximum overall score of forty. A minimum score of thirty is required in order to designate someone as a psychopath. The scores for those who are psychopaths vary greatly, revealing that very high to low levels of the condition exist among those who have it. Non-criminal psychopaths generally score in the lower range (close to thirty) while criminal psychopaths, especially rapists and murderers, tend to score in the highest range (close to forty). No two psychopaths score exactly the same on the test. The average non-psychopath will score around five or six on the PCL-R test.

Dr. Hare and other experts, including forensic psychologists and FBI profilers, consider psychopathy to be the most important forensic concept of the early twenty-first century. Because of its relevance to law enforcement, corrections, the courts, and related fields, the need to understand psychopathy cannot be overstated. This includes knowing how to identify psychopaths, the damage they can cause, and how to deal with them more effectively. For example, understanding the personality and behavioral traits of psychopaths allows authorities to design interviewing and interrogation strategies that are more likely to be effective when dealing with them. Psychopaths’ manipulative nature and skill in the art of deception can make it difficult for law

enforcement officers to obtain accurate information from them unless the interviewer has been trained in special techniques for questioning such individuals.

44

Professionals who work in the criminal justice system must understand psychopathy and its implications because they will definitely encounter psychopaths in their work.

Approximately one-third of all prison inmates who are considered to be “antisocial personality disordered” meet the criteria of severe psychopathy specified in the fifth edition of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(DSM-5).

45

For the very first time, the APA recognized psychopathy as a “specifier” of clinical antisocial personality disorder in the DSM-5, although psychopathy is still not an officially accepted clinical diagnosis. The recognition of psychopathy as a specifier of clinical ASPD by the APA follows nearly fifty years of research and debate. It is significant because the DSM-5 serves as a universal authority for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. The DSM-5 was published on May 18, 2013, superseding the DSM-IV-TR, which was published in 2000.

One important question remains to be asked: Can psychopathy be cured? According to mental health experts, the short answer to this question is no. Dr. Nigel Blackwood, a leading Forensic Psychiatrist at King’s College London, has stated that adult psychopaths can be treated but not cured.

46

Blackwood explains that psychopaths do not fear the pain of punishment and they are not bothered by social stigmatization. Psychopaths are indifferent to the expectations of society and reject its condemnation of their criminal behavior. According to Blackwood and others, callous and unemotional psychopaths simply do not respond to punishment the way that normal people do. Consequently, adult psychopaths in prison are much harder to reform or rehabilitate than other criminals with milder or no antisocial personality disorders.

47

Because they do not respond in a normal fashion to punishment, reward-based treatment seems to work best with psychopaths. Such strategies have been used effectively with psychopaths in institutional settings.

In reward-based treatment, psychopathic prisoners are given small privileges such as watching television or other perks in exchange for good behavior. For example, reward-based treatment has been utilized effectively with convicted serial killer Dennis Rader at the El Dorado Correctional Facility in Kansas. Rader has been a model prisoner since his incarceration in 2005. Although he remains in solitary confinement twenty-three hours per day, he has received increasing privileges,

including foods he likes, in exchange for his good behavior. He has told me that he looks forward to his little rewards. I believe that the obsessive personality of many psychopaths such as Rader make a reward-based system particularly effective. Their behavior remains good or even improves as they become increasingly fixated on their rewards. Despite the practical utility of reward-based treatments, however, the fact remains that there is no known cure for psychopathy. In other words, it can be managed quite effectively but not cured.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have examined two antisocial personality disorders—sociopathy and psychopathy—which have been linked by forensic psychologists to violence and serial murder. These two personality disorders are often mistaken for mental illnesses such as psychosis or schizophrenia by the public. Serial killers are rarely diagnosed with mental illness, however, and rarely found not guilty by reason of insanity in the court of law. We have determined that the traits of psychopathy are more highly correlated with the patterns of serial homicide, particularly organized serial murders, than are the traits of sociopathy. We have seen how psychopathic personality traits can be identified and measured by clinicians using the PCL-R test. Although reward-based treatments are used effectively to control psychopathy in institutional settings, there is still no known cure for it. In addition, the relationship between psychopathy and serial homicide is complicated and not absolute. That is, not all psychopaths become serial murderers and all not serial murderers are psychopaths, although there is a strong correlation between them. Serial murderers may possess some or many of the traits characteristic of psychopathy but this single disorder does not account for the full spectrum of serial homicide.

CHAPTER 5

THE MOTIVES, RITUALS, AND FANTASIES OF SERIAL KILLERS

Thus far is this book, we have defined serial homicide, discussed its prevalence in the US, debunked popular serial killer myths, and explained the contributions of criminal profiling and forensic psychology to our understanding of serial killers. We have also explored how certain antisocial personality disorders, particularly psychopathy and to a lesser extent sociopathy, are linked to serial murder, and we explored how antisocial personality traits can be predictive of specific predatory criminal behavior. As discussed, a chronic disregard for the laws of society and an inability to emotionally connect with others characterize psychopathic serial killers. However, psychopathy alone cannot fully explain the diverse patterns, rituals, motivations, and fantasies of serial killers.

This chapter is devoted to an in-depth exploration of the varied and complex motivations and ritualistic behaviors of serial killers. I’ll explain the diverse motivations of serial killers, including differences by gender. Also, I’ll compare and contrast the various categories and sub-types of serial killers such as thrill killers, hedonist lust killers, and power/control killers, which have been identified by the FBI and criminologists. In addition, I’ll present compelling case studies and important new insights into the varied motivations and lurid fantasy lives of serial killers. Expanding on chapters 3 and 4, this chapter also addresses the significant contributions of criminal profiling and clinical psychology to the identification and classification of serial killers.

The Secret Desires and Motivations of Serial Killers

As explained in chapter 3, tremendous attention has been paid to the psychological profiling of serial killers in recent decades by the news and entertainment media. The aspect of criminal profiling that seems to fascinate the general public the most is determining the motivations of serial killers. This is likely due to the fact that many people have a deep and compelling need to understand why someone would stalk and kill other human beings. The almost incomprehensible desires of serial killers elicit morbid fascination among the general population, social scientists, and even the law enforcers who hunt them.

In the criminal justice process, knowing the motivations of an unknown perpetrator helps detectives form a suspect pool in a serial murder investigation. Although the same approach is used to identify an unknown killer’s motivation in any homicide investigation, it is far more complicated in a serial homicide case. As mentioned previously, the majority of homicides are committed by someone the victim knows and, in many instances, knows well. The overall homicide pattern in the US reveals that more than two-thirds of all victims know their killer. In fact, many homicide victims, especially females, know their killer intimately. Such killings are considered crimes of passion due to the intimacy of the relationship between the victim and offender. Recognizing that most homicide victims do know their killer, detectives focus their attention on the relationships closest to the victim, particularly during the early stages of an investigation. This strategy is successful in leading detectives to the killer in the majority of homicide investigations.

48