Why We Love Serial Killers (9 page)

Read Why We Love Serial Killers Online

Authors: Scott Bonn

The FBI model of criminal profiling is known as criminal investigative analysis (CIA) and it is based on a premise that the personality of an unknown perpetrator can be predicted. More specifically, the “basic premise [of criminal profiling] is that behavior reflects personality,” said retired FBI special agent Gregg McCrary.

9

In a serial homicide case, according to McCrary, as reported by the APA

Monitor of Psychology

in 2004, FBI agents glean insights into criminal personality by answering questions about the murderer’s behavior at four different crime phases:

•

Antecedent

: What fantasy or plan, or perhaps both, did the murderer have in place before committing the act of murder? What triggered the murderer to act sometimes and not others?

•

Method and manner

: What type of victim or victims did the murderer select? What was the method and manner of murder—that is, shooting, stabbing, strangulation, poisoning or something else?

•

Body disposal

: Did the murder and body disposal take place all at one scene or multiple scenes? Was there an attempt to hide the bodies?

•

Post-offense behavior

: Is the murderer trying to inject himself/herself into the investigation by reacting to news media reports or contacting police investigators?

Six Steps in the FBI System of Criminal Investigative Analysis

The FBI system of criminal profiling involves a comprehensive six-step process. Each step is critical to the overall system, so the quality of input at each step directly influences the subsequent steps. Expanding on a discussion presented in the 2004 book

Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters

by Peter Vronsky, the six critical steps involved in the FBI profiling model are outlined below.

10

Step 1: Profiling Inputs

Step 1 involves the gathering and organizing of all relevant case information. This includes such items as a detailed report on the criminal investigation, crime scene photographs, a description of the neighborhood or area in which the murder occurred, the medical examiner’s report, a timeline of the victim’s movements immediately before death, and a detailed background profile of the victim.

Step 2: Constructing a Decision Process Model

In this step, the fundamental characteristics and details of the homicide are established. These include whether the killing was a serial or single murder, whether homicide was the primary objective of the killer or incidental to another crime, whether the victim was a high-risk individual such as a homeless person or a female sex worker versus a low-risk individual such as a professional, married man. Additional factors used in constructing the decision process model include whether the victim was killed at the scene of the attack or elsewhere and, if elsewhere, the characteristics of the scene where the murder might have occurred.

Step 3: Crime Assessment

Step 3 of the process is the most involved. In this step, profilers decide whether the crime scene has the characteristics of an organized offender, disorganized offender, or a mix of both. The breakthrough idea of classifying serial homicide crime scenes according to an organized/disorganized dichotomy is credited to the former FBI agent and profiler Roy Hazelwood. This concept was based primarily on the previously mentioned study of thirty-six serial predators conducted by FBI agents Douglas and Ressler. Profilers use a list of factors such as whether the victim’s body was positioned or posed by the killer, whether sexual acts were performed before or after death, and whether cannibalism or mutilation was practiced on the body. These factors are used to predict whether an unknown offender is an organized or disorganized killer. The organized/disorganized classification of offenders is the centerpiece of the FBI profiling approach and is explained below.

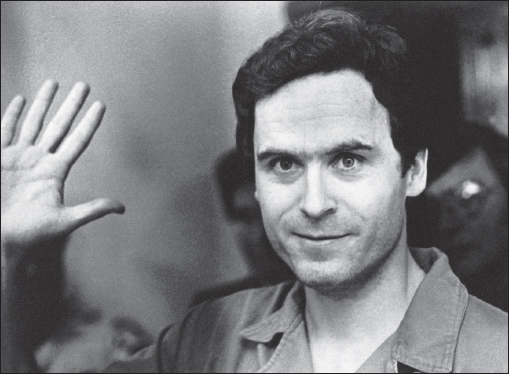

Ted Bundy mugs for the cameras after his indictment in Florida on July 28, 1978. (photo credit: Associated Press)

Organized Offenders

According to the offender and crime scene dichotomy, organized crimes are premeditated and carefully planned, so little evidence is normally found at the scene. Organized criminals, according to the classification scheme, are antisocial (often psychopathic) but know right from wrong, are not insane, and show no remorse. Based on historical patterns, organized killers are likely to be above average–average intelligence, attractive, married or living with a domestic partner, employed, educated, skilled, orderly, cunning, and controlled. They have some degree of social grace, may even be charming, and often talk and seduce their victims into being captured.

With organized offenders, there are typically three separate crime scenes: where the victim was approached by the killer, where the victim was killed, and where the victim’s body was disposed of. Organized killers are very difficult to apprehend because they go to inordinate lengths to cover their tracks and often are forensically savvy, meaning they are familiar with police investigation methods. They are likely to

follow the news media reports of their crimes and may even correspond with the news media. Ted Bundy, Joel Rifkin, and Dennis Rader are prime examples of organized killers.

Disorganized Offenders

Disorganized crimes, in contrast, are not planned, and the offenders typically leave evidence such as fingerprints or blood at the scene of the murder. There is often no attempt to move or otherwise conceal the corpse after the murder. Disorganized criminals may be young, under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or mentally ill. They often have deficient communication and social skills and may be below average in intelligence. The disorganized offender is likely to come from an unstable or dysfunctional family. Disorganized offenders often have been abused physically or sexually by relatives. They are often sexually inhibited, sexually uninformed, and may have sexual aversions or other pathologies. They are more likely than organized criminals to be compulsive masturbators. They are often isolated from others, live alone, and are frightened or confused during the commission of their murders. They often do not have reliable transportation, so they kill their victims closer to home than organized offenders.

Significantly, disorganized killers will often “blitz” their victims—that is, use sudden and overwhelming force to assault them. The victim’s body is usually left where the attack took place, and the killer makes no attempt to hide it. Jack the Ripper is the most classic example of the disorganized serial killer. The serial killer known as “Charlie Chop-Off” because of his penchant for genital dismemberment, is a more recent example of the mentally ill disorganized killer. Charlie randomly killed young boys in blitz attacks in New York City in the early 1970s.

It is also important to note that a serial murder case can also be a mix of organized and disorganized. This occasionally occurs, for example, when there are multiple offenders of different personality types involved in the killings. It can also occur when a lone offender is undergoing a psychological transformation throughout his killing career.

Modus Operandi and Signature

In addition to the organized/disorganized dichotomy, a serial killer may leave traces of one or both of the following behavioral characteristics: MO (

modus operandi

or method of operation) and

signature

—the personal mark or imprint of the offender. While every crime has an MO, not all crimes

have a signature. The MO is what the offender must do in order to commit the crime. That is, the MO is the means by which the perpetrator is able to commit murder. For example, the killer must have a means to control his victims at the crime scene such as tying them up. Significantly, the MO is a learned behavior that is subject to change. A serial killer will alter and refine his MO to accommodate new circumstances or to incorporate new skills and information. For example, instead of using rope to tie up a victim, the offender may learn that it is easier and more effective to bring handcuffs to the crime scene. The MO of Jack the Ripper, for example, was that he attacked prostitutes at night on the street with a knife.

The signature, on the other hand, is not required in order to commit the crime. Rather, it serves the emotional or psychological needs of the offender. That is, the signature is something the killer deeply desires or wants. The signature comes from within the psyche of the offender and it reflects a deep fantasy need that the killer has about his victims. Fantasies develop slowly, increase over time, and may begin with the torture of animals during childhood, for example, as they did with Dennis Rader. The essential core of the signature, when present, is that it is always the same because it emerges out of an offender’s fantasies that evolved long before killing his first victim. The signature may involve mutilation or dismemberment of the victim’s body. The signature of Jack the Ripper was the extensive hacking and mutilation of his victims’ bodies that characterized all of his murders.

Staging and Posing

As explained by Vronsky in

Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters

, the FBI profiler may also encounter deliberate alterations of the crime scene or the victim’s body position at the scene of the murder. If these alterations are made for the purpose of confusing or otherwise misleading criminal investigators, then they are called

staging

and they are considered to be part of the killer’s MO. Staging reflects a conscious and calculated choice on the part of the killer to confuse his or her pursuer. On the other hand, if the crime scene alterations only serve the fantasy needs of the offender, then they are considered part of the signature and they are referred to as

posing

. Thus, posing operates at the emotional level of the killer and reflects his or her secret desires. Sometimes, a victim’s body is posed to send a message to the police or public. For example, Jack the Ripper sometimes posed his victims’ nude bodies with their legs spread apart to shock onlookers and the police in Victorian England.

Step 4: Criminal Profile

In step 4 of the process, the FBI profiler produces a report for local investigators that predicts the possible personality, physical, and social characteristics of the unknown offender. The profile lists objects that might be in possession of the killer, such as pornography, and may propose strategies for identifying, apprehending, and even questioning the accused. An FBI profile can vary in length from a few paragraphs to a number of pages depending on how much information the FBI had to analyze at the input step.

Step 5: Investigation

In step 5 the local police department incorporates the criminal profile developed by the FBI into its own investigative strategy. Using the specific characteristics outlined in the FBI profile, local law enforcement authorities can narrow the list of suspects and implement strategies that are likely to lead to an arrest. If or when additional murders occur or additional information is discovered, the profile can be updated or expanded by the FBI during the investigation stage. The first high-profile case in which FBI profilers successfully assisted local authorities in a hunt for an unidentified serial killer was the Atlanta child murders in the early 1980s. FBI agents Douglas and Hazelwood were sent to Atlanta to work with local police and develop a profile in order to assist in the massive search for the killer.

Step 6: Apprehension

The final step of the FBI profiling process is apprehension. This is the accountability or proof-of-performance step. The accuracy of an FBI profile can be determined by matching its characteristics and details to those of the actual offender in custody. In the case of the Atlanta child murders, for example, the profile developed by FBI agents Douglas and Hazelwood proved to be extremely valid. When Wayne Williams was arrested in 1981, as predicted in the profile, he was a single young black male who owned a German shepherd, as well as a vehicle fitted with police lights that he used to impersonate a police officer and lure his young victims. The results of such successful investigations are added to the database in Quantico and the computerized algorithms used by the

profiling system are fine-tuned in order to increase profiling accuracy in the future.

How Accurate Is the FBI System of Criminal Investigative Analysis?

Over the past quarter-century, the BSU in Quantico has further developed the FBI’s profiling process, including a refinement of the organized/disorganized dichotomy into a more seamless continuum and the development of other serial predator classification schemes. However, despite the public notoriety afforded profiling as a result of the numerous books and Hollywood films that have focused on it in recent years, the FBI system is not without its critics. Contrary to popular mythology and as argued by Dr. Schlossberg, criminal profiling is not an exact science. As such, there have been numerous calls among criminal justice practitioners and researchers for unbiased, scientific testing of its validity and reliability.