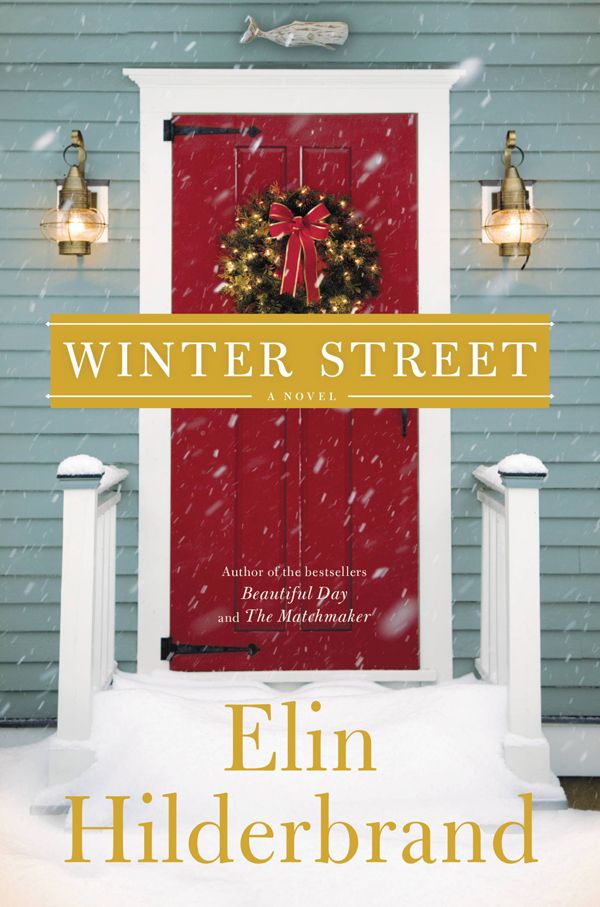

Winter Street

Authors: Elin Hilderbrand

Tags: #Fiction / Contemporary Women, #Fiction / Family Life

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For Judith and Duane Thurman, who have kept my paper angel ornament, as well as all of my other childhood memories, cherished and safe these many years.

Hugs and love.

H

e thinks nothing of walking into room 10 without knocking. The door is unlocked, and George hasn’t checked in yet, anyway. George is due on the eleven-thirty ferry with his 1931 Model A fire engine, a bespoke Santa Claus vehicle, but he was delayed because of snow in the western part of the state. George has gamely brought the fire engine over and donned the red suit every December for the past twelve years. George weighs in at 305 pounds, give or take the five, and is the jolly owner of a full head of white hair and a white goatee (new since his divorce; before, it was a full beard). Kelley wants George to arrive so that Mitzi will relax. According to Mitzi, no one can possibly replace George, and nothing ruins Christmas like an absent Santa.

When Kelley swings open the door to room 10, he realizes he’s intruding. There are two people in the room, kissing. Kelley’s first instinct—the instinct of everyone he knows when walking in on something private—is to blurt out

“Sorry!” and slam the door shut. (He has a quick, unfortunate vision of his aunt Cissy on the toilet during his grandfather’s wake.) But what he just caught the shortest glimpse of, the length of one frame of film, was nothing like his aunt Cissy on the john. It was two people in full, passionate lip lock—“necking,” they used to call it in high school. The click of the door instantly reveals the identity of those people.

It’s George, their Santa Claus, and Mitzi, Kelley’s wife.

Kelley flings the door back open, fast enough that George and Mitzi have yet to fully disengage. George still has his hands on Mitzi’s hips, and Mitzi’s hands are buried in George’s white hair.

“What…?” Kelley says. He’s not sure what to think. He has been in crisis for weeks. First of all, it’s December, a month he used to own on Nantucket. He had a full inn through Thanksgiving and Christmas Stroll, but he hasn’t had a paying guest since the tenth of December. Normally, he has a waiting list during the week of Christmas (just like the original Christmas: no room at the inn). The Drellwiches and the Kasperzacks used to come to see their grandchildren, the Elmers came to escape their grandchildren, and the other four rooms were taken by young couples who found Nantucket a charming place to spend the holiday—and then, of course, there was always George. But this year, nobody. This year, the neon sign in Kelley’s mind flashes:

VACANCY, VACANCY!

It’s his least favorite word in the English

language, especially since his finances are in such precarious shape. Kelley has kept the inn up and running for nineteen years by supplementing the inn’s budget with the treasure trove of savings he had when he left his “real” job, trading petroleum futures in New York. That treasure trove has now dwindled to an amount in the high four figures. Lately, Kelley has fantasized about selling the inn off as a private home—it would fetch between four and five million, he guesses—and moving to Hawaii. His ex-wife, Margaret, is flying to Maui on Christmas Eve, as soon as she finishes anchoring the CBS

Evening News.

When she told Kelley this a few weeks ago, he felt a category 5 pang of jealousy. He thought,

Please take me with you.

But the deeper reason Kelley has been addled is because his youngest son, Bart—who had been stationed in Vilseck, Germany, for two months, where it was all “pretzels and blondes”—was deployed to Sangin, Afghanistan, on December 19. He sent Kelley and Mitzi a text that said,

Made it in country. Love you.

And that was the last they heard. The texts that Kelley and Mitzi tried to send back were “undeliverable.” Kelley’s e-mails go through, but they remain unanswered. Kelley imagines his words whipping across sandy, inhospitable terrain.

Bart is the only child Kelley fathered with Mitzi, and he has been raised as a bit of a golden boy—favored, pampered, spoiled—or so the other three Quinn children would claim. Kelley thought the Marines would be the best choice

for Bart, but now that he’s gone, Kelley is racked with anxiety. And his anxiety is nothing compared with Mitzi’s. Mitzi has been a basket case.

Although she doesn’t appear to be worrying about Bart at the moment.

“Kelley,” she says, while tucking in her shirt. “Please.”

“Please?” he says. He’s genuinely confused.

“Give us a minute,” Mitzi says.

“Oh,” Kelley says. “Okay.” He closes the door, as if this were a reasonable request.

He hears their voices, but they are too faint for Kelley to make out a single word. The doors at the Winter Street Inn are all solid oak; when they were renovating, Kelley insisted on extra insulation in the walls. He never wanted to hear anything going on in any of the rooms. He would, however, like to hear the conversation between George and his wife right now.

At that moment, Isabelle comes bustling down the hall with a stack of fluffy white towels for room 10. They are Turkish cotton, replaced every year, one of the many reasons why Kelley is going broke.

Isabelle stops when she sees Kelley standing outside the door. She has worked at the inn for the past six months, and, although she has proven astute at reading Kelley’s moods and attitudes, apparently something about his posture now perplexes her.

“Qu’est-ce que c’est?”

she asks.

One of the reasons Kelley and Mitzi hired Isabelle was because they both decided they wanted to try to learn French, but half a year later, this is the only phrase Kelley understands.

What is it?

Or, literally,

What is it that it is?

There is no way to explain it in English, or French, or any other language. Kelley thinks,

I saw Mitzi kissing Santa Claus,

and he starts to laugh in a manic, unhinged way. Isabelle smiles uncertainly.

Kelley says, “George won’t be needing those towels.”

“Ah?” Isabelle says. “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” he says. “I’m sure.”

T

he dismissal bell rings, and chaos ensues—as bad as the last day of school, if not worse. Today, the kids are hopped up on sugar—hot chocolate, cookies, candy canes—and there is the allure of Santa Claus and presents, presents, presents! Also, there are coats to zip, and hats, scarves, and mittens to keep track of. Ava picks up two stray mittens between the auditorium and the school entrance. She drops them on the table outside the main office. Lost and found, to be dealt with “next year.”

Ava is hoarse, and her fingers ache. If she never plays “Jingle Bells” again, it will be too soon. It is, hands down, the least interesting carol ever written.

Why does everyone love it so?

She feels like Sisyphus with his boulder; she will have to play it

at least

one more time, at the annual Christmas Eve party at the inn. There will be no escaping that.

Still, there is something magical about the afternoon. The sky is sterling silver, the air shimmering with mist. It’s chilly but probably too warm for snow. Ava stands at the flagpole and waves to her students, who are waving madly back at her through the fogged-up windows of the school bus.

Merry Christmas, Miss Quinn, Merry Christmas, Merry ChristMAS!

How Ava longs to be eight again! Or, no, not eight but five. She was five years old the Christmas before her parents split.

Ava sees Claire Frye, wearing a long red coat and a matching red hat set precariously on top of her dark curls, run into her father’s arms. Her father, Gavin Frye, who looks like the pirate Bluebeard, picks Claire up and swings her around so that her hat sails through the air and hits the damp pavement. Gavin retrieves Claire’s hat and from his pocket pulls a wax paper bag that Ava knows has come from the Nantucket Bake Shop. Claire discovers two elaborately frosted sugar cookies inside—one Santa, one Rudolph. She chooses Santa and promptly eats his ear. Gavin munches Rudolph’s antlers and offers his daughter his arm, like a nineteenth-century gentleman caller.

Ava gets choked up. Claire’s mother was hit by a car in September; she died in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. This will be Claire and Gavin’s first Christmas without her. If

they

can get into the spirit of the holiday, well then, so can Ava. If she has to play “Jingle Bells” a hundred more times this season, she will do so in Claire Frye’s honor.

Ava doesn’t check her cell phone until she is sitting in the front seat of her red Jeep Wrangler with the engine running, the heater cranked, and her seat belt fastened. This is her pointless ritual; she wants to be ready for a collision with reality in the event that her phone doesn’t tell her what she wants to hear. Which, thanks to her crazy family and her maddeningly aloof boyfriend, it rarely does.

Deep breath. She presses the damn button.

A text from her mother, who tends to treat text messages like handwritten letters, down to the impeccable punctuation:

Hello, sweetheart! I’m in the car, headed to the studio. I miss you. Your paper angel is the only holiday decoration in my apartment. I’m off to Maui tomorrow; I’ll be staying at the Four Seasons. I’ll send you a ticket if you’d like to escape the winter wonderland…? Daddy sounded like even

HE

was tempted. (Mitzi must have bought a particularly ugly sweater this year—laughing out loud!) I love you, sweetie! Xoxo, Mom

Ava closes her eyes and envisions her mother’s three-bedroom apartment on the thirty-second floor of a luxury building on Central Park West—sumptuous and soulless.

Ava has no doubt that what her mother says is true; Margaret Quinn is far too busy to deal with Christmas decorations, except for the paper-angel ornament Ava made in second-grade Sunday school at Holy Trinity Episcopal, on East Eighty-Eighth Street, back when her parents were parenting and cared about things like religious education. Back when they lived in the happy, messy brownstone between York and East End. Margaret has saved the angel all these years in an uncharacteristic show of sentimentality. The angel would be dangling by fishing line in one of the floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the park, or it would be resting inside a six-thousand-dollar Dale Chihuly glass bowl on the ten-thousand-dollar coffee table carved from a single piece of teak harvested from an ancient southeast Asian forest.

Ava loves her mother and yearns for her even now, at age twenty-nine. Ava can see her mother on channel 3 every weeknight at six o’clock, but that’s hardly the same thing; in fact, it makes Ava’s longing worse, so she avoids watching the nightly news.

A text from Mitzi:

I’m so sorry.

Sorry for what? Ava wonders. But she deletes the message. She will have too much Mitzi as it is over the holiday break.

A text from her brother Kevin:

Stop by the Bar on your way home.

Tempting.

A text from her brother Patrick:

Something came up, Jen and kids headed west, I’m staying in the city for Christmas.

What? Ava reads the text twice, thinking there must be a mistake. She doesn’t care if she sees Patrick or not. As the firstborn, he tends to be bossy, bordering on dictatorial, and he’s egregiously mercenary—all he seems to care about anymore is money, money, money—but Ava can’t believe her nephews aren’t coming. What is Christmas without children? She nearly calls Patrick, but she knows he won’t answer while the stock exchange is still open.

Item 5: a missed call from her father (no message). Weird, because he knows she is unreachable until three o’clock, and if he needs her to pick up eggs or sugar or food coloring or bananas for the inn, he’d better speak to her in person, or she’ll conveniently tell him that she stopped by the Bar to see Kevin and never got the message.

Finally, she scrolls down to the name she has been hoping for. Nathaniel Oscar, labeled in her phone by his initials, NO. There are three text messages from NO, and Ava’s heart sinks. Three messages means bad news.

6 a.

Decided to head home after all, taking 1:30 flt, renting car.

6 b.

Hyannis. Going to Panera for chipotle ckn xtra mayo.

6 c.

Don’t be mad, Mom laid guilt trip. Back next wk, ill call. Xxx

“Arrraugh!” Ava starts to yell, but her voice is so strained from singing carols that she can barely get the sound out. She watches her favorite group of fifth-grade boys run for the ice rink, with their hockey skates slung over their

shoulders. She honks the horn at them, and they see her and wave.

Merry Christmas, Miss Quinn, Merry ChristMAS!

Liam tackles Joel, and Darian steals Jarrett’s hat. Not a one of them can carry a tune, and yet they talk incessantly about starting a rock band.

Ava adores them and hopes they grow up to be considerate boyfriends and thoughtful husbands.

Nathaniel is probably halfway to Greenwich by now. There are many things wrong with this scenario. Ava won’t be with Nathaniel for Christmas, he clearly won’t be proposing, the way she has hoped and prayed for every night (she prays to St. Jude, the patron saint of desperate causes), and he won’t provide an escape from the nuthouse that is the Winter Street Inn. He won’t be gamely singing along as she plays “Jingle Bells” for the ten zillionth time or handing out cups of Mitzi’s horrendous spiced cider (so heavy on the cloves, it’s nearly undrinkable). No… instead, he will be in the enormous stone house where he grew up, in Greenwich, Connecticut, with his parents, his two sisters, and their kids. He will be half a mile down the road from Kirsten Cabot, his high school girlfriend, who is recently divorced and home for the holidays.

Ava only knows this last piece of information because she accidentally stumbled across Nathaniel’s open Facebook page on his computer while he was in the shower a few days ago.

The message from Kirsten had read:

Please come home,

I need a shoulder to cry on. Budweiser cans in the backseat of your dad’s car like old times?

When Ava saw that, Nathaniel had yet to respond, but Ava knows now what decision he made.

Ava doesn’t

want

to love Nathaniel Oscar; she doesn’t

want

to want to marry him and give birth to five or ten of his progeny in rapid succession, but she can’t seem to help how she feels.

She considers herself a pretty together young woman. Teaching music at Nantucket Elementary School gives her enormous satisfaction. She loves her students and her classroom—the upright piano, tuned the first day of every month, the vintage turntable where she plays her classes the Beatles and Frank Sinatra. In the age of iTunes, Ava has realized, someone has to give the kids a musical education, someone has to teach them the classics. When she held up a vinyl copy of

Revolver,

borrowed from her father’s collection, not a single child knew what it was.

“It’s a

record,

” Ava said.

And they

still

didn’t know!

Ava also loves living at the inn; it’s not dissimilar from her dorm in college. She is a social bird and loves it when the inn is filled with guests. There is always someone new to talk to, always someone who wants Ava to play the piano so he or she can sing. Ava even likes living with her family—her brother Kevin, her brother Bart, and Kelley and Mitzi.

Bart is gone now, of course—to Afghanistan—which pains her.

Ava checks her phone again, wondering why there is still no word from Bart. She texted him four days ago. When he left for Germany, he promised he would always respond as soon as he could, and he always has, until Friday, when he deployed. Ava checks her e-mail—nothing.

Well, he’s at war now, so he’s busy—that’s probably not even the right way to describe it—and maybe there’s no cell service in Afghanistan?

Still, she sends another text. It says:

I miss you, Baby Butt. Please let me know you’re alive.

This text bounces back:

Undeliverable.

Ava wants to scream again. No one in her life is cooperating!

She rereads Nathaniel’s texts.

Chipotle ckn xtra mayo

is what the two of them order every time they go to Panera. Ava

introduced

Nathaniel to the chipotle chicken; it’s their sandwich, their chain restaurant, their tradition. One of the reasons Ava knows she’s in love with Nathaniel is that she loves doing regular, everyday things with him. She loves eating lunch at Panera in the crappy Hyannis strip mall with him; she loves waiting in line at the post office with him. She

loves

curling up in his arms on his brown corduroy sofa and watching holiday movies.

Trading Places

is their favorite. At least a dozen times in the past three weeks he has answered the phone by saying, “Looking good, Billy Ray!”

And she has answered, “

Feeling

good, Louis!”

In addition to being her lover, he is also her friend.

But now, it’s two days before Christmas, and he’s gone. “Eeeeeeearrgh!” Ava screams.

There’s a knock on her window, and she jumps. She wipes away the fog her breath is causing, and there stands Scott Skyler, the assistant principal, in just his shirt and tie—no winter coat. She cranks down her window.

“Hi, Scott,” she says.

“You okay?”

“Yes,” she says. “Not really. Nathaniel went home.”

“Oh boy,” Scott says. Scott has served as Ava’s confidant for the past twenty months, which isn’t really fair, as Scott harbors a crush on Ava that apparently only grows stronger the more she talks about Nathaniel.

“Want to go to the Bar?” she asks. A beer and a shot with Scott and her brother—maybe two shots, since, in addition to the Nathaniel problem, she misses Bart, and her mother, and there will be no adorable nephews to open the gifts she spent hundreds of dollars on—seems like the only thing in the world that will improve her mood.

“I can’t,” he says. “I’m serving dinner at Our Island Home tonight. Salisbury steak. You’re welcome to join me.”

Ava lets a single tear drip down her face. Even Scott is busy. He is a tireless do-gooder, something Ava loves about him. She tries to imagine any one of her three brothers serving Salisbury steak at Our Island Home and comes up empty.

“You’re coming over tomorrow night, though, right?” she says.

“Wouldn’t miss it,” Scott says, and he reaches over to catch the tear, a tender gesture that only starts Ava crying harder.

She wipes at her face with her palms and says, “Screw it, I’m going to get drunk.”

“Okay,” Scott says. “Maybe I’ll see you later.” He hurries back into the school, and Ava realizes that he only came out to the parking lot to check on her. Sweet, sweet man, great friend, but not her type. By which she means, not Nathaniel. She is sunk. Sunk!

She will go to the Bar.

Then her phone quacks and she thinks,

Nathaniel!

No such luck. It’s her father.

“What?” Ava barks into the phone. She loves her father, but he has the disadvantage of being constantly available and, because she still lives at the inn,

always around,

and hence he has to deal with her darker moods.

Kelley says nothing for a second, and Ava wonders if he’s going to reprimand her for being rude, or if he’s calling to tell her that Patrick has canceled, or if—God forbid—something has happened to Bart.

“Daddy?” Ava says.

“Mitzi left,” Kelley says. “She moved out.”