With Wings Like Eagles (18 page)

Read With Wings Like Eagles Online

Authors: Michael Korda

Tags: #History, #Europe, #England, #Military, #Aviation, #World War II

Though he was not normally an early riser,

Reichsmarschall

Göring himself, clutching his new baton, attended the beginning of operations at seven in the morning on the 12th, accompanied by field marshals Sperrle, the commander of

Luftflotte

3; and Kesselring, the commander of

Luftflotte

2, and surrounded by a glittering staff. Expectations were high.

August 12 would be a taste of things to come. The weather was fine; the Germans came in large numbers; and their strategy was well thought out, but largely thwarted by poor intelligence work, severe overoptimism, and faulty interpretation of reconnaissance. German bombers struck at Fighter Command coastal airfields like Manston, Hawkinge, and Lympne and dropped large numbers of bombs, but most of the airfields were back in service again by the next day, although the

Luftwaffe

wrote them off as “destroyed.” Certainly, a great deal of damage was done, but for the most part it was nothing that couldn’t be put right with shovels and a bulldozer—and of course a great many of the bombs fell in the surrounding fields, where they did no harm except to the crops of nearby farmers. The concentrated attack against the radar stations should have paid off, but the dive-bombers aimed at the tall radar towers, which looked fragile but were almost impossible to hit from the air, instead of concentrating on the more vulnerable underground operation centers and the plotting huts, without which the radar masts were useless. In most cases the radar stations continued to function, and Dowding’s decision to use young women from the WAAF as radar plotters was justified—without exception, they showed amazing courage and coolness, and continued to work even when under direct attack. The day proved, even to doubters, that the young airwomen could take it as well as men, and also saw the first casualties among the WAAFs.

Dowding’s foresight in burying the connecting telephone lines from the radar stations to the group and command filtering rooms deep underground and shielding them in concrete, a decision about which the members of the Air Council had been so skeptical, also turned out to have been money well spent. At the end of the day the Germans claimed to have destroyed seventy British fighters, whereas in fact the British lost twenty-two aircraft and the Germans thirty-one. Only one radar station was put out of action, and none of the forward fighter airfields was put out of action for long, although the Germans assumed they had been. The 12th ended on a bizarre note with a German night attack on Stratford-upon-Avon, birthplace of William Shakespeare, and then as now a quaint tourist town, of no strategic importance to Fighter Command. The day that had been intended to maul Dowding’s fighters in anticipation of Eagle Day and destroy Fighter Command’s “eyes and ears,” its radar stations, for tomorrow’s big attack, had done nothing of the sort, although the

Luftwaffe

high command was convinced that it had, and that Fighter Command was already on the ropes. One can understand why, of course—if you started with the assumption that RAF Fighter Command might have as few as 300 fighters left, then went on to assume that you had destroyed seventy of them, as well as putting the coastal airfields and two of the radar stations permanently out of action, then the day would seem to have been a promising, perhaps even a triumphant overture to the big attack. But, as it happened, this was not the truth.

Seen from the British side, however, the day seemed worse than it had in fact been. The attacks on the radar stations, although not particularly successful, seemed to demonstrate that the Germans understood the vital importance of knocking them out, and would concentrate on them from now on; and although the attacks on the forward airfields had been ineffective, they had nevertheless done a great deal of damage, and showed that the Germans had the right idea. A sustained and increasingly well directed bombing campaign, concentrated on the radar sites and his airfields, was what Dowding feared most.

Indeed, the day was serious enough that Dowding might have supposed that the 12th was the opening of the big

Luftwaffe

attack he was expecting, if he had not been tipped off by Churchill that it was planned for the next day. Although Dowding was not yet on the select list of recipients of “Ultra” information,

*

thanks to the Poles the code breakers at Betchley had already deciphered the mysteries of the German armed forces’ Enigma ciphering machine, and were able to read the flow of orders from Berlin to

Luftflotten

2 and 3, including Göring’s grandiloquent order of the day:

REICHSMARSCHALL GÖRING TO ALL UNITS: ADLERANGRIFF! YOU WILL PROCEED TO SMASH THE BRITISH AIR FORCE OUT OF THE SKY. HEIL HITLER!

8

I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm.

—Elizabeth I, speech at Tilbury, August

18, 1588

You must consider that no wars may be made without danger.

—Sir Roger Williams, in a letter to the Earl of Leicester, from the besieged town of Sluys, August

1588

*

D

espite all the modern technology at the disposal of the

Luftwaffe

—and although it consistently underestimated the importance of British radar, it had, as would shortly become apparent, a few tricks of its own up its sleeve—it was in one respect no better off than the duke of Medina Sidonia was as he led the Spanish Armada, 130 great ships in all, past The Lizard, the first landfall in Cornwall, into the English Channel on July 29, 1588. The weather would still determine the success or failure of the attack, in a part of Europe where bad weather was notoriously common.

Philip II’s ambitious plan for the conquest of England had been that Medina Sidonia should sweep through the Channel with his immense fleet, destroying the English fleet on the way, then meet with the duke of Parma—Europe’s most formidable soldier—off the ports of the Spanish Netherlands, and help ferry his army across to England in flatboats, to restore the Catholic faith. The Spanish Armada was defeated in part by the smaller and more nimble ships of the English and by the superior seamanship of the English captains in their own familiar waters, but the weather also played a large role. The duke required a good steady wind from the southwest, clear weather, and calm seas for the final stage of his campaign, but none of these was consistently forthcoming. Tacking about in rough seas, with patches of fog, many of his ships became separated from each other in the treacherous waters of the Channel, with its hidden rocks, shoals, currents, and sandbars, and its enormous tides, and fell prey to the English before the “invincible” Armada was anywhere near its goal.

Now, 352 years later, Göring faced a similar problem. He required a protracted period of good weather to bomb southern England on a scale sufficient to destroy Fighter Command’s airfields, and the factories in which Hurricanes, Spitfires, and the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine they both used were produced. Every day of fine weather was to the Germans’ advantage. On the other hand, every day of rain, fog, or low cloud cover was an advantage to Fighter Command, since it gave Dowding’s fighter squadrons a chance to rest, repair damaged facilities, and service their aircraft. We know everything about the weather in 1588—it was such an important factor that on both sides, every captain noted it in his logbook, with every change of wind and course. Likewise, in every detailed, day-by-day account of the Battle of Britain the description of the events of each day begins with the weather for that date. For the airmen, as for the sailors of the sixteenth century, weather was the single most important (and least predictable) element of the battle. Of course meteorology had improved substantially since the duke of Medina Sidonia’s time, but it was still by no means an exact science, and failure to get it right could still have serious consequences.

As if to demonstrate this,

Adler Tag

, the opening day of

Adlerangriff

, was a fiasco. Intended as a giant blow with the full strength of

Luftflotten

2 and 3, it got off to a muddled and disastrous start. The RAF described the weather for the day as “Mainly fair…early morning mist and slight drizzle in some places and some cloud in Channel.” Perhaps only a British meteorologist would describe mist, drizzle, and cloud as “mainly fair”; in any case, the German meteorologists felt, on the contrary, that the weather forecast was bad enough to call for the delay of

Adler Tag

, and Göring, with whatever impatience, agreed, and ordered the attack postponed until the afternoon, when the weather was supposed to improve. Unfortunately, his signal canceling the morning attack did not arrive in time to stop some of his units, which had already taken off at dawn—a perfect example of the wisdom of Napoleon’s famous remark, “

Ordre, contreordre—désordre

,” and of Göring’s amateurish and self-indulgent behavior as a commander. It is not clear whether the signal failed to reach the German units that went on with the attack or whether they were simply determined to “press on regardless,” to use the popular British military phrase for attacking despite an order to stay put or against insurmountable difficulties; but for whatever reason

Kampfgeschwader

(KG) 2,

*

with seventy-four Dornier 17 bombers under the command of Colonel Johannes Fink, a tough-minded, competent veteran aviator of World War I, went on even after the signal was relayed to it and many of its fighter escorts had turned back, some of the fighters because they had received the signal, others because they couldn’t find the bombers they were supposed to accompany in the clouds. Either way, it was exactly the kind of military muddle Napoleon had warned against.

The plans for

Adler Tag

had been drawn up with exemplary German precision, with exact times and courses for every unit involved—nothing was left to chance, and everything was spelled out in detail. It was a military masterpiece, intended to totally eliminate muddle, but it did not take into account human error (such as Göring’s impulsive decision to postpone the attack at the last minute, or the fact that some of the bombing force was equipped with radio crystals of a different frequency from those in the fighters, thus making it impossible for their fighter escorts to communicate with them, and vice versa), or the difficulty of unforeseen weather.

A further problem, which would emerge during the course of the day, was that however sophisticated the plan might be, it was based on poor intelligence. Colonel Josef “Beppo” Schmidt, the

Luftwaffe

’s chief of intelligence, seems to have been better at telling his boss what he wanted to hear than at providing useful targeting information. The purpose, after all, was to deliver a knockout blow to Fighter Command. There was no deliberate intention here of bombing civilian targets, or of sowing terror among civilians, so the situation was unlike the bombing of Warsaw and Rotterdam, or the “Blitz” against major British cities later that autumn, or for that matter the massive “area bombing” of major German cities by RAF Bomber Command from 1942 to the end of the war—and the Germans’ targets were carefully calculated with the objective in mind.

Given that objective, it is all the more surprising that the plan called for so many widespread attacks on targets that were unlikely to hurt Fighter Command. It was not as if the British had made any serious attempt to hide or keep secret the location of Fighter Command’s airfields, still less the factories in which the fighters were built, or Fighter Command Headquarters, or the vital radar towers, some of which were clearly visible in good weather from across the Channel with binoculars. Much of the information the Germans required was easily available before the war in guidebooks; in the British government’s excellent, detailed Ordnance Survey maps, which could be bought at any bookstore; in news stories; or even from the local telephone directory. Had the German air attaché in London cared to spend his holidays before the war driving around southern England with a few Ordnance Survey maps in the glove compartment of his car, and a Shell Motorist’s Guide and a pair of binoculars appropriate for bird-watching on the seat beside him he could easily have picked out most of the vital targets of Fighter Command—it did not require the services of a master spy, nor did the Germans have one in Britain. (One of the Japanese military attachés provided Tokyo with a more accurate view of Fighter Command’s strength by taking up golf and playing regularly at golf courses close to RAF fighter airfields.) It would be symptomatic of the whole day that although 120 Ju 88 bombers of

Lehrgeschwader

, or LG, 1 (the

Lehrgeschwader

were elite “demonstration” units formed around a nucleus of experienced instructors) spent nearly an hour bombing Southampton in the afternoon, they merely destroyed the Raleigh Bicycle factory, Pickford’s furniture storage warehouse, and a refrigerated meat storage depot, leaving untouched the Vickers-Supermarine factory in which Spitfires were produced. (A second, larger “shadow” factory had been completed at Castle Bromwich, near Birmingham, but production difficulties caused largely by the fact that it was under the control of the imperious Lord Nuffield, the automobile manufacturer, who was at odds with Lord Beaverbrook, meant that the Southampton factory was still the primary producer of the aircraft in 1940.)

*

There was nothing at all secret about the Spitfire factory at Woolston—it was large, easy to find, marked clearly on city maps, and listed in the Southampton telephone directory—and at least in theory one would have thought LG 1 worth sacrificing if necessary to destroy it.

Colonel Fink—whose aircraft had bombed a Coastal Command rather than a Fighter Command airfield, another result of faulty intelligence from Beppo Schmidt’s staff—had not been alone in failing to receive the recall message.

Kampfgeschwader

54 attacked the RAF airfields at Odiham and Farnborough, neither of which was a Fighter Command airfield; and a substantial force of Bf 110 twin-engine fighters that had flown out to support the KG 54 bombers failed to find them in the clouds, made a landfall just west of the seaside resort town of Bournemouth about fifty miles away from KG 54 as the crow flies, and got bounced by British fighters for their pains. By mid-morning those Germans who had failed to receive (or ignored) the recall were back at their bases, having accomplished nothing of value and complaining bitterly—Fink the most loudly of all—about the absence of fighter support and the fact that whatever radio device the British were using to detect German aircraft, it was still working all too well, despite claims that the whole system had been put out of action the day before. Fink had lost five bombers, and had many more damaged; KG 54 had lost four aircraft; and the Bf 110s of

Zerstörergeschwader

(ZG) 2 had lost one fighter. Despite the iffy weather and poor visibility of the morning, Air Marshal Park’s RAF fighter squadrons had apparently experienced no difficulty at all in finding the German raiders—a fact that struck Fink and many others (but apparently not Beppo Schmidt) as deeply disturbing and worthy of further investigation. (It is notable that although Fink was upset by KG 2’s losses, they were in fact substantially below 5 percent, which RAF Bomber Command deemed an “acceptable” rate of loss for operations.)

Clearly, Fink, like many in the

Luftwaffe

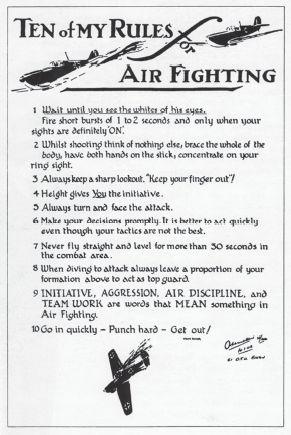

, assumed that the raids on the 12th had severely damaged Fighter Command’s power to resist, and was startled by the number of British fighters that nevertheless appeared, and the apparent ease with which they found him. As it happened, Fink also had the bad luck to be attacked by Flight Lieutenant Adolph “Sailor” Malan of No. 74 Squadron, a burly South African who would prove to be one of the most determined, successful, and intelligent RAF aces of the Battle of Britain. (Malan was the author of “Ten of My Rules for Air Fighting,” which was printed as a poster for display at fighter airfield dispersal huts. The first rule was

“Wait until you see the whites of his eyes!”

*

) Fink had also been attacked by one of the only two Hurricanes in Fighter Command armed with twenty-millimeter cannon instead of machine guns, flown by Flight Lieutenant Roddick Lee Smith of No. 151 Squadron. Smith was a convert to cannon. Despite the fact that the heavier guns and their bulky ammunition drums reduced the Hurricane’s speed and maneuverability, he believed that they “packed a much greater punch and at a longer range,” and managed to demonstrate it convincingly.

The morning, however chaotic, should have been a warning to the Germans that Fighter Command had

not

been seriously inconvenienced by the ambitious operations of the previous day, and should also have given them a clue that Dowding’s elaborate, carefully thought out system of radar and centralized fighter control was the key to the battle. German signals intelligence reported that all the radar stations were back in service—the British were sending out a dummy signal to conceal the fact that the Ventnor station on the Isle of Wight was still under repair—but this news does not seem to have interested anyone in the

Luftwaffe

high command, perhaps because Field Marshal Kesselring now had an angry

Reichsmarschall

Göring (and Göring’s sumptuous private train,

Asia

) on his hands at his headquarters, as well as an even angrier Fink to deal with.

Kesselring managed to shake off Göring and his entourage long enough to fly to Arras and calm Fink down, and by noon the weather had improved, as promised. The sky cleared, the sun came out, and it was decided to proceed with

Adler Tag

late in the afternoon as if nothing had happened.

If numbers alone could do the trick, the

Luftwaffe

had certainly amassed an impressive force—a combined force of 197 Ju 87s and Ju 88s would attack the Southampton area, with heavy fighter protection, while farther east large numbers of Ju 87s, escorted by fighters, would cross the Channel between Calais and Boulogne to attack the Short aircraft factory at Rochester, in Kent, and the airfield at RAF Detling, near Maidstone. Once again, however, German intelligence seems to have been misinformed. Although the Germans missed the Vickers-Supermarine factory in Southampton, the Short aircraft factory in Rochester took a pasting (the RAF slang of the day for receiving a heavy attack), but it manufactured bombers, not fighters; nor did Fighter Command use RAF Detling, which was yet another Coastal Command airfield. The airfield at RAF Andover was also attacked in error—the Stuka dive-bombers mistook it for the more important Fighter Command airfield at Middle Wallop. More damage was done to a nearby golf course than to the runway, but the officers’ mess was destroyed by a direct hit. A late-night attack by a small number of He 111s on the Nuffield Aero Works, near Birmingham, did “considerable” damage—and ought to have caused somebody in the RAF to ask how the

Luftwaffe

could achieve such accuracy at night—but the damage was nothing that couldn’t be quickly put right. In the words of the RAF report for the day, “Enemy aircraft activity over this country has been on a scale far in excess of anything hitherto carried out,” but at the end of the day the amount of damage actually inflicted was neither crucial nor impressive. All told, twelve RAF personnel were killed, and twenty-three civilians. The Germans lost thirty-eight aircraft; the British lost thirteen fighters, plus ten bombers destroyed on the ground. Only three British fighter pilots were killed in action.

*